Lunch with Colin Low

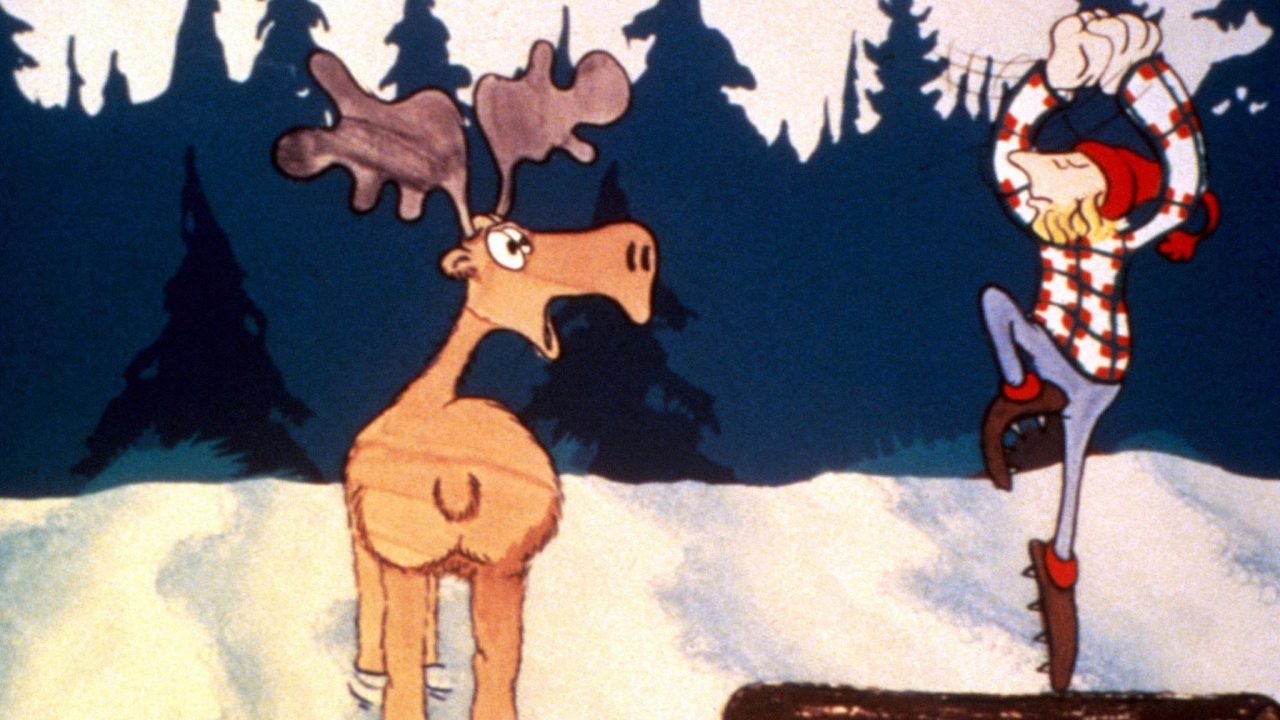

The Children of Fogo Island, Colin Low, provided by the National Film Board of Canada

The NFB, in partnership with the Shorefast Foundation, will soon launch an e-cinema on the Atlantic island of Fogo, northeast of Newfoundland. An all-digital community theatre, the Fogo Island Film House will screen films from the NFB’s expanding digitized films collection, including a unique series of 27 films that were shot on the island some 40 years ago.

The Film House will be the first theatre ever to exist on the island, and the first English language e-cinema in Canada.

Someone who cares deeply about the struggles and joys of the people of Fogo Island, and will be attending the cinema’s official opening, is Colin Low, the man who directed the Fogo films as part of the NFB’s Challenge for Change program, in the late 1960s.

Colin Low also happens to be my neighbour, here in Montreal. When it was decided I should meet him to chat about his work on Fogo and his thoughts on the recent e-cinema initiative, he graciously invited me to join him and his lovely wife Eugénie for lunch.

It isn’t everyday one gets invited for lunch by an Oscar-nominated filmmaker, who was among the founders of IMAX, and an inspiration to Stanley Kubrick.

I said yes.

It was a lovely visit that stretched well after lunch into several pots of good tea. We talked about Fogo, of course, but also about all the different people, places and films that converged to bring Colin Low to the island, in that fateful summer of 1967 where he shot a series of film that would not only change the way in which a remote, heavily unemployed community perceived itself and its prospects, but also established the medium of film as a tool that could be used to bring about measurable social change, anywhere in the world.

Throughout our conversation, what struck me more than anything was the deep love and curiosity Low feels for all people. Even in his early films, like Circle of the Sun, about Alberta’s Blood Indians, or The Hutterites, his approach is always humble and respectful; descriptive more than prescriptive. His documentaries seem to be less what he thinks than what he sees. And that is rare.

