The Forgotten Reels of Nunavut’s Super 8 Workshop: An Inuit School of Cinema

The Forgotten Reels of Nunavut’s Super 8 Workshop: An Inuit School of Cinema

When it comes to Indigenous filmmaking—defined here as films directed by Indigenous filmmakers—the National Film Board of Canada has been decades ahead of other national cinema institutions around the world. The NFB produced the first Indigenous non-fiction film, Ballad of Crowfoot (1968), by Willie Dunn;[i] the first Indigenous animated film, Charley Squash Goes to Town (1969), by Duke Redbird; the first Indigenous experimental film, Shaman (1973), by Mathew Joanasie; and the first Indigenous fiction film ever, For Angela (1993), by Nancy Trites Botkin and Daniel Prouty.

The recently unearthed collection of Super 8 films (see my previous blog posts, here and here), directed by Inuit filmmakers during the 1970s at a workshop in Frobisher Bay (today known as Iqaluit), Nunavut, further cements the NFB’s legacy as the world’s most significant producer of Indigenous cinema. It also establishes Nunavut as an epicentre of Indigenous filmmaking in the 20th century.

The collection, which was provided without credits or titles, can be divided into three general categories: school footage; travel footage; and arts, crafts and culture footage.

School Footage

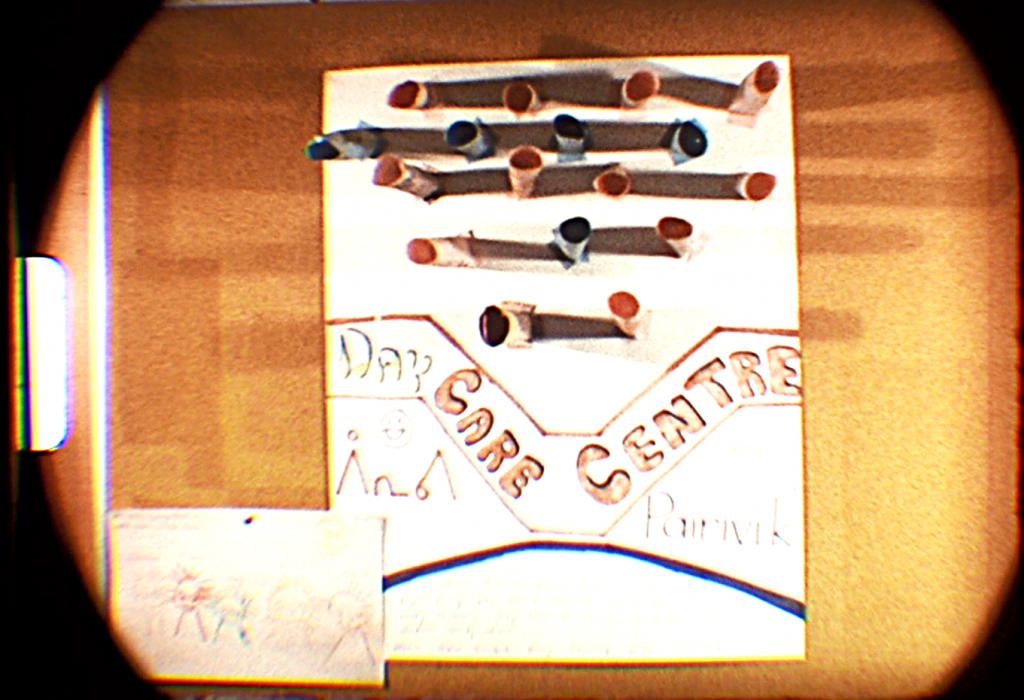

Less than six hours in this collection of reels contain footage focused on education and educational institutions. It includes scenes from daycare (see picture above), primary school, middle school and high school (perhaps shot in the Gordon Robertson Education Centre).[ii]

Also featured are shorts on a typing class, a carpentry course for adults, school libraries, interviews with teachers and staff, and after-school student support. One reel even portrays a family at home having dinner together after school. Additionally, the reels contain footage of skiing at a resort, which, in this context, appears to be another after-school activity.

