Making The Tesla World Light: An Interview with Matthew Rankin

Making The Tesla World Light: An Interview with Matthew Rankin

The Tesla World Light is an electrifying short film about visionary Serbian-American inventor Nikola Tesla. Cinémathèque québécoise director Marcel Jean sat down with the film’s avant-garde creator, Matthew Rankin, for an illuminating Q&A.

The Tesla World Light, Matthew Rankin, provided by the National Film Board of Canada

- What does Nikola Tesla mean to you? What led you to make a film about him rather than some other scientific genius?

I’m interested in failed 20th Century utopias. We live now in the aftermath of these failures and that’s why, in my opinion, we’re now living in such an anti-utopian age. I see Tesla’s failure as one of the most beautiful and most tragic in the history of human endeavour. He was an idealistic scientist. He was sincerely convinced that his inventions were going to save the world and liberate the human race and he was utterly annihilated by the capitalist powers of his day. I found the image of Tesla, alone and unbalanced in his room, with his birds and his rejected ideas, to be just extremely touching.

There are times in life when failure becomes so huge, so monumental, that it becomes somehow majestic and grandiose; sublime failure is my greatest life goal.

- You develop your films in very direct relation to history. We meet historic characters, but they are seen in a very odd aesthetic setting that is anything but realistic. How would you describe this relation to history in your films?

I think of my films as false biopics – like Fellini’s Casanova (1976) or Cronenberg’s Naked Lunch (1991) or Steven Soderbergh’s Kafka (1991) —films that radically transform the factual record on which they are based. My background is in Québec history but, at a certain point in my studies, I came to the conclusion that I was an artist and not an academic. Academic historians must dispassionately measure the past in an effort to get as close as possible to an empirical chronology of fact, akin what Werner Herzog calls the “truth of accountants.” And yet there is so much about history that resists empirical measurement because so much of the human experience is abstract and ecstatic. How does one factually depict the feeling of Nikola Tesla’s nervous breakdown in 1905, for example? This the role of art. I like going into the subatomic particles of history, getting into the abstractions, looking for a truth that is truer than truth, which is really what art must do. Though in The Tesla World Light, I do stick fairly close to the facts (ha!)

- In The Tesla World Light, we catch references to Hans Richter, Viking Eggeling and other avant-garde artists. Were these references there from the outset of the project?

Yes. In his autobiography, Tesla says that when he was in a state of extreme emotion—fear, shock, depression, love—his eyes would become filled with shimmering abstract shapes of light. Tesla didn’t use the word, but I suspect that he had some sort of synaesthesia, a neurological condition in which, for instance, emotions become visually manifest. This detail immediately brought to mind visual music and the Lichtspielen of Richter, Eggeling, Walter Ruttman and Oskar Fischinger. I also think there are spiritual parallels that can be drawn between the artists of the avant-garde and a scientific futurist like Tesla. Radical abstraction belongs to both science and to art. For all these reasons, I use iconographies of the avant-garde to incarnate moments of extreme emotion in Tesla’s life: his discouragement, his love and, most importantly, the nervous breakdown that put an end to his active career in 1905.

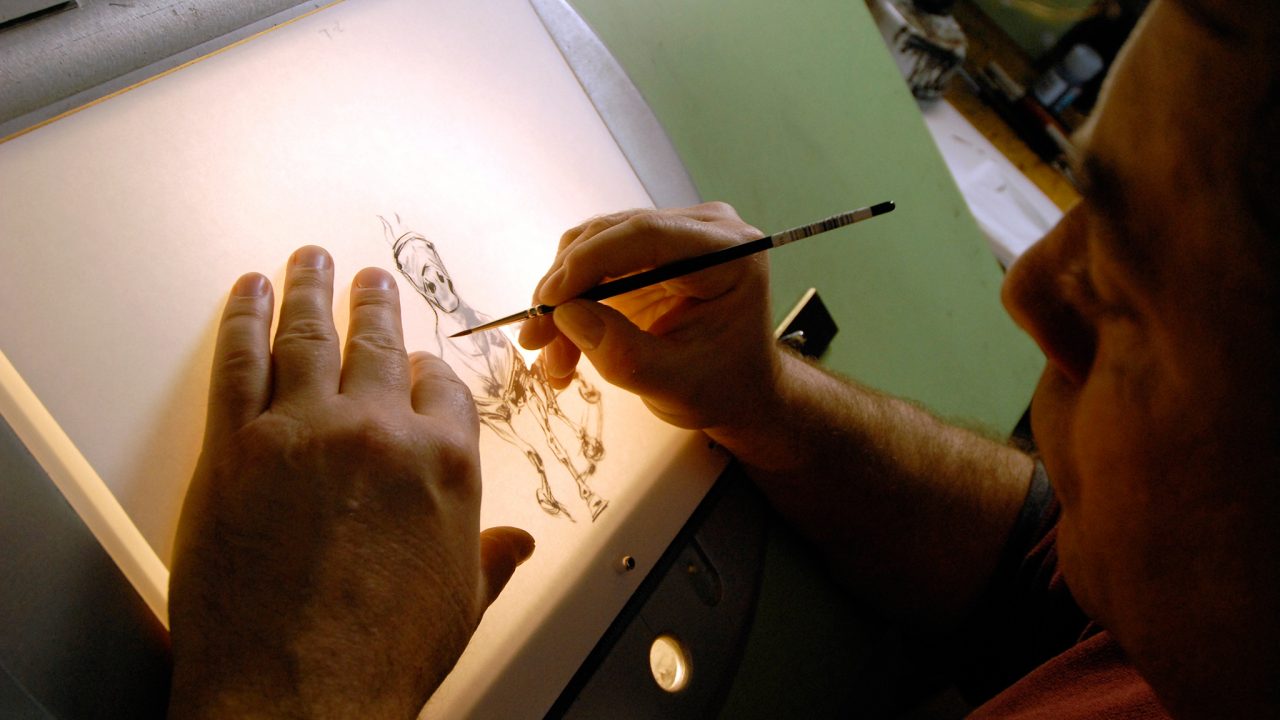

- Your films look very handmade. We see the use of traditional techniques, a very artisanal fabrication and a sometimes surprising mix of techniques. What is your relationship with technique?

