Q&A with Michael Fukushima, Part 2

This is Part 2 of a 3-part interview with Animation Studio producer Michael Fukushima. To read Part 1 of the interview, click here. The third installment will be published on Monday, July 20.

In this installment, Michael talks about working with emerging filmmakers, the types of animation techniques used at the NFB and offers advice and tips for those interested in the industry.

JM: Is the NFB open to working with first-time filmmakers?

MF: Yes. We work with emerging filmmakers all the time. The reality of today is that the competition of ideas is so tough that proposals from first time filmmakers really have to stand out from the crowd. At the same time, it has to be scaled in such a way where we can say, “Okay, it’s a first time filmmaker but it’s viable. The budget is modest, it’s a 2 or 3 minute film, they’re talking about 16 months, not 38 months of production, etc.”

So, if already the young filmmaker has grasped these strategies, and is still able to deliver a passionate idea, then it’s going to stand out. But the truth of the matter is that so many film school graduates come to us with these elaborate, 20-minute ideas that they’ve been carrying around for 4 years of university that are just not viable.

JM: Is there an ideal time frame in regard to physical production?

MF: There are no set rules. Much of it depends on the technique and the temperament of the filmmaker. Many filmmakers will experiment and go off on tangents to try things out. There are filmmakers who are really quite focused and they’ll just plow through. Partly we’re trying to be humane. We don’t want a filmmaker to spend 3 or 5 years making a 10 minute film. I’d like a filmmaker to be able to finish an 8-10 minute film in 2 years because I think that’s a fair investment on our part, and not so onerous for them.

JM: What different kinds of animation techniques are practiced here?

MF: Over the course of time, we’ve done it all. Right now we’re still doing quite a bit of drawn, 2D animation. We do some analogue under the camera stuff with paint or Plasticine. We’re still doing stop-motion table top animation. Some CGI, but we’re not really a CGI kind of studio. We don’t have the infrastructure and the private sector does it so much better than we do.

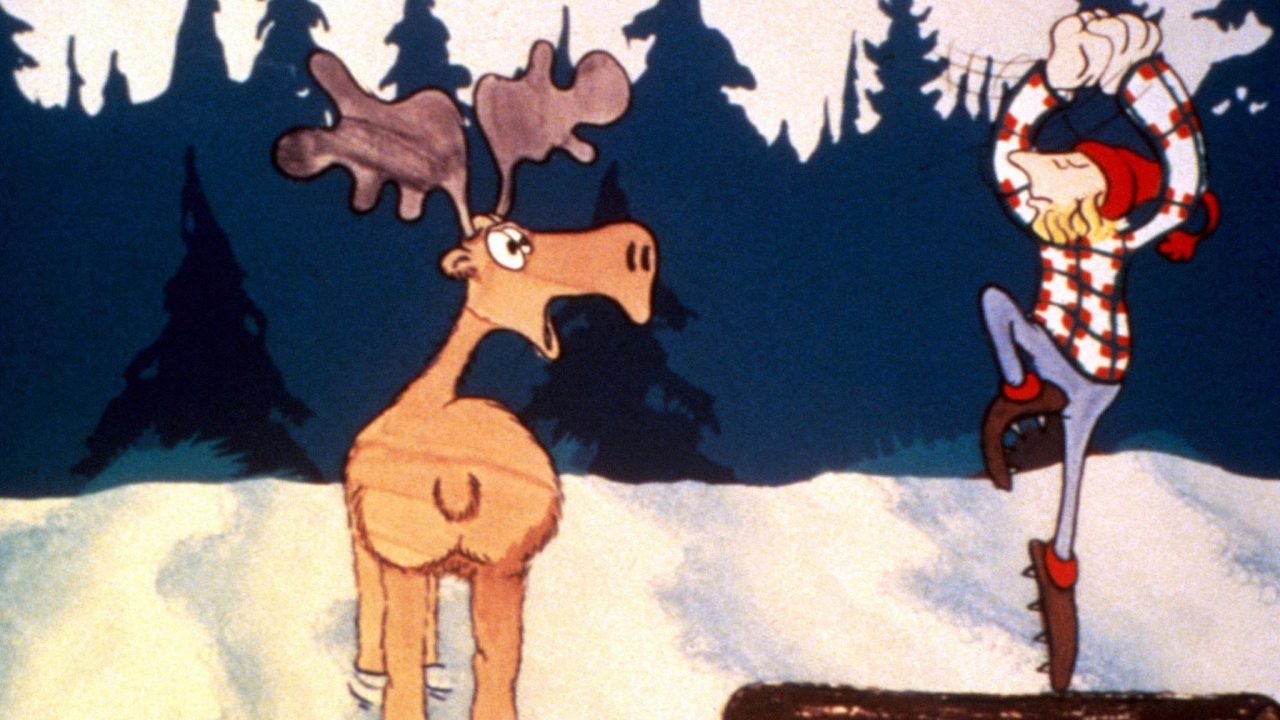

We do modified 2D computer animation, like what Cordell Barker did with Runaway, where parts are hand drawn but everything else is rendered digitally.

http://www.nfb.ca/film/Runaway_clip/

And of course, we do SANDDE animation here. We’re the only production studio in the world using this technique. SANDDE is a stereoscopic drawing technique and it’s a proprietary IMAX system. We’re the only studio in the world producing these SANDDE animation films. It’s a technique whereby an animator works literally in real time in a 3-dimensional drawing space and creates their animation using a drawing wand. They’re able to move their animation around in real time, in 3D space but it has a hand-drawn quality to it. A conventional CG film is capable of working in real time in 3D but all of the art is generated digitally by the computer.