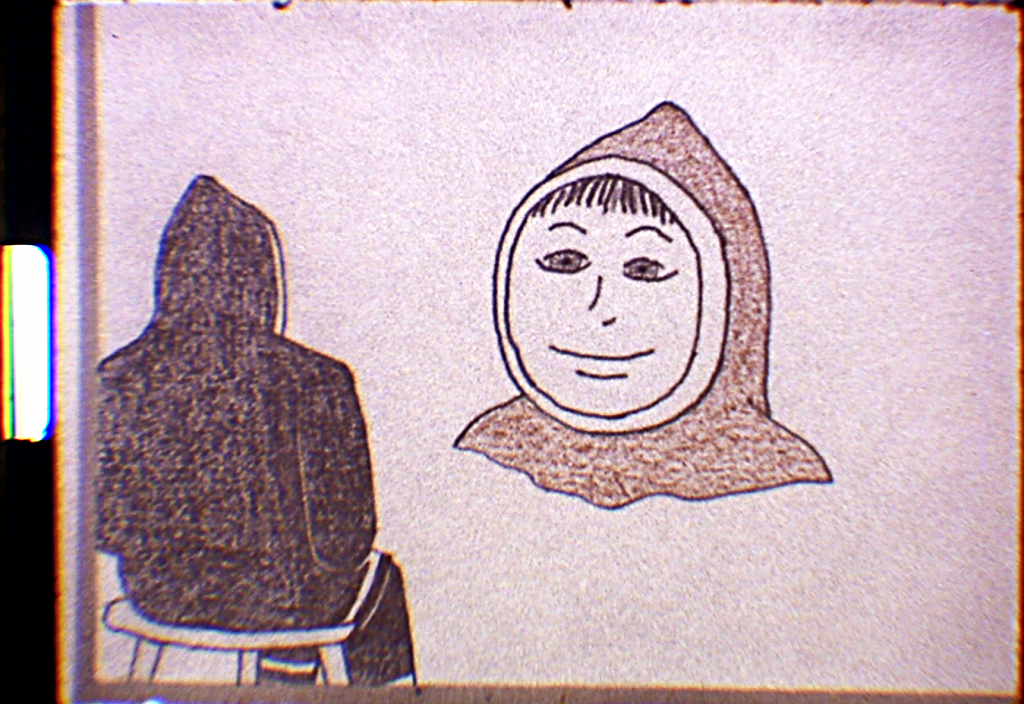

Some of this “school footage” concludes with an animated vignette featuring an Inuk who walks in, sits in front of a television and watches as the screen transforms into a face—perhaps his own. This vignette can be interpreted as a metaphor for the entire production: when Inuit watch this programming, it serves as a mirror.

Travel Footage

These reels contain approximately six hours and 30 minutes of footage documenting various journeys. The recorded sequences begin with an outdoor meal in a scenic natural setting, transition to a successful food-gathering expedition and continue with a fast boat ride to what appears to be a family visit at a nearby camp.

A separate, 12-minute segment features two boys playing and spending time together in the landscape. In one scene, the two friends are shown throwing pebbles at a rock. The footage follows them as they explore the area, sit by a lake to chat, and wade into the water.

The camera work in this segment is notably anticipatory and reactive, following the boys’ actions closely. This deliberate style could be interpreted as a fictional recreation, in which the filmmaker evokes a sense of childhood nostalgia, using the children as characters simply hanging out on an ordinary day.

The footage also highlights modes of transportation, the expansive landscape, Inuit camps, and everyday activities such as transporting goods, hunting, fishing and sharing meals. This footage is particularly notable for its stylistic approach. Unlike conventional films that use dynamic editing to construct a narrative, these reels parallel real time with screen time. This technique immerses the audience in the events as they unfold, fostering an acute awareness of their actual duration and the distances travelled, while shedding light on the daily lives of Inuit in Nunavut.

This footage offers a beautiful and unique insight into 1970s Nunavut, captured by masterful cinematography. The technical challenges involved were significant; for instance, hunting from a wave-tossed boat makes standing difficult, let alone recording stable footage with a Super 8 camera. Despite this, the collection includes nearly six hours of remarkable footage.

Arts, Crafts and Culture Footage

This collection of reels, totalling less than seven hours and 30 minutes, is primarily devoted to the artistic and cultural production of the Inuit community, a focus clearly prioritized by the filmmakers themselves. The footage encompasses a diverse range of content, including interviews with Inuit personalities and recordings of artistic performances.

