Two Apples: Not Your Grandmother’s Claymation

Two Apples: Not Your Grandmother’s Claymation

When you don’t know much about a film before going to see it, but you’re told that it’s clay animation, you might imagine stop-motion Wallace and Gromit-esque 3D characters, with slapstick movements and toothy smiles. But if the film you’re seeing is Bahram Javahery’s Two Apples, it won’t deliver on any of those expectations.

The film tells the touching story of a woman who immigrates to a new country, and what it means to only be able to take a little bit of your homeland with you while leaving the people you love behind.

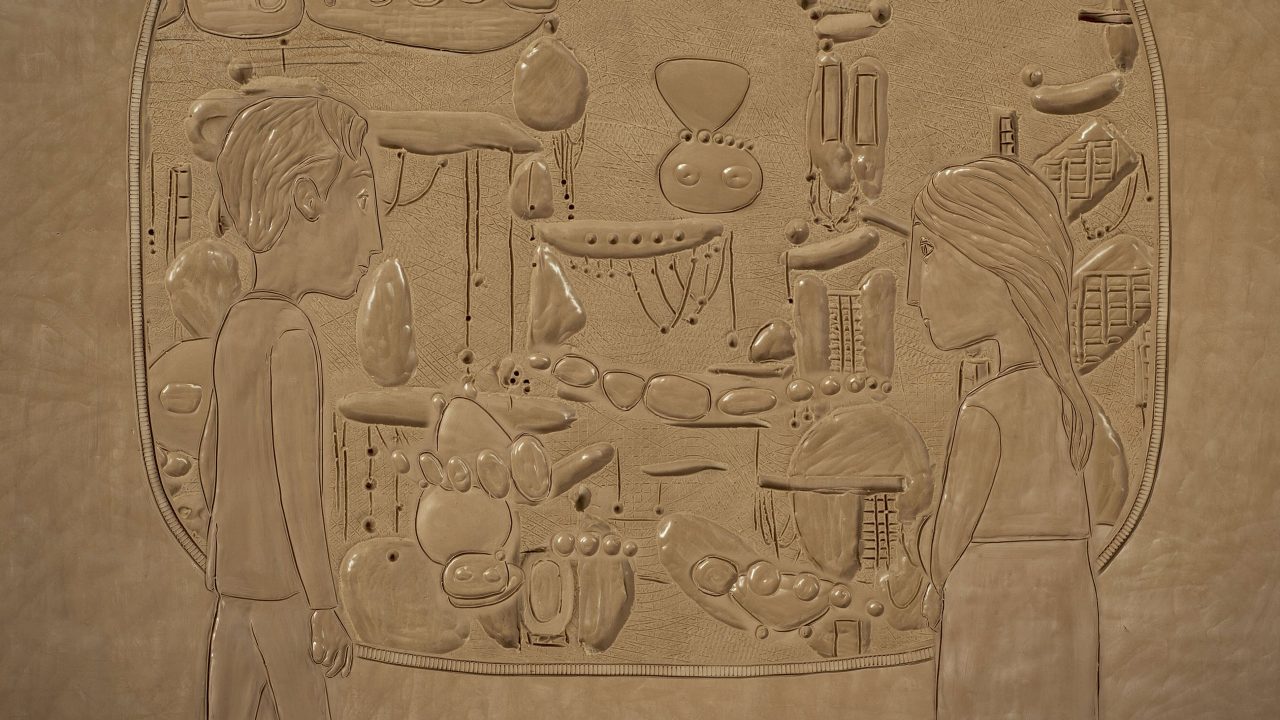

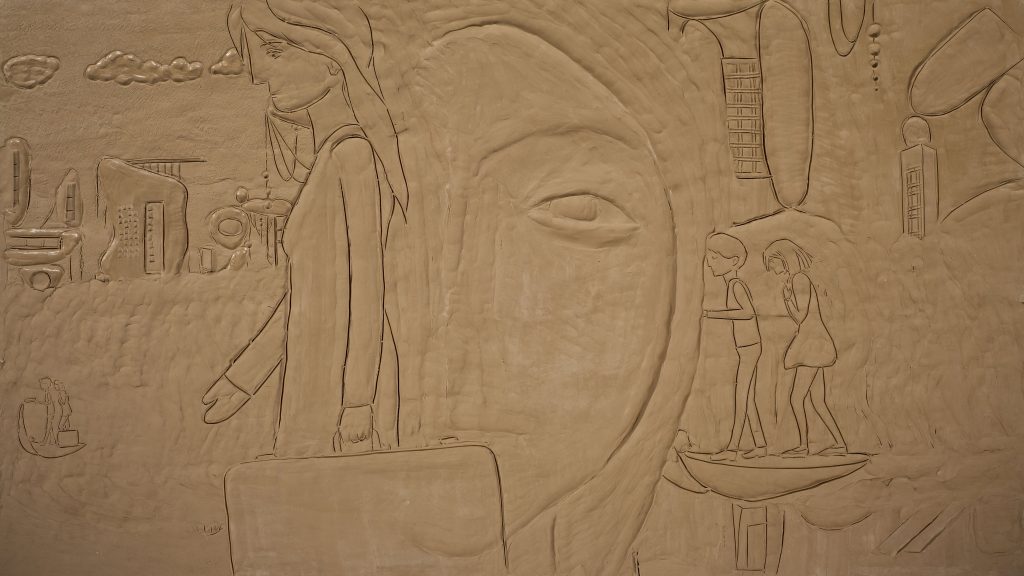

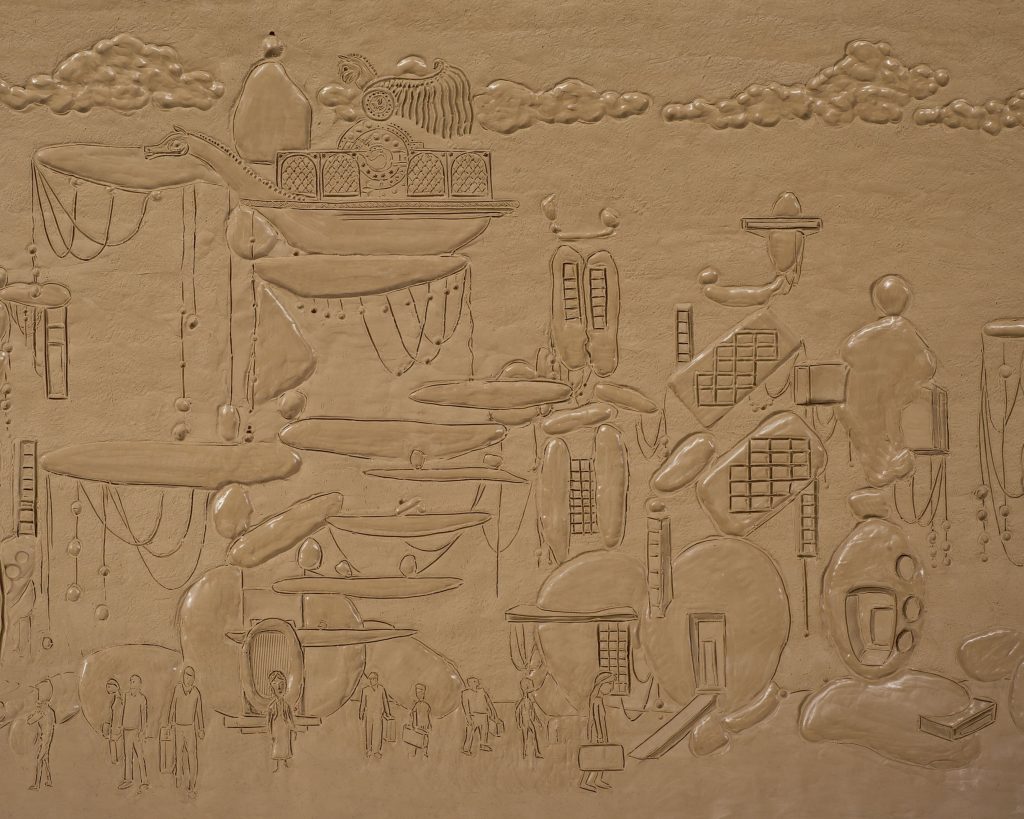

But the way that story is told is what sets Two Apples apart. Each scene is hand-carved onto a flat slab of clay, animated through a series of bas-reliefs that transition in a remarkably fluid manner. Sometimes it’s simply the characters going from point A to point B in a logical fashion; other times, the image is literally transforming into something new or, most impressively, showing us a spinning zoetrope. It’s both mesmerizing and jaw-dropping.

Two Apples, Bahram Javahery, provided by the National Film Board of Canada

So how did Kurdish filmmaker Javahery create such smooth transitions?

“Very carefully,” he told me.

He was trying to avoid choppiness and specifically aimed for the nearly liquid flow we see onscreen. But carving was just one part of producing this effect. To make it look like the characters were busting out of the slab, Javahery essentially created an optical illusion.

