Montreal, 2050: When Bubbles Have Replaced Masks

Montreal, 2050: When Bubbles Have Replaced Masks

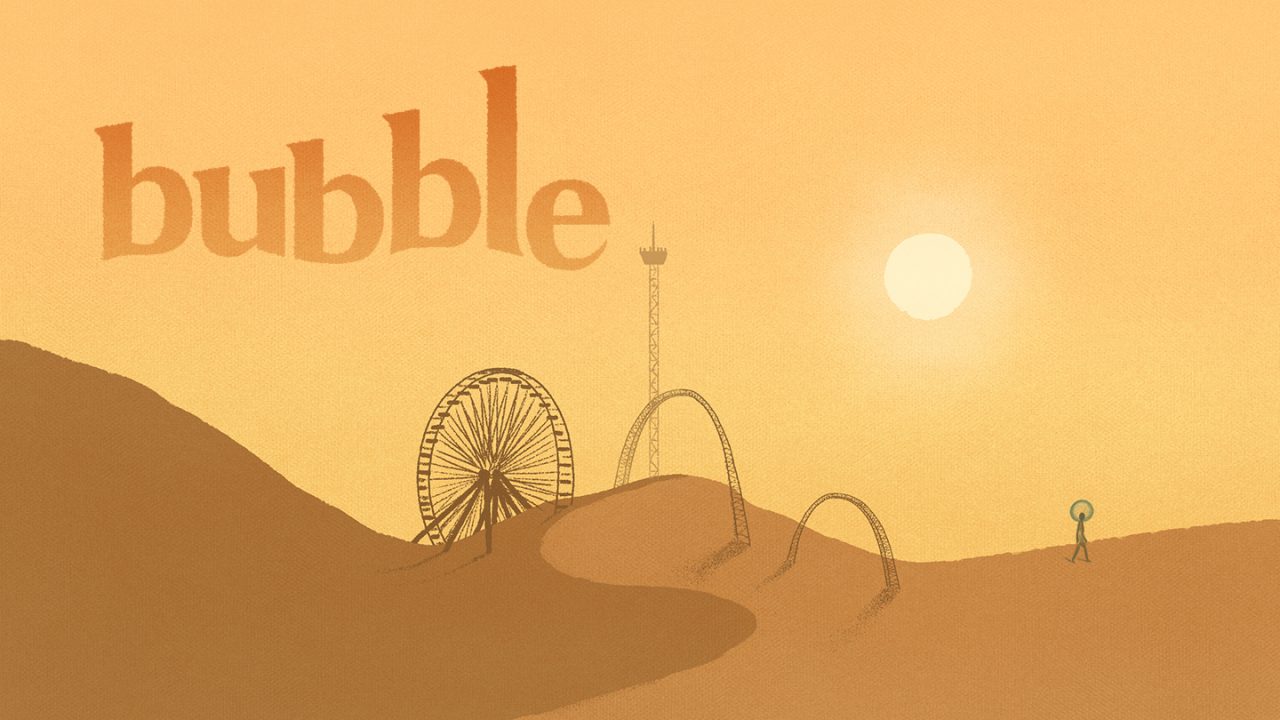

The Bubble interactive experience was created over a year ago at the NFB’s interactive studios by eight UQAM student interns. I was one of them. Set in 2050, Bubble imagines a world in which nothing has been done to slow down global warming. Some would call it a pessimistic vision. We prefer the term realistic.

Our NFB adventure began in April 2019, when we were asked to create a project about Montreal’s resilience in the face of environmental change—to imagine our resilience, our future. By consensus, we had determined that we wanted to take an optimistic approach, countering the widely held view that young people are fatalistic and exaggerate the dangers associated with climate change.

We recognized that setting the work in 2050 represented a challenge. There are many different environmental projections, and we wanted to stick as close to reality as possible. Throughout this project, we’ve been guided by our desire to make change—to wake up those who’ve been sleepwalking through the threats posed by the climate crisis. It’s a desire many young people of our generation share. We saw ourselves as speaking for a generation tired of shouting about how urgent the situation is, only to be accused of crying wolf. This is why we treated our future as though it were our present. We did not want to be seen as just another group of pessimistic youth.

We relied on different sources, including reports from the IPCC, and on the support of experts from UQAM’s Institut des sciences de l’environnement. The theory of collapsology also provided a cornerstone for our work. According to the Collapsology Portal established by Pablo Servigne and Raphaël Stevens, who are thinkers on the subject, collapsology “rests on the conclusions drawn by numerous scientific disciplines to understand and predict the dynamics of the decline or collapse of social and ecological systems that could lead to the end of industrial civilization.” In other words, it rests on the premise that climate disruptions are very real and will radically transform the world as we know it.

This was a theory that spoke to us. And while it created the impression of an imminent ending, it also carried with it a sense of renewal. Of an “after.” The other studies we consulted all pointed to similar conclusions: we have reached a point of no return when it comes to the environment, and we will have to live with the consequences of the climate crisis.

Our research also showed that while extreme climate events may be rare right now, they will soon be part of our everyday lives. In his article “Les changements climatiques et leurs impacts” (“Climate changes and their impacts”), climatologist Alain Bourque writes: “The anticipated increase in certain types of meteorological extremes has the potential to produce impacts whose scope may be as catastrophic as it is spectacular.”

Think of the forest fires in Australia and California, the floods at Sainte-Marthe-sur-le-Lac, Quebec, in spring 2019, or the multiple heatwaves this past summer. There is something apocalyptic about the thought that these types of natural disasters will occur more and more frequently.

We will have to change our cities so that they’re more resilient in the face of these upheavals. Indeed, this is already happening: urban agriculture, the greening of streets and alleys, and air-conditioned rest stops are among the solutions Montreal has begun to put in place over the last several years to help adapt to our changing climate.

We believe that the ability of cities to be resilient in the face of disaster rests with individuals. Just look at the current pandemic. It’s clear that we depend on the public’s cooperation to survive, yet some people still remain reluctant to cooperate.

Some seem more put out by the violence of being locked down at home than by the daily death toll in the thousands. Is it going to be the same with environmental disruptions? Will we see this same “me, mine” attitude when we face an overwhelming number of deaths linked to the climate crisis?

These are the reasons that, when the NFB’s interactive studios asked us to think about daily life in 2050, we couldn’t help imagining a weakened, out-of-breath, individualist Montreal. It seemed like this would be closer to our reality. It’s what the science also appears to show.

COVID-19 took us by surprise. We believe that environmental havoc will do the same if the status quo persists. We will not be able to make progress on this front until we overcome our archaic and individualist outlook in favour of a more collective approach to the future. This will only be possible once we’ve accepted that the warnings of activists are realistic, not pessimistic.

The world as we know it is in the process of being transformed, whether we like it or not. Cities and individuals will have to adapt, whether through lockdowns, wearing a mask, or putting one’s head in a bubble.