JM: Is there a difference between 3D and Stereoscopy?

JM: Here at the NFB, we refer to 3D as stereoscopic filmmaking, which is how the industry seems to be embracing 3D. Fifteen years ago, 3D and CGI were intermixed all the time, because that was the only way it could be done. Nowadays, it seems like CG is for computer generated 3D animation and what the NFB is doing is stereoscopic animation. There’s also 3D presentation, like Hollywood is doing.

http://www.nfb.ca/film/sandde/

JM: In what ways has the NFB been an innovator in the field of animation?

MF: From 1941 to the mid-50s we were the only game around in Canada. So much, if not most, of commercial animation in Canada has some sort of foundation in the NFB, either someone was a filmmaker here and went off on their own or became an expert in a commercial studio either here in Canada or somewhere else in the world. We were one of the few big production organizations in the world well into the ’70s.

So, there’s a kind of seminal quality to just the fact of the NFB and animation. We were groundbreaking. Norman McLaren was a contemporary of a lot of experimental filmmakers in the ’40s, ’50s and ’60s. A lot of parallel innovation was being done in those days. We were one of the first places to start dabbling with computer animation [CG] in the ’70s and ’80s in partnership with the National Research Centre here in Canada.

http://www.nfb.ca/film/Hunger/

Ishu Patel came here from India and created the bead-under-camera animation technique. Some people like Caroline Leaf came and started doing paint-on-glass films, and then scratch-on-glass films and using IMAX film stock to make films. We had filmmakers from Hungary and eastern Europe come and perfect other techniques, such as pinscreen animation, while they were here.

So we may not have been pioneering in the way of Pixar, but our legacy comes from the fact that we invited filmmakers from around the world to come here and experiment, to have the luxury and freedom to try things on and see what worked and what didn’t work. The NFB has been an incubator, or laboratory, for experimentation.

JM: What are the different elements that make up the production team of an animated film?

MF: Director/animator, digital animator to handle After Effects or other parts of the digital work flow, an editor, sound designer, composer, a post production team, illustration team, mixers and engineers. Our film credits are probably the shortest of any production at the NFB and maybe 1/50th the length of a Pixar film. Even a Pixar short film.

MF: Do you hire interns?

MF: We do, but not often and it’s because of the auteur nature of our films. There aren’t a lot of natural places for an intern to come in. It’s a hit and miss process. But by all means, send in a letter to the studio. Everything gets looked at. We’re slow, but we’re thorough.

JM: What advice do you have for people looking to get into the field?

Don’t do it.

(chuckles all around)

I used to be an animator. You have to be obsessive-compulsive, so focused that you can work on a single 6 or 10 minute film for 2 years. That takes a certain kind of personality. So if you don’t have that, if you’re flighty or have ADD or get bored easily, this kind of animation is not for you.

If you love drawing, or art creation of any sort – puppets, sculpture, movement – if you have a sense of rhythm and timing and have a bit of closet ham in you, all of these things are valuable attributes to be a good animator.

To see them in public, animators are often introverts or shy, sitting in their offices hunched over their desks. But in order to make those inanimate characters live and breathe, there has to be some sort of theatricality and acting presence inside of them. You need that if you want the characters to leap off the page. Otherwise, it’s just movement without empathy.

If you have those qualities, this is the place to come. Drawing on its own is not enough. You have to really love drawing. You’re going to be drawing the same thing 6000 times. So if you love to draw, become a painter. If you can’t live without holding a pencil in your hand, then maybe you have what it takes to be an animator.

JM: What are your thoughts on film school?

MF: Film schools, including animation training, have been a boon in that they teach basic skills. You have the jargon, you understand what people are talking about technically and you understand the basics of the process.

The bane of film schools is that they only seem to graduate directors. A 21 year old whose only experience has been a few years of film school? Ninety percent of the time they just don’t have the life experience or the practice to tell a good, engaging story, which in the end, is all films are.

The thing about animation is that you need some fundamental skills to conjure up something from whole cloth. You have to be able to draw, or sculpt, or have some sort of artistic control to create something interesting. From the raw skills perspective, school training or mentorship is enormously valuable. Beyond that, you have to go out and start making films.

***

This series will conclude on Monday, July 20 with Michael Fukushima talking about Hothouse, an emerging filmmaker program in the English Animation Studio.