70 Years of Animation, Part 2 – Norman McLaren

70 Years of Animation, Part 2 – Norman McLaren

*This post is a translation from French. You can see the original post here.

In Part One, I mentioned that while the NFB initially lacked an animation department, by signing a co-production agreement with the Disney studio and buying films by Philip Ragan, an American animator living in Philadelphia, it was able to start producing animated films beginning in 1941. Thanks to these agreements, the NFB also distributed films promoting the sale of Victory War Bonds, thereby fulfilling its commitment to the National War Finance Committee, a government body responsible for conducting advertising campaigns. John Grierson, however, had other ideas: he saw this as a stop-gap solution. He wanted to attract an extremely talented animation filmmaker, whom he had discovered several years earlier, to create an animation studio at the NFB.

The filmmaker—the ace that Grierson had kept hidden up his proverbial sleeve—was none other than Norman McLaren. Born in Stirling, Scotland, in 1914, he began to study interior design in 1932, at his father’s alma mater, the Glasgow School of Art, where he developed a passion for film, music and painting. Upon seeing Oskar Fischinger’s abstract animated film Studie Nr. 7, set to Brahms’ Hungarian Dance No. 5, he knew he had found his calling. He made his first animated film without a camera, using ink to draw directly on a 35mm film, patiently scraping off its emulsion. He showed his film to a number of people, but because the projector was so old, the film sustained serious damage over time and was rapidly destroyed. It is lost to us forever. McLaren, however, did not give up. He got hold of a 16mm camera and made two films: 7 till 5 and Camera Makes Whoopie. Subsequently, he went back to drawing on film with Color Cocktail, which garnered a prize at the Scottish Amateur Film Festival, bestowed by none other than . . . John Grierson. The future commissioner of the NFB instantly recognized McLaren’s talent and invited him to work at the General Post Office (GPO) Film Unit in London. McLaren accepted and worked there from 1936 to 1939. These were his formative years, spent making documentaries and animated films. Later he would say that at the GPO he learned discipline, something he stated was lacking in his early films.

Just before joining the GPO Film Unit, McLaren did a stint as cameraman on Defence of Madrid, Ivor Montagu’s documentary on the Spanish Civil War. The things he saw during the making of this film shook him to the core and had a decisive influence on his career. In 1939, he felt war was imminent in Europe and thus decided to emigrate to the United States, not wanting to relive the kind of carnage he had seen in Spain. Without knowing it, he was approaching the place that would become the site of his future life and career—Canada. McLaren settled in New York in 1939, working as an independent filmmaker for two years. In 1941, Grierson travelled to New York to ask McLaren to come and work for the NFB, reassuring him that he would have complete artistic freedom. McLaren hesitated. He believed that he had already made commitments that were not easily broken. Grierson, however, promised to convince the producers who had hired McLaren to allow him to leave. It seems that Grierson was, in fact, very persuasive, since McLaren arrived in Ottawa in September 1941. Later, McLaren would state that to convince the New Yorkers, Grierson had invoked the War Measures Act and the need to repatriate British citizens.

As soon as McLaren arrived, Grierson asked him to direct a promotional film reminding Canadians to mail their Christmas cards early. This was Mail Early (1941), his first film at the NFB. He turned to animation without a camera, drawing directly on the film itself, just as he had done when he was starting out. He also worked on cartoons and animated maps for propaganda documentary films that were increasingly being used to give the public a better understanding of the geopolitical issues faced by a nation at war. This was followed by the Victory War Bonds campaign films: V for Victory (1941), 5 for 4 (1942), Hen Hop (1942) and Dollar Dance (1943).

V for Victory, Norman McLaren, provided by the National Film Board of Canada

Five for Four, Norman McLaren, provided by the National Film Board of Canada

Hen Hop, Norman McLaren, provided by the National Film Board of Canada

Dollar Dance, Norman McLaren, provided by the National Film Board of Canada

In 1942, film production increased considerably and McLaren could no longer do it all alone. Grierson asked him to recruit art students and create a small animation team; not an easy task, since many had gone to fight in the war. McLaren turned to the École des beaux-arts de Montréal and to the Ontario College of Art (and Design) where he met and recruited artists, some of whom would go on to play an important role in the NFB’s animation history, including René Jodoin, George Dunning, Jim McKay, Grant Munro and Evelyn Lambart, to name just a few. McLaren trained these emerging animators, who all worked on cartoons, animated cards and propaganda documentaries before going on to make their own films. A team of animators was on-site at the NFB in 1942. Studio A, the animation studio, would be a stand-alone unit as of January 1943.

As we look forward to 2013 and the 70th anniversary of the NFB’s first studio, I invite you to celebrate 70 years of animation by visiting the exhibition L’imagination comme bagage / The Inspired Imagination, now showing at Montreal’s Pierre Elliott Trudeau International Airport.

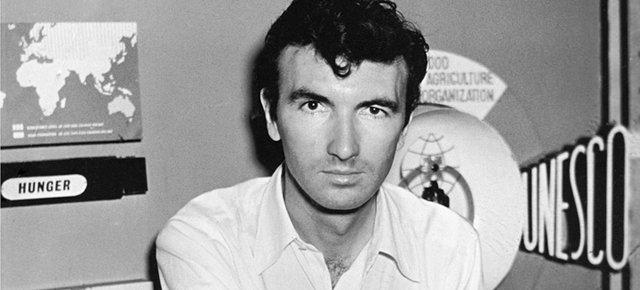

Photo: Norman McLaren in 1950, from the National Film Board of Canada’s Collection. All rights reserved.

-

Pingback: 70 Years of Animation, Part 1 – When Animation Marches Off to War | NFB.ca blog