Bread Will Walk: The “Baking-Of”

Bread Will Walk: The “Baking-Of”

Fresh out of the NFB’s creative oven, Bread Will Walk, a short film written, directed and animated by Alex Boya, is premiering at the Directors’ Fortnight in Cannes on May 22, 2025. The film’s story and aesthetic have been piquing the curiosity of more than a few intrigued fans and animation lovers.

This blog post offers just a taste of the unique recipe that Boya and the NFB’s team cooked up to give his latest batch its unmistakable flavour.

Genesis

It all started with the graphic novel The Mill, which Boya completed in 2018. Revolving around yet another circular, man-made shape, it was a natural follow-up to the universe he created in Turbine (2018), his previous film. Turbine was our first collaboration as producer and director and it cemented my opinion—formed back in 2012, when I discovered his work while reviewing student works-in-progress at Concordia University—that Boya is one of the youngest masters of surrealism in animation today.

So, in 2019, he shared his peculiar new project with me. It took us some time to position it for programming, but in May 2021, I felt immense joy when Boya immersed himself once again in the NFB laboratory. This time, his mesmeric “kneading” of the animation as an artform and a storytelling medium went on for four years! What exactly was his creative process like?

Story and mise-en-scène

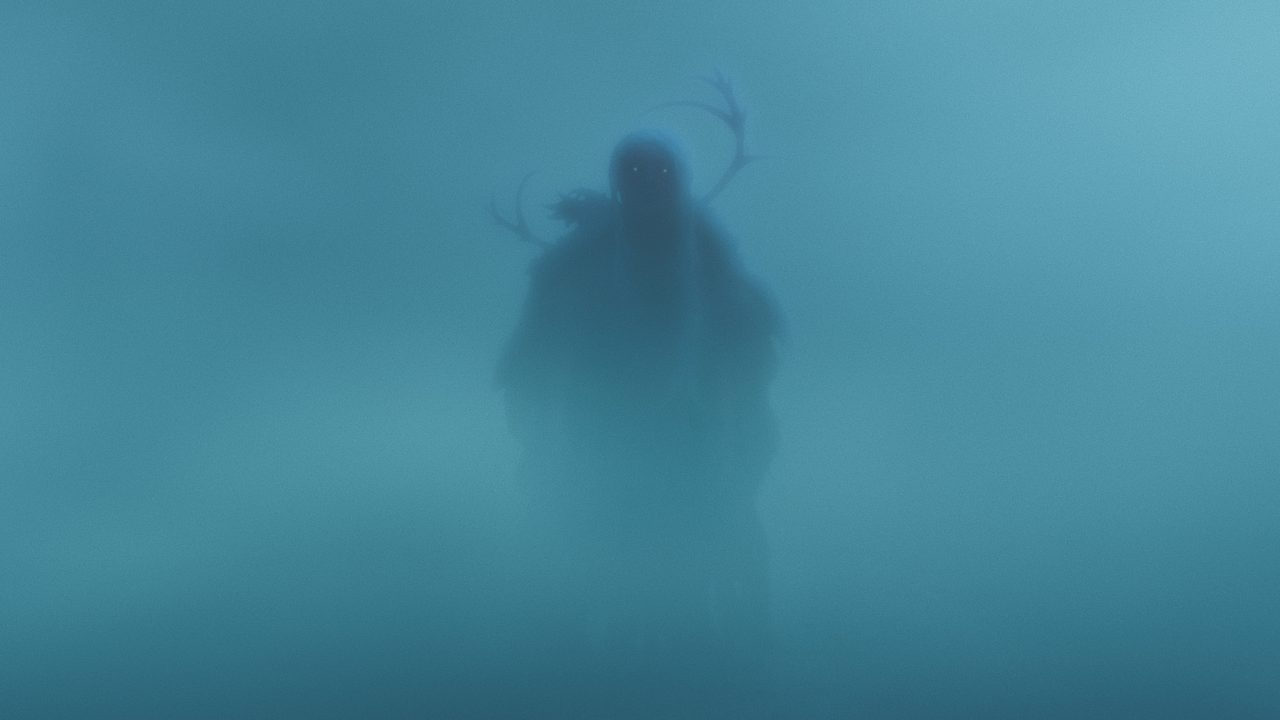

The first challenge we encountered was distilling the feature-length universe of The Mill into a 10-minute-long animatic of what was to become Bread Will Walk. In the starving world of the film, a devoted sister races to save her little brother, a bread-turned zombie, from the hungry mob. Can love defy appetite?

Even at this early stage, Boya’s surgical cinematographic vision was to create the entire film as one continuous shot. He had already started exploring that approach in certain shots in Turbine: the characters’ universe wrapped around them in the form of a constant “camera” reframing. But this time, he blew my mind with a relentless and breathless fresco of our times, where bread and circuses go terribly wrong, and all the animation magic happens oh-so McLaren-esque-ly in between the frames!

