Commemorating the 30th Anniversary of the Genocide of the Tutsi People in Rwanda

Commemorating the 30th Anniversary of the Genocide of the Tutsi People in Rwanda

A duty to remember

This year, 2024, marks the 30th anniversary of the genocide of the Tutsi people in Rwanda. This is an important time to remember the tragic events of 1994, to honour the memories of the victims, to think about the future and to once more reflect on the slogan “never again.”

The three NFB films discussed here recall the horror and darkness into which humanity descended, yet again. They offer educators who specialize in the fields of peace and conflict studies, international law and other related disciplines the opportunity to reflect with students on the origins of the genocide. By examining the past while looking at events unfolding in the world today, students will be able to understand the characteristics of genocide.

The seeds of the tragedy

When I started elementary school, dividing students into Hutu and Tutsi groups was standard practice. It was also commonplace for teachers to speak rudely to Tutsi students. It was at school, when I was all of seven years old, that I learned I was Tutsi. I didn’t understand what was happening and I did not like being treated like an insect. Furthermore, identity cards for everyone over 16 indicated ethnicity and served as a de facto tool of discrimination against Tutsis in all walks of public life. It was very difficult, if not impossible, to be accepted into high school, university or the civil service. The political system in place at the time considered the Tutsi to be second-class citizens. Non-humans. And this made it easier to eradicate them.

The film Chronicle of a Genocide Foretold – Part 1: Blood Was Flowing Like a River shows the extent to which the world closed its eyes to the worst crimes against humanity. It reveals things the eye should never see and the ear should never hear—irrefutable proof of human and humanitarian failure. It is torture to see the survivors tell this story—a story of unspeakable suffering.

Chronicle of a Genocide Foretold – Part 1: Blood Was Flowing Like a River, Danièle Lacourse & Yvan Patry, provided by the National Film Board of Canada

Discussion topics

By reading about the characteristics of genocide as defined by the United Nations (https://www.un.org/en/genocideprevention/index.shtml) , and through an understanding of the genocide against the Tutsi people as seen in the film, students can reflect on global events and crises, and consider the methods and actions put into place to try to eradicate different populations.

From despair to action

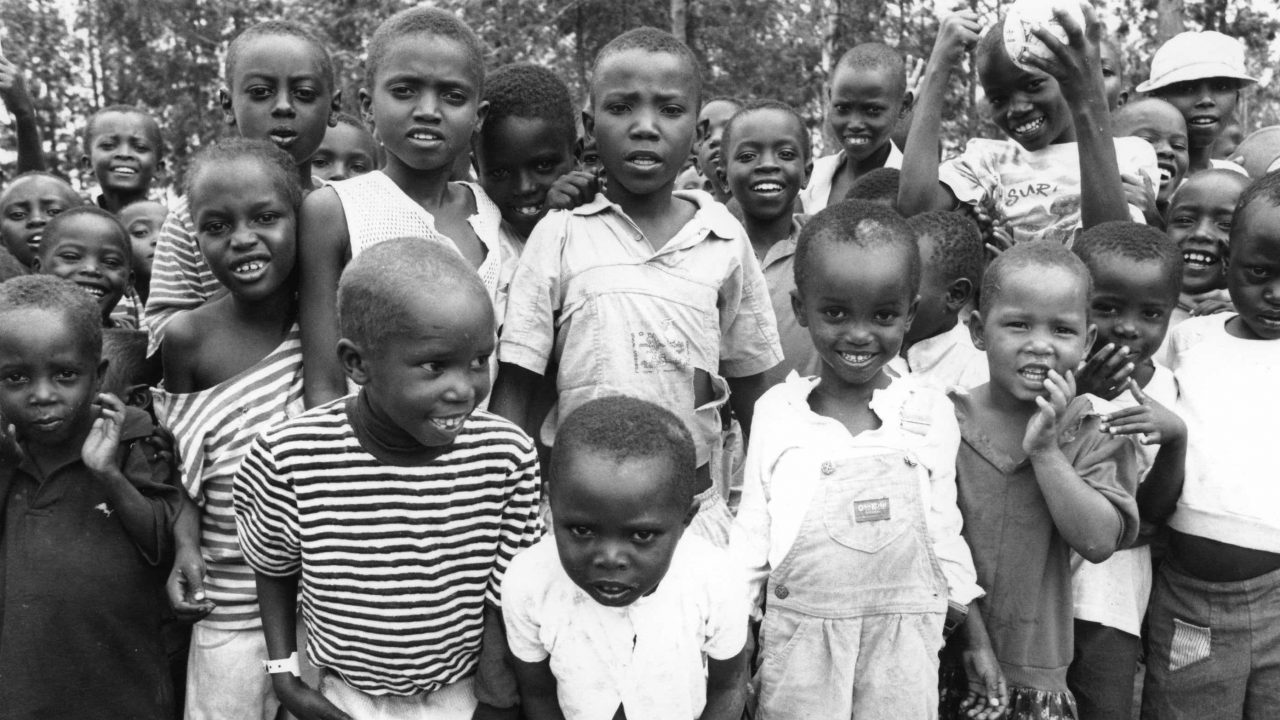

I witnessed discrimination and the rapid rise of hate towards Tutsis, which escalated all the way to genocide, robbing me of my old life. I survived these horrifying events, but my suffering and despair were so strong that I could not imagine having the strength to live again. One scene kept replaying in my mind constantly. We were at the St. Paul Pastoral Centre in Kigali, seated on the ground, with weapons pointed at us. A child with a cartridge belt walked by. He was with the soldiers and militia members who were going to kill us. His Tutsi teacher was seated beside me. The child recognized her and realized she was also going to be shot. The bullets he was carrying were going to be used to kill his teacher. (See my book On n’oublie jamais rien: le génocide comme je l’ai vécu , published in 2019 by Éditions Hurtubise.) When I thought about that child, I saw a whole generation—all these young people who had been turned into murderers, their innocence lost. I told myself that nobody is born genocidal. They are the targets of manipulation, hate speech and indoctrination, in Rwanda, towards a largely ignorant population held hostage by extremist Hutu politicians. These politicians were motivated by racism against Tutsis and wanted to carry out ethnic cleansing.