Low says that all that happened in Fogo was the result of him lucking into a group of “profoundly amicable” people.

It all started when NFB producer John Kemeny took Colin Low out for lunch and asked him what he knew about poverty. Low had just finished working on the In the Labyrinth, the stunning piece the NFB would be presenting at Expo 67 in Montreal. Before he knew it, Kemeny was asking him whether he’d be interested in going to Newfoundland.

“’Well, yes, I thought’”, Colin told me, “”that would be a nice way to spend the summer!’”

“I’d always wanted to go there and enjoyed the thought of being away from the Expo and the theatre for the summer.”

And so he went, bringing his wife Eugénie and their son Alex, who was 5 at the time, along for the ride.

In Saint John’s, Low met with Donald Snowden, then Director of the Extension Department at the Memorial University of Newfoundland and Fred Earle, who was from Fogo and worked as the university’s Fogo Island field officer.

Snowden first suggested that Low visit a few resettlements on the main island of Newfoundland where remote, economically distressed communities had been relocated in an attempt to revive them. Both in terms of characters and stories, Low didn’t find what he was looking for. It was then that Snowden told Low that in that case, he’d probably have to go to Fogo.

As Low tells it, Fogo had “once been a good-looking place but it was no longer”. With the fisheries gone and unemployment high, the energy had run out. In those days, across Fogo’s 7 distinct communities, 60 percent of people were without a job.

“People were angry”, Low says. “And not the energetic kind of angry either. There was a lot of apathy.”

Yet through contacts he made on the island – Randy Coffin, whom Low hired to help him to select interviewees, and the Rowbottoms, with whom Low and his family lived, in Joe Batt’s Arm – the documentary maker started to tap into the combativeness and resilience of Fogo’s people. And he started filming and talking to people, and filming some more.

All in all, 27 documentaries where made. In one film, Billy Crane Moves Away, fisherman Billy Crane speaks frankly about the state of the fisheries and how the lack of government support has led to the industry’s downfall. He’s moving to Toronto, and is saddened by the move, but he believes he doesn’t have a choice. In another, citizens discuss their efforts to establish a co-op.

By Low’s own admission, the result isn’t action-packed blockbusters. “They’re not powerful films,” he says. “There’s no outside conflict in them.”

As Eugénie explained, stepping into the living room with a tray of delicious brownies, “the film is what they used to solve the conflict”. “

“Now, the Fogo process is THE process for solving conflict,” she said, in a way that hinted at just how proud she was of her husband of 60 years.

“It’s not about dramatizing and illustrating conflict superficially, for the entertainment of others. It’s about working on it for ourselves.”

Yet beyond Low’s almost ethnological interest in Fogo’s community issues and dynamics, the groundbreaking feature of all the Fogo films is that Low involved everybody that had been filmed into the editing process. Everyone.

“It really helped build confidence,” Low says. “We had rough cuts of all the footage and this great, two-track Siemens projector that separated the sound and the image. We’d have community showings and at any time people could jump in and ask us to edit something out. You could edit one or the other. Change the sound and keep the sound, or vice-versa.”

It turns out nobody ever asked Low to edit anything out. The process, however, had the impact of affirming Low’s integrity and desire to “get it right,” to tell the story the way they wanted it told, from their perspective.

And there was probably more to it, too. Involving the citizens of Fogo in the editing process like Low did forced the community members to face each other and themselves. In some ways, the power of such an approach has much in common with talk therapy. It rests, to a large extent, on the dual benefits of actively being listened and paid attention to, while also hearing one’s self spell out concerns, fears and grievances out loud.

In his own way, Colin Low gave the people of Fogo both a voice, and an ear. And when he involved the islanders in the editing process, he also gave them a mirror to take a good long look at themselves.

From then on, in the years that followed, it was all a virtuous cycle upward on Fogo Island. The fishers formed the Fogo Island Co-operative Society, a community based enterprise on which they built the economy of the island. They built more boats. They built bigger boats. They took over processing facilities abandoned by private enterprise, built more plants and sought new markets. And Fogo didn’t only survive, it thrived.

To hear Colin Low talk about it, you can’t help but be amazed by what an inspired creative mind moved by genuine love for people can achieve.

Opening night is June 1st, at the Fogo Island Film House. The theatre will screen one of Colin’s favorite film of the series, The Children of Fogo Island.

Local residents who appeared in that and other Fogo Island films will be in attendance and there is much to bet it will be a night a night to remember.

What an inspiration! We should do it again (Challenge For Change)! I wish I could play a harp or stepdance like that!

LOVED this!!!!