“Usually, light shines from the top, so a ridge looks darker below it and lighter above, but a depression looks brighter below and darker above,” he explained. “I’ve found that it’s easier to make a dent in the mud than it is to make a bump. I created images by carving a depression into the clay, and then placing the light source at the bottom of the frame, setting the light direction from bottom to top. This creates a small shadow which makes the images look 3D.”

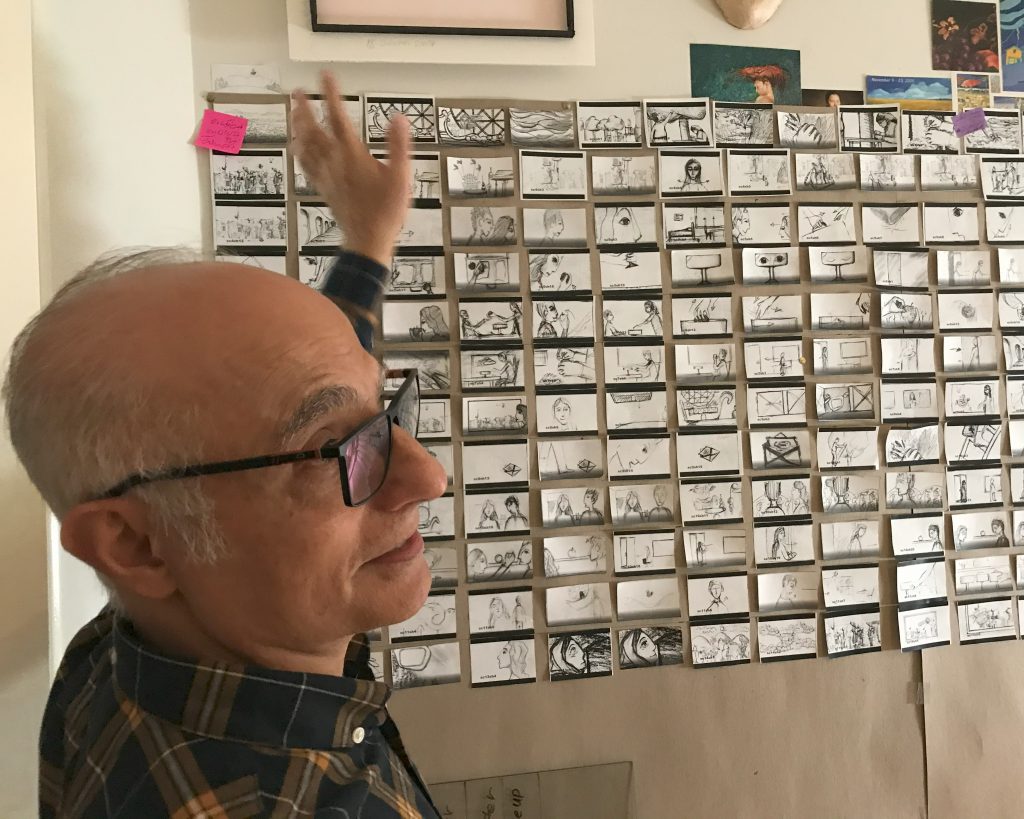

Excluding the time he spent working on the script or setting up the equipment and his special rig to capture each clay carving, Javahery estimates that it took about 18 months to film his nine-minute short, or roughly two months per minute.

Yet from the get-go, he was up to the task because the technique he chose to work in grew organically from the story.

“There was no logic; it was very emotional,” he said. “I always work like this. I like to go with my feelings.”

Clay itself is also central to the story. The protagonist in Two Apples makes zoetropes out of clay and uses them to give her dreams and ideas shape. Plus, the clay’s beige colour reminds Javahery of the general atmosphere of Kurdistan, the region in Iran he comes from.

“This colour is everywhere, in the hills and houses,” he said. “Now it’s found a new home. It’s immigrated with the girl in the story to a new country, where it will influence the culture there, and the new country’s culture will influence the girl.”

What equally lends the story so much of its emotional core is the Kurdish clove apple, the single item that the protagonist of Two Apples brings with her to the new country. These fragrant apples are studded with cloves, which preserve the fruit as it dries out. The clove apple is traditionally used to express strong emotions, like love or grief. In the film, the clove apple symbolizes the protagonist’s ties to both her family in the old world and her love interest in the new world.

A seasoned animation artist, Javahery is always experimenting with new techniques. Though he’s quite pleased with how audiences have reacted to Two Apples, he isn’t sure what medium he’ll use in his next film. That said, he can confirm it’ll start with the heart.

“I have ideas for the next work,” he said, “but the story will inspire the technique.”