3D: Stereoscopy for Dummies

3D: Stereoscopy for Dummies

This post originally appeared in French on the ONF.ca blog.

***

Marc Bertrand, a producer at the NFB’s Animation and Youth Studio, gave two master workshops on stereoscopy, also called 3D imaging, on March 8, 2013 at the Phi Centre during the Montreal International Children’s Film Festival (FIFEM).

Marc has produced 6 animated films in 3D during his 15 years at the NFB. He gave an overview of the experience he has gained to explain the principles of stereoscopy – a technology that has changed dramatically over time. “Ten years ago [stereoscopy] was expensive and complicated,” Marc said.

Fortunately, that’s no longer the case. Filmmakers can now understand stereoscopy and use it in their films without having to invest millions of dollars in the process.

Stereoscopy 101

In order to understand the principle of 3D imaging, you have to understand human vision. The reason we have two eyes is so that we can see things around us in three dimensions. That’s why we need to wear glasses when watching a 3D film: everything depends on vision. Our left and right eyes don’t see the same thing. That becomes readily apparent if we close one eye at a time. The image in front of us shifts from one eye to the other. As Marc explained,

“Our brain is able to merge the two images into one so that we have a single stereoscopic vision. If we didn’t have that ability, the world we see would be completely different… and flat.”

The principle of stereoscopy was invented in the 1850s. It was already understood at that time that two cameras were needed, placed side by side at a distance equivalent to the space between both eyes to produce a stereoscopic effect. The two images are then projected onto a screen. The 3D glasses enable our brain to perceive a single, three dimensional image.

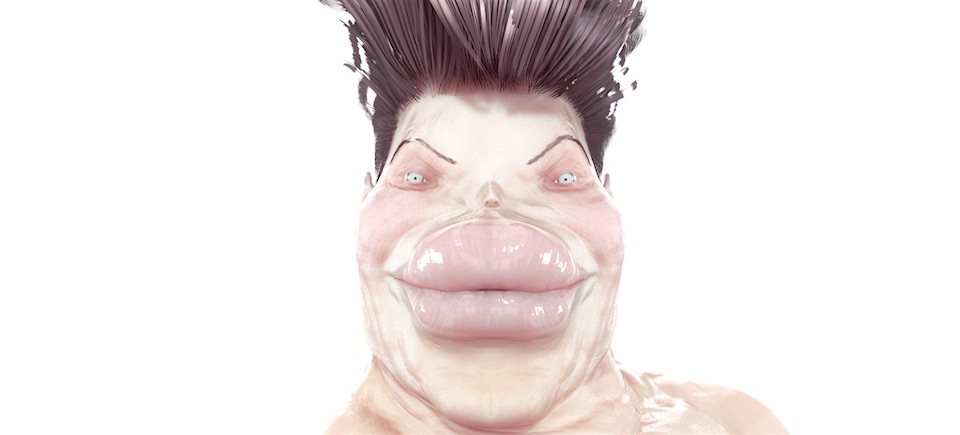

3D glasses

There are several different types of 3D glasses: two-colour glasses (the most common), which result in an anaglyphic image, passive glasses with polarized lenses and active 3D glasses (as seen in the photo of Marc, above). Active glasses are synchronized with the screen and block the image six times (alternating three times per eye) for each of the 24 images projected per second. As a result, the brain registers the images that each eye sees within the span of a second and turns them into single images. “The choice of glasses is very important for image quality,” explained Marc. He prefers active glasses.