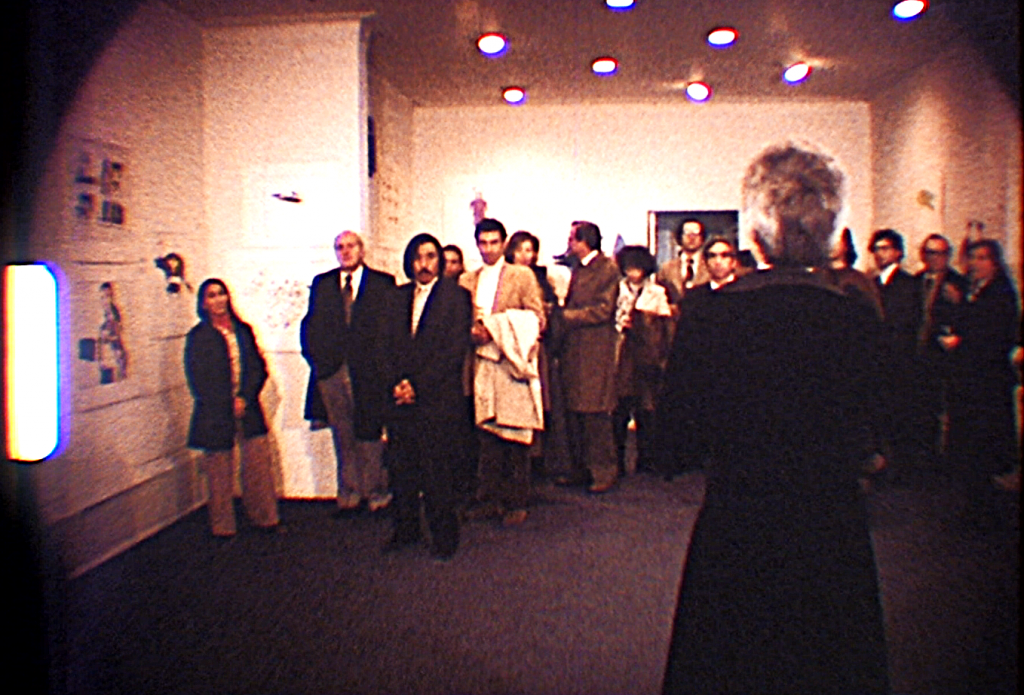

A significant portion is dedicated to documenting the visual arts. This includes hundreds of minutes shot inside artist cooperatives, with a particular focus on artisans at work and their finished crafts. Other segments capture an art exhibition in a gallery, a private household showcasing Inuit artwork, a feature on Inuit lithography, and textile artists within their studio environment. Further context is provided by footage shot inside a museum holding an Inuit art exhibition, which includes interviews with attendees.

The collection also contains pieces of significant artistic merit. One particularly interesting work employs deliberate zoom shots among city buildings; devoid of narrative, this reliance on pure camera movement frames it as an experimental film. Another meta-cinematic piece documents the process of recording Inuit musicians for a CBC broadcast, offering a self-reflective look at media creation.

A historically important segment is devoted to Frobisher Press, Ltd., the foundation for the iconic Nunatsiaq News (previously known as Inukshuk), which celebrated its 50th anniversary in 2023. [iii] The footage provides a valuable glimpse into the newspaper’s production process circa 1976, showing staff writing, illustrating, printing and delivering an edition.

Of particular interest is footage from an artistic co-op, featuring interviews with animators who worked between 1972 and 1975. For example, a super 8 reel profiles visual artists like Itee Pootoogook, in segments lasting over 52 minutes. Notably, Timmun Alariaq appears as the on-screen interviewer in many of these segments, solidifying his role as a central figure in Inuit cinema, alongside Salamonie Pootoogook and Mosha Michael.

A Priceless Cultural Heritage: Towards an Inuit School of Cinema

According to NFB files, the Frobisher Bay Super 8 Workshop (also referred to as the Nunaksiatmiut Workshop, which means “People from the Beautiful Land”) was a spacious, well-equipped facility. Thanks largely to NFB director/producer Wolf Koenig, it housed two VTR units in a mixing booth with monitors and a sound mixer, as well as projectors, screens, tape recorders, lighting equipment, blackboards, animation stands and extensive film and sound gear.

NFB files mention that in 1976, the Nunaksiatmiut Workshop produced content for their first six television programs, though no titles or credits are available yet. The team successfully met a CBC request for three programs by January 15, 1976. Crucially, it was agreed that same year that the recently formed Nunaksiatmiut Film Society would independently begin applying for government funding to continue its production. Also that year, Ann Hanson (the journalist, author and future Commissioner of Nunavut), gave a speech about Inuit pride in producing their own television programming, which aimed to improve everyday life by addressing topics like health, housing and education. She also discussed the expansion of CBC’s Northern Services Television and opportunities with Anik Info, noting that Nunaksiatmiut was interested in fulfilling these new programming slots. So it’s clear that the NFB’s workshop served to lay the groundwork for the Inuit production company that was subsequently formed, also called Nunaksiatmiut, which eventually fused with the Inuit Broadcasting Corporation in the 1980s.

The recent finding of these Inuit reels demands a fundamental rewriting of Indigenous cinema history. These Super 8 films, combined with the animation collection from the Sikusilarmiut Studio in Cape Dorset (see my blog posts here and here), comprise more than 90 animated, experimental, non-fiction and fiction Inuit films. These collections firmly establish Nunavut as arguably the most important hub of Indigenous filmmaking.

The sheer volume, consistent vision and historical depth of this work provide undeniable evidence of a distinct Inuit school of cinema. Hopefully this unique collection of films—which present Nunavut as a modern, sophisticated and complex society—will become available in other languages soon, so that they can be shown worldwide. These collections encompass living expressions, traditions and knowledge—treasures that serve as time capsules for an entire nation. In short, they constitute a priceless cultural heritage, with historical and cultural importance equal to Château Frontenac or Niagara Falls!

This National Day for Truth and Reconciliation, the NFB invites you to visit our channel Inuit Cinema at the NFB, and you can also watch hundreds of films free of charge on our Indigenous Cinema channel, here.

I’ve always been a fan of the NFB, and the more I work here and discover its films and its history, the more my respect deepens for the artists who’ve created the many gems in the NFB’s film collection.

Enjoy!

[i] Although for some researchers the first Indigenous filmmaker is—presumably—James Young Deer, his identity is still not confirmed; see: https://www.theguardian.com/film/2010/sep/23/first-native-american-director

[ii] Gordon Robertson Education Centre

[iii] https://nunatsiaq.com/stories/article/yesterdays-news-it-all-starts-with-inukshuk/