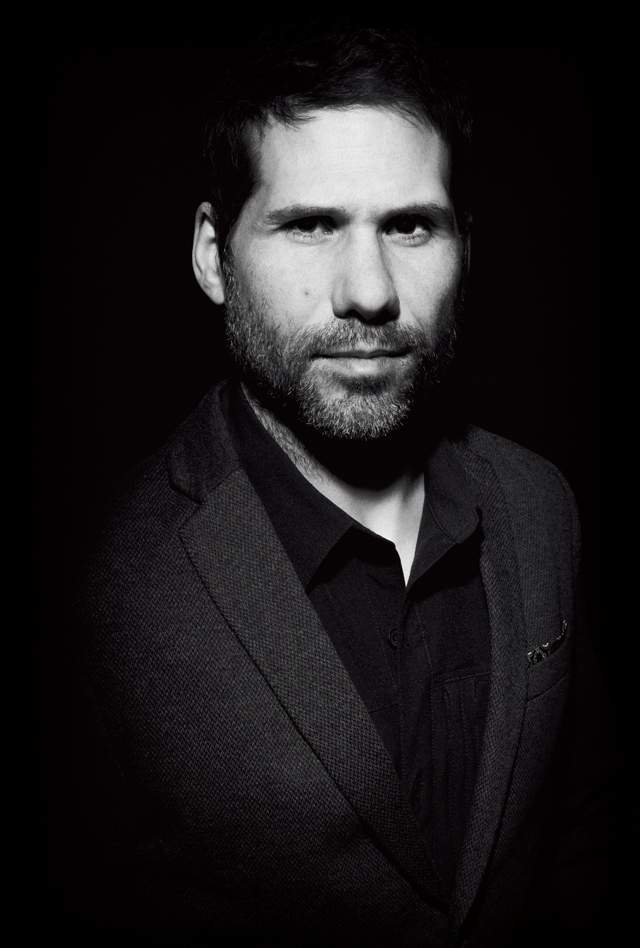

Charles | Interview with filmmaker Dominic Étienne Simard

Charles | Interview with filmmaker Dominic Étienne Simard

It took over four years to complete Charles, an animated short that Dominic Étienne Simard is about to launch this year. Like Paula, released by Simard in 2011, this drama uses traditional animation to depict a child who grows up too fast. But the creative process for making Charles also entailed a number of things that were new to the filmmaker. Simard tells us what it was like working on his first Canada/France co-production and creating his first film in collaboration with other animators. He also explains the peculiarities inherent to Charles and the trilogy to which the film belongs.

Producing Charles spanned several years. Can you tell us how the project came about?

The film was developed from a script I wrote for the SODEC Cours écrire ton court competition. In 2012, it was devoted to animation and I won the prize. That was already good news for funding. Then, I had Julie Roy at the NFB read the script. Together, we decided to do a co-production with France.

How did you go about setting up this kind of international co-production?

We initially approached a French producer directly, but it didn’t work out very well. I was willing to make changes to the story, but after two meetings on Skype, I knew we didn’t have the same vision. So we decided to approach another producer: Dora, at Les Films d’Arlequin. This time, it clicked right away. Then we contacted the CNC for funding and Ciclic, which provides arts residencies.

In Canada, I submitted the project to the Quebec Council for Arts and Letters and SODEC, and it was accepted at both places. It was kind of like a funding grand slam! Then ARTE got on board. The funding process was long – about two years, from the first application – but it turned out great. We contacted a lot of institutions, but the process was easy and positive.

So Charles was created on two continents. How did your arts residency in France go?