Having studied education science, I was driven by a desire to help reverse the trend, and to use the power of my will and my knowledge to promote teaching on a culture of peace through my research, my talks and my involvement with community organizations. Hate is learned, and peace can be learned, too.

The camp of shame

The Rwandan genocide was planned, prepared and executed as the world looked on. As with other genocides, the dehumanization of a people was the first step.

This genocide could have been avoided, but instead it was carried out to the end. United Nations forces in Rwanda were recalled, leaving an innocent population—men, women, children and the elderly—at the mercy of those carrying out the genocide. Faced with one of the greatest crimes against humanity, the world turned away, just half a century after the Shoah.

The documentary Hand of God, Hand of the Devil presents a gripping portrait of the complicity of the Catholic Church and international aid organizations. It takes a critical look at the role of the Canadian religious community, which founded the National University of Rwanda, as well as the part members of the Hutu intellectual elite played in planning the genocide.

Hand of God, Hand of the Devil, Yvan Patry, Sam Grana & Danièle Lacourse, provided by the National Film Board of Canada

Never again?

Fifty years before the events that took place in Rwanda, the world watched as six million Jews were exterminated in Europe. After the end of the Second World War, in the face of this horror, the international community came together, speaking with one voice, to declare that genocide should never be allowed to happen again. “Never again” became the rallying cry to keep humanity safe from these types of crimes. Nevertheless, the monster living in the depths of the human soul has continued to growl and to cause enormous harm. Is it a lack of political will or some other inability that prevents us from turning a declaration like “never again” into concrete structural support, sanctions and legal processes? Whatever the reason, the slogan remains meaningless and hollow since other genocides have occurred.

The film Sitting on a Volcano exposes the powerlessness of the international community when faced with an enormous number of refugees held hostage by a genocidal government. Rather than intervene in a timely manner, it fed and supported criminals because it was too hard to distinguish them from the innocent. It let through people whose weapons were still dripping with blood.

Sitting on a Volcano, Danièle Lacourse, provided by the National Film Board of Canada

Discussion topics

Here are some questions to ask after screening the films mentioned above:

- Who are the protagonists, in terms of the international community?

- What measures could have been taken to prevent or stop the genocide of Tutsis in Rwanda?

- What stopped the international community from taking those measures?

- What is preventing the international community from following up on declarations such as “never again”? What would allow it to take concrete action?

Peace education

Commemorating the events of 1994 provides an opportunity to reaffirm our commitment to preventing genocide, and to justice, reconciliation and building a future based on peace and mutual respect. It also allows us to remember that our achievements are fragile and that we must remain vigilant. Remembering is essential. As the philosopher George Santayana said, “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.” We must hold on to the memories so that we can pass down hope for the future and for humanity, in order to fight hate and allow our differences to enrich us.

Hatred, fundamentalism, intolerance and violence of all kinds are proliferating. More than ever, social media represents a dangerous and effective vector for all that threatens humanity. Together, we are responsible for taking care of each other, and for sounding the alarm in the face of intolerance.

The purpose of the transmission of memory is not to perpetuate recollections of horror. Rather, it aims to teach people, especially young people, to remain vigilant, defend human values and fight against divisions. It allows us to awaken new generations to the dangers inherent in the hatred of others, by showing them that war and genocide can be avoided. The history of genocide, the steps leading up to it and its consequences, should be taught in schools. Governments as well as national and international institutions must remember that genocide is the result of hate speech and division, and that it can happen anywhere and at any time. It is through education that we can understand the past, avoid making the same mistakes and embrace the future. According to the preamble of the UNESCO constitution, war begins in the minds of people, and it is in this same spirit that we must use peace education to erect defences against it. A paradigm shift is needed for us to move from a culture of violence to a culture of peace: a new paradigm in which individuals and institutions emphasize justice and the unity of humankind, and have the will to act without fear to support them.

Discussion topics

- What measures do you take, or can you imagine taking, to minimize antagonism, prejudice and fundamentalism in your community?

- What steps in this direction can you take when you consume or create content on social media?

- What could the elements be of a new way of thinking—one that favours sustainable peace and security for all peoples?

Marie-Josée Gicali has a Ph.D. in Education Science and is a survivor of the 1994 genocide of the Tutsi people. She is the author of the book On n’oublie jamais rien (We Never Forget Anything), published by Hurtubise in 2019.

Pour lire cet article en français, cliquez ici.

Discover more Educational blog posts | Watch educational films on NFB Education | Watch educational playlists on NFB Education | Follow NFB Education on Facebook | Follow NFB Education on Pinterest | Subscribe to the NFB Education Newsletter