The Forgotten Reels of Nunavut’s Super 8 Workshop: Wolf Koenig’s Treasure Trove of Footage

The Forgotten Reels of Nunavut’s Super 8 Workshop: Wolf Koenig’s Treasure Trove of Footage

This two-part blog post will wrap up my exploration of an intriguing and important chapter of Indigenous filmmaking at the NFB: the batch of films I recently found, made during the Frobisher Bay Super 8 Workshop in the mid-1970s (which followed on the heels of the successful Cape Dorset Film Animation Workshop, discussed in detail in two blog posts, here and here; to read my first post about the Super 8 workshop, click here).

Before delving into this precious archive of Super 8 footage—all made by Inuit filmmakers—I want to provide a little background on Wolf Koenig, who played a key role in this story. One of the NFB’s most celebrated filmmakers, Koenig had a hand in a long list of iconic NFB productions: he filmed Norman McLaren’s Neighbours (1958), created the animation for Low and Roman Kroitor’s Universe (1960), served as cinematographer on Low’s Corral (1954) and co-animator on Low’s The Romance of Transportation in Canada (1953), and co-produced Alanis Obomsawin’s Kanehsatake: 270 Years of Resistance (1993), to name a few. In short, Koenig was one of the creative masterminds (along with Kathleen Shannon, Norman McLaren or Tom Daly–among many others) during the “golden age” of the National Film Board of Canada.

Lonely Boy, Wolf Koenig & Roman Kroitor, provided by the National Film Board of Canada

Koenig also worked in the renowned Unit B (under Daly’s lead), which produced Candid Eye, the highly influential series that changed cinema forever, as it shaped what is today known as Direct Cinema. The films directed or co-directed by Koenig, including City of Gold (1957), The Days Before Christmas (1958), Glenn Gould – Off the Record (1959), Stravinsky (1965) and Lonely Boy (1962, featured above), about Paul Anka, the Canadian singer-songwriter who wrote Frank Sinatra’s signature song, “My Way,” are classics of non-fiction storytelling and founding archetypes of documentary cinema.

Wolf Koenig’s Treasure Trove, as Told by Donald McWilliams (50 Years Later)

Educator, director, producer, and history keeper Donald McWilliams began his career as a filmmaker in 1971. He was working as an elementary school teacher in Burlington, Ontario, when, thanks to his audiovisual work with children (he taught them how to make films using McLaren’s method), he was invited—along with 23 other teachers—to spend six weeks at the NFB in Montreal in the summer of 1968.

In the years that followed, McWilliams interviewed McLaren and wrote an article about him, in addition to making a 16 mm film, based on an idea given to him by McLaren. The experience led McWilliams to decide to become a filmmaker and for a period of time, he had the luxury of having McLaren as his teacher. McWilliams went on to direct several acclaimed films, including one of the most important NFB productions of the last year, A Return to Memory (2024), a look at the wartime years when women played a key part in transforming the NFB into a major international studio.

A Return to Memory, Donald McWilliams, provided by the National Film Board of Canada

Two months after the publication of “The Forgotten Reels of Nunavut’s Super 8 Workshop: Mosha Michael,” McWilliams reached out, saying, “I have just read your fascinating piece on Inuit filmmaking at the NFB; I learnt a lot…” The blog post had helped him place in context a box of Super 8 films he’d looked after for 30 years! In his message, McWilliams also provided me with the following backstory:

“Initially, back in the 1970s, I made films in Super 8; in the many visits to the NFB and McLaren, he introduced me to people there such as Tom Daly, Evelyn Lambart, Grant Munro and Wolf Koenig (the latter, at the time, passionate about Inuit having the wherewithal to express themselves instead of being patronized by the whites from down south, as you mentioned in your blog post).[i] One Friday afternoon, somewhere between 1972 and 1975, when Wolf was in his second stint as head of English Animation at the NFB, he suddenly changed subject and questioned me:

- “You’re an expert in Super 8?”

- “Well, yes.”

- “How would you like to work with Inuit?”

- “I would love it.”

- “Would you go up North?”

- “Yes, when?”

- “Tomorrow.”

- “But, Wolf, I live in Toronto and am in the middle of a project. Could I go in couple of months?”