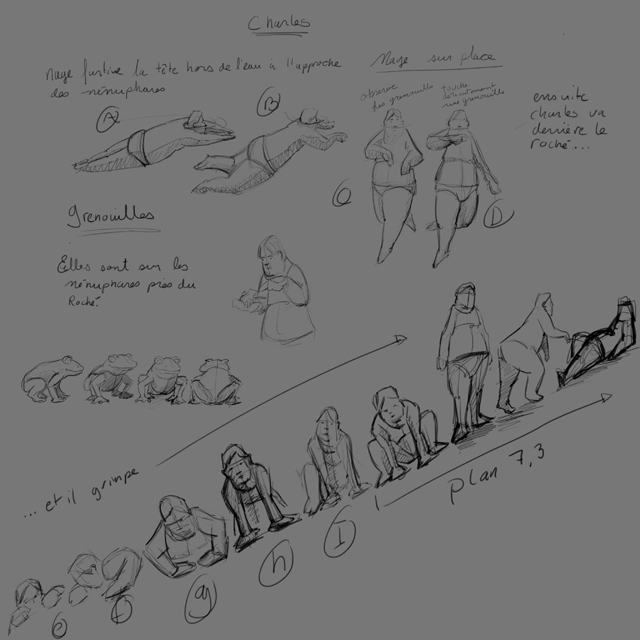

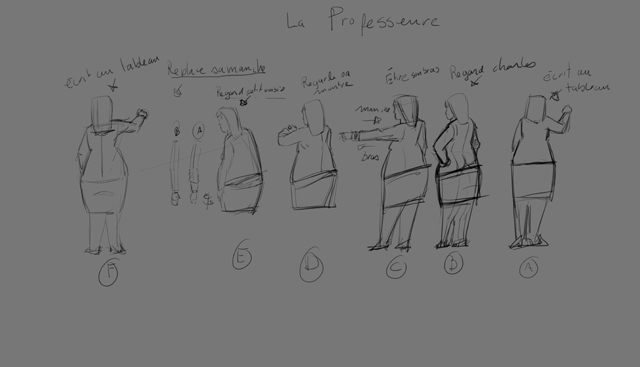

I spent several months at Château-Renault, a tiny village in the Loire Valley. That’s where production began. It was strange and very disorienting because there’s really nothing there. It forces you to focus on the project, but it wasn’t easy to fill up your free time. I worked with the French animator Benoît Chieux, but everything was done remotely because he was in Valence, 500 km away from where I was. I sent him files with drawings and poses… I explained the animation shot by shot, the intention for each one, with the sets and all.

Is it hard to work with an animator when you’re used to working alone?

Yes, but the collaboration went really great. I even worked with several animators: Benoît in France and, later, Jérémy in Belgium, Jens and his assistant François in Canada. I was nervous at first. We had to adapt. But Benoît has a lot of experience and he was willing to adapt to my way of working, which isn’t very orthodox. His sensitivity was the closest to what I was looking for. Animators are a bit like actors, if you know what I mean. Choosing the right animator is like casting for a movie. They all have their strengths and weaknesses. We had them take a test and Benoît was really the ideal candidate. I could sense the project was in good hands.

How is your work method different?

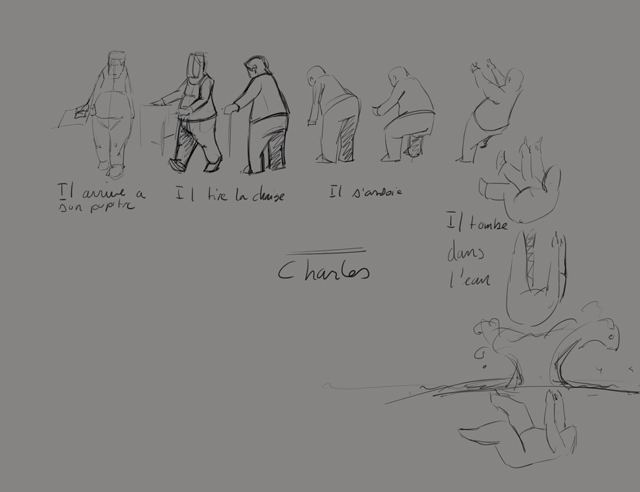

I don’t do a storyboard and all that. I just start with the script and I never know what the next shot will be before I begin. It’s scary for producers! (laughter) It takes a solid base of trust. But that’s what I’ve always done and the results speak for themselves. For me, doing a storyboard would be like mapping out what I won’t do. In animation, you have time to see things coming. You work for weeks on a shot, so you can already be thinking about the next one. Everything moves into place, even when it’s not really because of a conscious effort. I let the idea emerge.

How does Charles compare with other animated shorts you’ve created?

