NFB Pause: Alanis Obomsawin Back On Stage

NFB Pause: Alanis Obomsawin Back On Stage

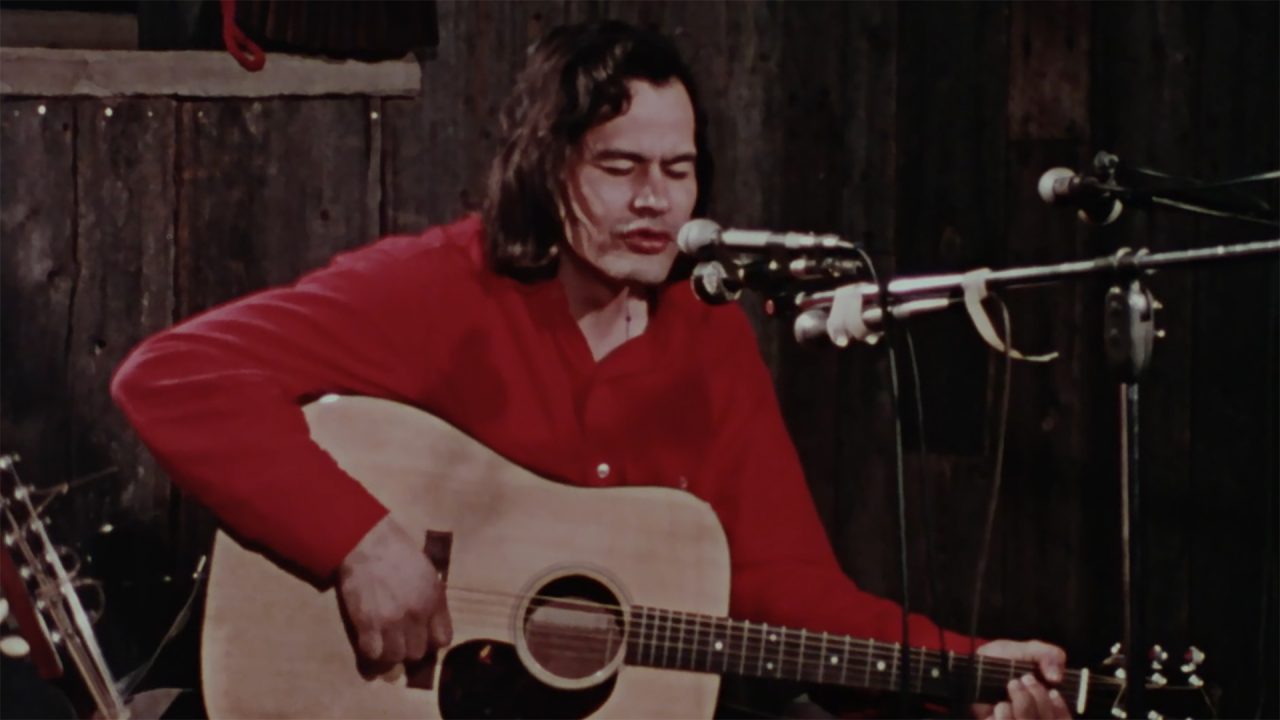

Utrecht, Holland, November 12, 2017. Food is piled high on the table of a local bar. Sitting around it, a group of Montrealers pinch themselves, wondering if they’ve really just watched a musical performance by 85-year-old Alanis Obomsawin—more than 30 years after the last time she stepped onto the stage.

Between bites, Obomsawin is probably pinching herself and wondering if it was real too. She’s made 50 films during her half century with the NFB, and been granted honorary doctorates and international awards, but she still had stage fright earlier this evening before walking out under the lights at the enormous, multi-stage TivoliVredenburg music complex.

It’s 2 a.m. on the last night of the Le Guess Who? festival, which just closed out with Obomsawin’s show, in which she performed in its entirety one of her lesser-known albums, Bush Lady (1988), accompanied by a quartet of local musicians and Montrealer Radwan Ghazi Moumneh.

Twelve months ago, this performance would have been highly unexpected. But Moumneh, the show’s musical director, is quick to say that the unexpected very quickly turned into “a highly anticipated performance.” A standing ovation from the full house testified to that.

Three bar-filled streets over, at the heart of the medieval city of Utrecht’s downtown core, stands the Louis Hartlooper Complex, an art deco theatre that screened Obomsawin’s 1984 film Incident at Restigouche the previous afternoon. The film was chosen by Frédéric Savard, a 34-year-old NFB colleague and music lover who is behind the Bush Lady revival and who has travelled to Europe with Obomsawin. “I think many people will be shocked by the film,” she said a few days earlier, during an interview in her hotel room.

The documentary, which takes place in 1981, is about police brutality in Restigouche County after the passage of new salmon-fishing regulations. Events escalated to the point where 550 provincial police raided a Mi’kmaq reservation with a population of 150 Indigenous fishermen and their families.

It was a natural subject for Obomsawin, a filmmaker who has made it her mission to educate people on Indigenous perspectives. Even if that mission has at times meant fighting tooth and nail—as an Indigenous person and as a woman—to get her ideas across in the all-too-macho film world.

In the film, we see Obomsawin dramatically reproaching the provincial fisheries minister of the day, Lucien Lessard, during a memorable interview.

Incident at Restigouche is a classic in the Abenaki filmmaker’s long career, which has included iconic titles such as Rocks at Whiskey Trench and Kanehsatake: 270 Years of Resistance.