My relationship with technique is that of a rutting salmon, ridiculously throwing himself upstream. I’m increasingly interested in images that are really, really difficult to create, and which have an extremely high potential for disaster. With each project, I’m trying to relaunch the Hindenburg.

As much as possible, I try to avoid any digital intervention or CGI, which, for the type of images I like to make, would be something of an artistic counterfeit. Let me be clear: some of my best friends are computers. But I do not find CGI to be a helpful artistic collaborator. I I really like hand-made images, made by humans, with all the artificiality, imperfection and humanity that come along with them. I am a big believer that most of the special effects that are worth retaining were devised between Méliès and Karel Zeman. So I always try my best to shoot on film and create my images in the camera.

- You’re often said to be a creator of strong, original images. That’s no doubt true, but in watching The Tesla World Light, one realizes that the soundtrack is very carefully crafted. What is your relationship with sound? Is it a creative aspect you put a lot of effort into?

Yes, a lot. Obsessively, even. With Tesla lumière mondiale, I had the great pleasure of working with the sound artist Sacha A. Ratcliffe. Her work is both dark and luminous, romantic and very otherworldly. She is really the perfect sound designer for Tesla. Early on in our collaboration, she made a replica of a radio instrument invented by Tesla which is known as the Tesla Spirit Radio. It is a very strange device that can receive and transmit the sound of light waves. The effect is totally fascinating. The intensities and textures of the sound vary according to the light vibrations, and Sacha created much of the background sound in the film with this bizarre machine. So it’s a film that’s completely composed of light, from the images to the soundtrack.

- In looking at the work of Guy Maddin, Deco Dawson and yourself, you get the impression that there’s an actual Winnipeg school of filmmaking. What’s your perception of that? Do you feel that you’re still part of a movement despite having worked in Quebec for so long? How do you explain the referential aesthetic that many Winnipeggers’ films have in common?

I would say that the connection between Winnipeg filmmakers is, more than anything, their predilection for bizarre humour. The first time I felt I recognized my city and my culture in a film was when I saw Richard Condie’s The Big Snit for the first time. Condie had an enormous impact on me when I was young. As a kid I did almost nothing but draw and I was shameless enough to send some of my drawings to Richard Condie—who lived not far from me—and tell him how much I loved his film. He immediately wrote back and sent me an original cel from The Big Snit as well as some tender words of encouragement, which are often scarce in a place like Winnipeg. I’m still very touched by his generosity. As for Deco Dawson, he bought me a Slurpee at a 7-Eleven a few years ago, which was also very generous—especially for Deco.

But to return to your question: yes, many generations of Winnipeg filmmakers share a fetishistic relationship—at once ironic and very sincere—with ephemeral, degraded and outdated forms of cinema. I think this stems directly from the existential situation of the city itself. Winnipeg is a very lonesome place, festering, as it must, in permanent exclusion from the North American mainstream. For those Winnipeggers who yearn for acceptance in the established tropes of mainstream Anglo-American success – fame, wealth, Stanley Cups – Winnipeg is can be a pathological source of frustration. But Winnipeg artists have always found huge, subversive inspiration in their city’s maligned and excluded status. Just trying to imitate the professional Spielbergian gloss of mainstream, “normal” cinema is factually unthinkable in a place like Winnipeg, and so filmmakers have sought instead to celebrate their own abnormality, to fetishize and remaster forms of cinema that the world has otherwise dismissed, forgotten, rejected. In so doing, they have elevated their city’s denigration into something great and beautiful, romantic even. There’s real creative wisdom and originality in that, and I’m really proud of my native city in that respect. This is the essence of what Toronto film critic Geoff Pevere once termed “Prairie postmodernism” in describing the films of John Paizs and Guy Maddin. I adore the films of Paizs and Guy Maddin, Deco, Astron 6, Erica Eyres, but I feel much more directly influenced by Solomon Nagler, who I consider to be a kind of cinematic father.

- The Tesla World Light is the first film you’ve made at the NFB. Did that change anything in the way you work?

I’m used to making my films in the subhuman underclass of independent shorts, so working at the NFB was very liberating for me. The NFB’s creative and technical infrastructure let me really take ALL my ideas to the limit, with no compromise. It was also in some ways my entry to the world of animation. My films are normally hybrid, but animators are much closer to the realm of fine arts, so I really feel at home with them. I feel I have discovered a new artistic homeland. I have also long admired the creative output of the NFB’s French Animation Studio. I believe it to be one of the world’s finest creative ecosystems, and it was an immense inspiration for me to work there.

-

Pingback: Animation News: Sharp Shorts for a New Millennium | | Tinseltown Times