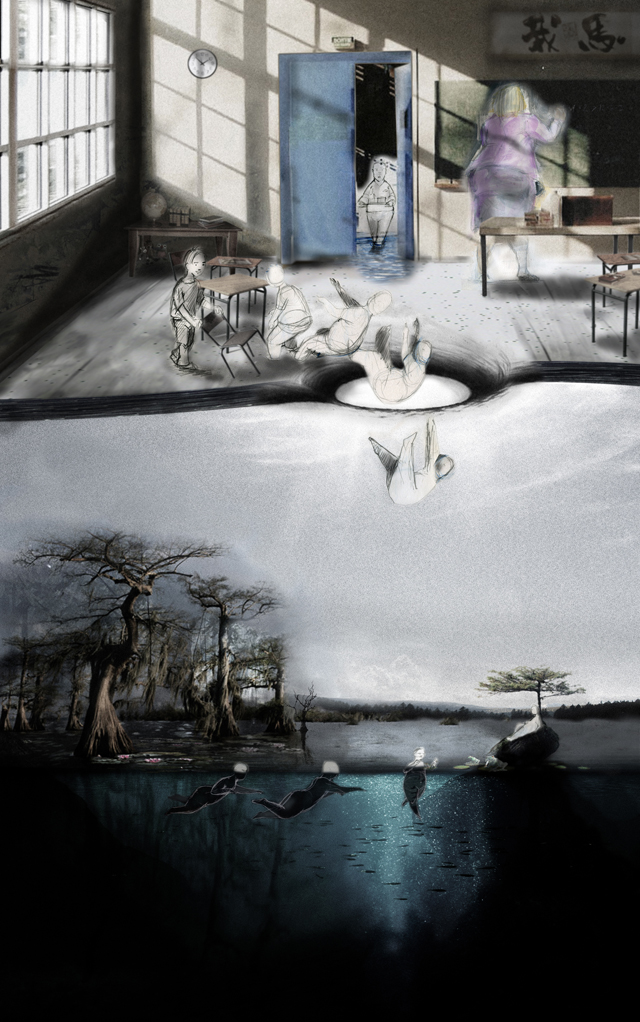

It’s a variation on the same theme as Paula – the child prematurely propelled into adulthood -, but the treatment is different. In Paula, what’s hard hitting is the assault. The entire film leads up to it. At the animation level, there are strong brush strokes, coarse textures. In Charles, it’s more insidious. It’s a progressive descent. Charles is an overweight child who gradually becomes an adult because his mother retreats from handling family responsibilities. Everything’s slower: the staging, Charles’ movement, the animation. Everything’s more delicate, even the shading.

In the beginning, I knew I wanted the animation to be less rough than for Paula, but I was still thinking of something fairly energetic. Except that I had to adapt the animation so that it fit in better with the staging I wanted. The shots are relatively long: most of the time in an animated film, the shots are 3-4 seconds long, but in Charles, they last on average around twenty seconds.

Creating Paula was really hard for me because it put me in a particular state of mind. I really enjoyed making the film, but I also had a lot of trouble finishing it. The violence in it is something I wasn’t always comfortable with. It hurt. With Charles, the process was less painful.

How did the work continue once you got back to Montreal after the residency?

When I got back, I had a lot of integration work to do. After that, I started working with the animators in Canada for a little over six months. I worked on the sets: they’re montages of snippets of photos I took here and there… but if I hadn’t told you, you wouldn’t have known! There’s a lot of grain, texture. Everything is pretty simplified, “desaturated” to remove information. And the rest – what moves on those photos – is traditional animation. Then, there’s the sound: it’s quite a job!

Who did you work with for the film’s sound?

Oliver Calvert for the sound and Ramachandra Borcar for the music. He’s the one who did the music for Paula and we worked the same way: I gave him some stuff I listened to while animating and he took it from there to find the right emotion. There was a lot of Daniel Lanois, and things like that. His work is really strong, and all the sound editing, too. I have a lot of respect for that: it’s not easy to find the right atmosphere, the right mix to express my intentions and bring out the story in the best way possible. You don’t want to overdo it. I’m really happy with the result! And it’s weird, because it took years for the visual work, while all of the sound was finished in roughly two months. It’s disproportionate, when you think about it.

Now that Charles is finished, do you know yet what your next film will be?

As a director, I enjoy never doing the same thing again, and playing with the film language, both from a visual and sound perspective. I like making variations, coming up with completely different ideas. I need to change the parameters. I haven’t written the next one, but the approach will be different for sure. I might move to dialogue, for instance, since there isn’t any in my other films.

I have an idea, but I haven’t found the triggering element. I want to do a trilogy, three ten-minute films, like another variation on the theme of the child who moves too quickly toward adulthood. I’d like the character to be a girl this time, even though I haven’t decided how old she’d be yet, and for it to be told from the parents’ point of view.

So your animated films start with a story and not the visuals?

Animators often begin by drawing and then start to learn how to make films. I came to drawing by accident, when I was in my early twenties. I learned how to draw so that I could do animation. I wasn’t supposed to do it, but I thought it was a form of creation that better suited my personality than live-action shooting did. I start with a script and develop the visuals to go with the story. Writing comes first. Next comes very traditional animation. It’s a really long process: I do a drawing and then I do another one…It’s a daily routine. Animation takes perseverance. It can’t be said enough, but that’s especially where the difficulty lies.