Speaking out

The tenacity Alanis Obomsawin has shown throughout her long film career has parallels in the voices of Indigenous North American authors, whose books arose in part from an urgent need to be heard and to educate Indigenous and non-Indigenous people about their history. These books include the shocking, autobiographical Je suis une maudite sauvagesse (I Am a Damn Savage) by Innu writer An Antane Kapesh, published in 1976 by Leméac. As researcher Maurizio Gatti puts it in Être écrivain amérindien au Québec (Being an Indigenous Writer in Quebec), published in 2006 by Hurtubise:

When the federal government brought in the 1969 White Paper recommending the abolition of Indian status and the final assimilation of Indigenous people into the Canadian population, Indigenous people turned to a written language that was not theirs, but that allowed them to reach a large number of distant people to express their refusal to assimilate and their commitment to preserving their particular cultures.

Despite all her success, Obomsawin sees her journey not as a career, but as a mission. On the first day of the festival, in her room at the Grand Karel V (a 1990s squat turned chic hotel, where the festival’s big names, including former members of Sonic Youth, Sun Kil Moon, Keiji Haino and others are staying), Obomsawin tells me that what interests her most is change:

We are finally seeing significant changes. We’re living in a different time, and I saw that with my latest film [Our People Will Be Healed, the fourth in a cycle of five films about the rights of Indigenous children]. I am lucky enough to have lived this long, so I could witness the big changes happening now.

Arrival at the NFB

Alanis Obomsawin arrived at the NFB in 1967, brought in as a consultant by producers Joe Koenig and Bob Verrall, who had seen her in a TV report by director Ron Kelly, who was then working for the CBC. Obomsawin has said she new nothing about filmmaking at the time:

It was a great school for me. What was great about the NFB of that era is that all the directors and producers there were on staff. We had a lab, a camera department, sound department, and so on. If there was anything I wanted to learn, anything I didn’t understand, someone was there to help me. It was wonderful. Bob Verrall gave me a lot of support. And in that era—the early 1970s—John Grierson had come back to Montreal and I became friends with him. He encouraged me a lot and taught me all kinds of things I would not have otherwise known.

Although she started off as a young activist known for her singing talent—seen with great pomp during a 1960 concert organized by the legendary Folkways label at Town Hall in New York, which she dedicated to the community of Odanak, where she grew up until age nine—Obomsawin would go on to a highly productive career at the NFB. It began with film strips for classrooms:

A filmstrip is like a strip of 35-mm film which passes through a small projector. To “create” the story, you would refer to numbers on a slide, which corresponded to a track on an LP. Later, we used cassettes. Every class had one of these special projectors, with a turntable and slides. It was really the first time that we had a project “made by us” [Indigenous people] for classrooms.

Her first film, Christmas at Moose Factory, is a portrait of life over the holidays in the James Bay Cree community of Moose Factory, as told through children’s drawings and narrated by a young girl, all set to music by Arthur Cheechoo, Sinclair Cheechoo, and Jane Cheechoo.

Many of the hallmarks of Obomsawin’s work can already be seen in this film, including the importance of children, the primacy of speech accompanying visuals, the recounting of the events of daily life by those who live it, and the foregrounding of Indigenous talents who are little-known outside their communities.

Obomsawin would further delve into these subjects in many of her films, notably Richard Cardinal: Cry from a Diary of a Métis Child and Our Nationhood, as well as through her own activism in cultural politics. As a member of the Mariposa Folk Festival Board in the 1970s, she would ensure invitations were extended to Indigenous performers. Several of these artists have enjoyed a revival over the last few years, in large part thanks to the work of DJ Kevin Howes and the Light in the Attic label, which released the Native North America compilation in 2015.

I knew all those artists. Willie Dunn was very well-known. [In 1972 Dunn would co-direct The Other Side of the Ledger with Martin Defalco and write the music for Defalco’s 1975 feature, Cold Journey.] I remember how extraordinary Mariposa was, Obomsawin says. One year, Estelle Klein [the festival’s artistic director], said to me “You know Alanis, we’re gong to have a mouth harp workshop, and I was wondering if you’ve got anyone.” I said yes, one of my guests is a very elderly Inuit woman who plays.” She said, “Do you think we could put her in with our performers?” It was phenomenal. As soon as she started to play, the atmosphere changed completely. It was like we were in the Arctic—the sound of the birds and everything. People started to shout. We had a marvellous audience, thousands of people listening to her. She’s in my film Amisk [1977].

Kway kway, good evening, bonsoir tout le monde

It’s 2:30 a.m. Plates have been emptied, glasses drained, and Obomsawin is exhausted. Anyone who knows her knows that she is a sparkplug. Exhaustion does not come often. As the evening draws to a close, those of us still here gather around her. Our plane leaves tomorrow in the early afternoon.

A sentence I heard earlier has been swirling around in my mind. It perfectly captures the career of a woman who started off touring schools, residential schools, and prisons, to visit, in her words, “her relatives” (who made up—and continued to make up—an absurdly high proportion of those incarcerated): “I never tried to lean on guilt or call anyone a liar. Instead, I insisted on another version of history.”

That may just be what she succeeded in doing tonight, opening her performance with a trilingual greeting. “Kway kway, good evening, bonsoir tout le monde.” In her introduction she explained that the territory of the Wabanaki people once covered all of New England, the Maritimes, and parts of Quebec. Then, the English, the French, and the Dutch arrived.

This brings to mind one of the key themes running through her films: relearning and reclaiming a sense of pride requires the efforts of guides who see the critical importance of human dignity. Obomsawin is one of these people.

Nice article.