- “No, Don. It has to be tomorrow.”[ii]

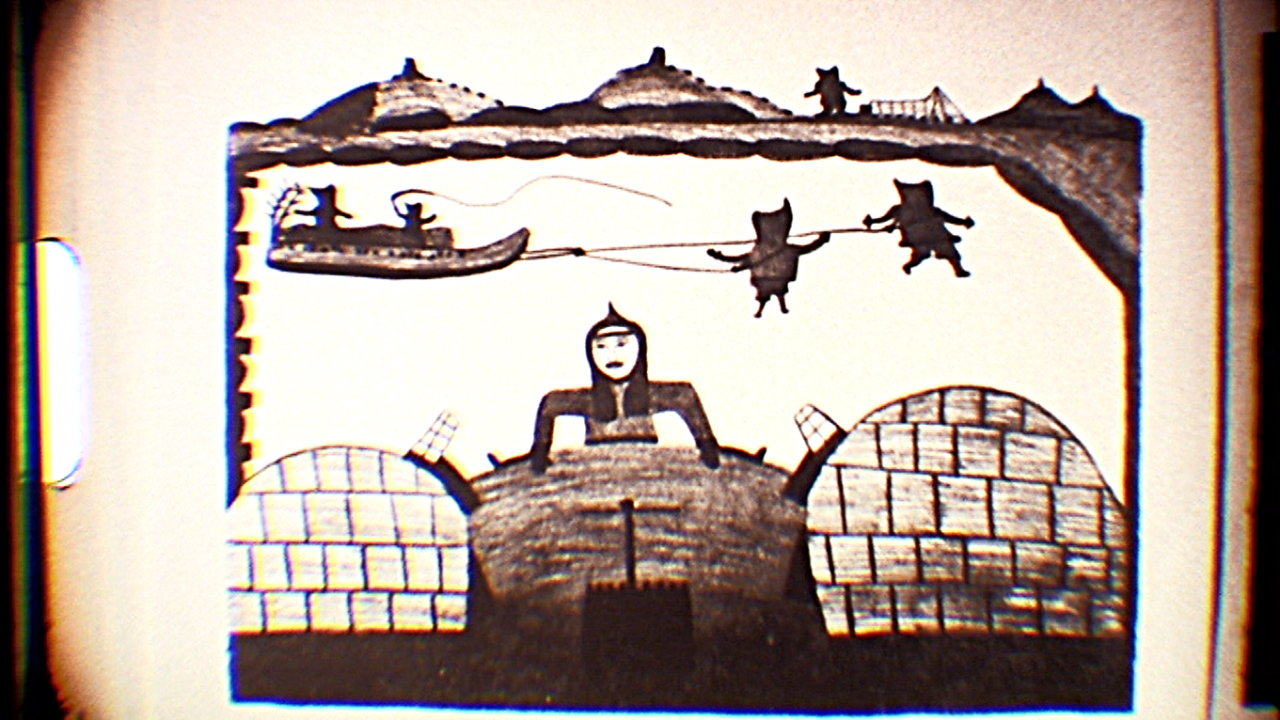

McWilliams never made it up North, where Koenig had initiated a Super 8 filmmaking program in 1975, in which Inuit directed, wrote, edited and narrated all the material themselves—in addition to filming many hours of footage—that would be output onto tapes to be shown on the CBC’s Northern Network.

Koenig retired from the NFB in 1995, and in his office, he had a box that contained all the Inuit footage, shot on Super 8 with sound. He gave this box to Don Haig, who was head of English production; Haig left the NFB just three years after Koenig and gave the box to Donald McWilliams. After checking the material on a Super 8 Steenbeck, McWilliams created a preliminary catalogue of its contents, then put the box into the NFB’s nitrate vault to protect the footage, where it remained for over a decade.

Arctic Defenders, John Walker, provided by the National Film Board of Canada

Then, in 2011, more than 15 years after Koenig’s retirement, McWilliams found out that the NFB executive producer for the NFB’s North West Studio in Edmonton at that time, David Christensen, was working hard to once again establish creative relationships with Indigenous artists, so Don reached out, and that led to a film lab in Toronto digitizing the picture and sound of the Inuit Super 8 footage in HD.[iii] The 2013 NFB film Arctic Defenders (embedded above), directed by John Walker and produced by Alethea Arnaquq-Baril, includes some excerpts of these Inuit films from the ’70s; apart from being an insightful film, it’s enjoyable to watch Arctic Defenders and try to spot this original Super 8 footage included in the film!

Diving into 19 Hours of Inuit Cinema

Thanks to the support of various colleagues at the NFB (particularly in our film conservation department), I was finally provided with the digitized collection of Super 8 footage. I was able to access 63 files, which contained about 19 hours of edited footage, comprising (conservatively) roughly 36 films.

Fifty years after it was produced, I’m going to try to provide a general review of the footage—to the greatest extent possible, while respecting language and cultural barriers—in the next and final installment of “The Forgotten Reels of Nunavut’s Super 8 Workshop” (click here to read it).

[i] Communication provided by Donald McWilliams for the use of this blogpost.

[ii] IDEM

[iii] IBIDEM