Look Dev “yeastification”

The visual style of the initial pitch was very much Boya’s hallmark design: big heads with small eyes unexpectedly full of life and emotion, using ink intaglio lines drawn on paper to create illusionary greyscale depth.

This traditional hand-drawn animation process was then enhanced with a simple photo collage of actual bread.

But how to animate that texture to Boya’s liking? He was adamant: “Bread has such an irreproducible porous texture that we should use only the real thing. It could not be simulated. So why not try stop-motion?”

Stop-motion trials

This part of the exploration started with tests using hand-made and 3D-printed stop-motion assets.

We even had serious discussions with Eloi Champagne, then the technical director at the English Animation Studio, about a small oven with heat-resistant green-screen paint and an animation rig to capture pixillation sequences of the baking bread. Obviously, the potential fire hazard this process posed was an issue when working on premises such as the NFB’s.

So stop-mo was ruled out and Boya went back to his first love: the light table.

Straight-ahead ink-on-paper animation

Boya then drew the full, straight-ahead animation pass—about 4,000 drawings in ink on paper for what was clearly going to be a single-shot film. These drawings were scanned and imported into Photoshop as a frame sequence.

3D environment tests

Boya began to open his mind to possible digital techniques and tools. After some rapid tests using Unity and VR 3D backgrounds, these options proved unnecessarily complicated, and the 2D pipeline seemed to be the optimal road.

2D photo collage

Boya then did a shape-segmentation pass on each of the 4,000 drawings in Photoshop, defining volumes and differentiating textures like skin, clothes, architectural structures, etc. The experimentation with 2D textures began.

The rough digital-collage pass produced satisfactory results for the overall look of the film, and most importantly, the bread textures.

However, the cohesiveness and density of the photographic footage was not fully in tune with the dream-like quality of the hand-drawn animation. The core of the illusion of animation was in peril, and McLaren was probably frowning down upon us. (His ghost, of course, frequently wanders through the NFB’s corridors, repeating his mantra that “what happens between each frame is more important than what happens on each frame!”)

AI-assisted tools

Then, Boya started testing AI-assisted tools using NFB in-house codes to create certain assets like texture or eyes. He quickly realized the limitations of such a visual aesthetic, rooted in data-based conventional looks and deprived of the unpredictability of true artistic design.

In Boya’s words, “it felt like adding prosthetics to my art; it did not satisfy the stylistic expectations or serve the artistic vision. It would always overpower it by regurgitating the statistical probability of what you ought to say instead of what you want to say.”

These assets were instead used as textures, volumes and light references for Boya to redraw and repaint over them frame-by-frame.

Final pass of linework and paint in Photoshop

So Boya spent the final two years of production applying frame-by-frame, hand-drawn and hand-painted interventions, and selecting different digital collage elements to be layered, masked and blended in Photoshop.

“Pastry glaze” meshing and blending pass

The film’s final adjustments were done by Mathieu Tremblay, the NFB’s English Animation Unit technical director, who applied what we referred to as a “home-made pastry glaze” filter. It was made in After Effects from full film renders that were created at the different stages discussed above, which were then layered, re-treated by section (white linework, black linework, grain, etc.) and re-blended. Tremblay also isolated certain levels of luminosity and applied specific blurs to them to obtain the perfect “pastry glaze” glow.

Conclusion

After four full years of “baking,” it’s safe to say that the film benefited greatly from the NFB’s unique creative kitchen, a one-of-a-kind setting that fosters innovation and experimentation in contemporary narratives. In this story, Magret, the sister sheltering her brother from the hungry living, is maybe Boya’s Antigone—a sort of glazed Monty Python–meets-Black Mirror Antigone, raising the question of whether the only antidote to our collective madness may be love.

As though created by apprentice bakers discovering the intricate (and temperamental) science of breadmaking, the animation in Bread Will Walk required trial and error before its secret recipe could be perfected. But the result is all the more surprising, delicious and comforting. Like bread itself.

Bon appétit!

Jelena Popović, producer of Bread Will Walk

ABOUT INNOVATION AT THE NFB

Since it was founded by Norman McLaren over 80 years ago, the NFB’s animation studio has served as a unique creative lab where artists have the freedom and resources they need to innovate and take risks. NFB filmmakers have been at the forefront of virtually every advance in animation storytelling, from drawn-on-film animation to stop-motion pixillation, from stereoscopic 3D to computer animation and much more. Whenever the NFB dives into new technologies, it’s all about boosting creativity and pushing limits—applying tech to trailblaze new ways of connecting with audiences through personal stories and unique visions.

Absolutely brilliant article! I also enjoy following Alex Boya’s Facebook group Walking Bread. So much fun!