A doc by any other name: explore 4 types of documentary films

A doc by any other name: explore 4 types of documentary films

Did you know that NFB.ca offers over 2500 films you can watch online? And that’s only a fraction of the 13,000+ productions the NFB has made since we started out in 1939! It’s safe to say that many (if not most) of these films are documentaries, because our mandate has always been to represent Canada and Canadian social issues to both domestic and global audiences.

But documentary film isn’t just one singular beast—there are lots of types of documentary films out there, and just as many approaches to the artform by documentary filmmakers. Want to learn more about the different kinds of docs there are? Read on, and watch a few examples of each type to help you get the idea…

Expository docs: the who, what, when, where, and why

An expository doc is probably what you picture when you imagine what a documentary is. These films:

- address the audience directly and aim to present the appearance of reality.

- often use authoritative, “objective” narrators or titles to guide viewers and to interpret what we are watching.

- often use archival photographs, film and original documents to present historical events.

- present information and try to prove a case or persuade viewers of an interpretation of reality.

- may employ “docu-drama” sequences or re-enactments of historical events in order to fill in the holes of the documentary footage already shot.

A great example of this type of film is 1949’s City of Gold, which depicts the Klondike gold rush at its peak.

City of Gold, Colin Low et Wolf Koenig, offert par l’Office national du film du Canada

When you see a film like this, you’re meant to leave feeling as though you fully understand the “truth” of a history, a situation, or a person. This is, however, why expository documentaries are often criticized—they seem to present an unproblematic and often one-sided point of view of otherwise complex issues.

For another example of an expository doc on NFB.ca, check out Action: The October Crisis, which profiles the 1970 FLQ crisis in Quebec.

Observational documentaries: reality plays itself

Many filmmakers and audiences found the “voice of God” approach used in the expository documentary to be a bit bossy and one-sided. Alternatively, it was thought that the distance between audience and film could be directly bridged without a narrator. Could events simply be shot and then speak for themselves?

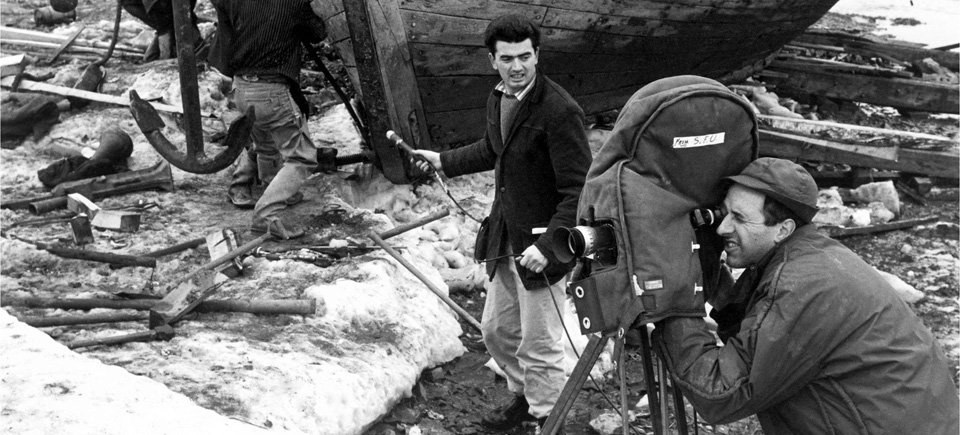

In the 1960s, the cinéma vérité style of observational filmmaking gained traction. These types of films:

- used portable equipment (which was a new thing in the 1950s) to put the filmmaker “in the thick of things” as events unfolded. (As Michael Moore recently observed, this portable equipment “allowed people like me to run from the police!”)

- attempted to let a variety of people on all sides of an issue speak candidly for themselves.

- recognized the role of the filmmaker as having some influence over the content, but aimed to keep that influence to a minimum.

- believed that filmmaking technology and film language could effect social or political change, thereby using documentary as a tool for activism.

Lonely Boy (1962) is an absolutely delightful and charming example of observational documentary. We follow the young teen idol Paul Anka as he hits the road and plays sold-out concerts to crowds of screaming adolescent girls. But all throughout, we are left to draw our own conclusions about the crazy world of show business as Paul talks candidly between performances.

Lonely Boy, Wolf Koenig et Roman Kroitor, offert par l’Office national du film du Canada

You can read more about Lonely Boy in this blog post. Want to check out a couple more observational docs? Take a look at Billy Crane Moves Away (1960), a portrait of a migrating fisherman that addresses the changing face of agricultural labour, or The Back-Breaking Leaf (1959), a film that was voted among 15 must-watch documentaries by The Globe and Mail.

Reflexive and participatory documentaries: if a tree falls in the forest…

All filmmaking arranges and manipulates the illusion of reality, no matter how much it may try not to. Reflexive and participatory filmmaking exposes the filmmaker, his/her character and opinions, and even the process of filming itself. (Michael Moore often uses this approach in his films, usually with a heavy dose of expository elements).

Reflexive docs are often defined by these characteristics:

- the film itself is constructed around the making of the film, including the filmmaker’s research and pursuit of knowledge.

- the film and filmmaker are highly skeptical of “realism”.

- the filmmaker’s relationships with the subjects s/he films change the nature of the story being filmed.

A great example of this type of doc is Sarah Polley’s acclaimed feature Stories We Tell (2012), which is available as a digital download and on DVD. You can watch the trailer here. This film can be classified as a first-person documentary, a sub-set of the reflexive/participatory genre in which a filmmaker uses the medium to examine his/her own situation for the purpose of self-revelation and self-discovery. In this case, documentary can almost be understood as a therapeutic tool, one which reveals surprises to both the audience and the filmmakers themselves.

For another thought-provoking example of a participatory doc, check out Waiting for Fidel (1974), in which a group of 3 ambitious Canadians attempt to get Fidel Castro to appear in their film. But the film itself reflects more about its creators than about any “objective” political reality of the time.

Waiting for Fidel, Michael Rubbo, offert par l’Office national du film du Canada

Poetic documentaries: an intuitive experience of the world

In these films, the focus is less on facts and more on experiences, images, and seeing the world with new eyes. These films:

- present images out of context, and with enhanced effects such as colouring, editing, or speeding up/slowing down footage.

- are unconventional and/or experimental in both their form and content; they do not rely on standard filmmaking and film language tropes.

- attempt to create a feeling rather than a truth.

For example, check out this clip from 2011’s Hard Light, a beautiful film based on the experiences of Newfoundlanders across generations, as profiled in the poetry of writer Michael Crummey.

I am someone who has always been interested in film, and always wanting to learn more about it. It’s cool to know that when it comes to observational documentaries, that when it comes to the topic it allows people speak on all sides about it freely. That is something that I think would help make a really good documentary, and it helps with expanding people’s minds on the subject.

Had to read and discuss “Under the Volcano”, in Graduate School in the States long ago. Most of the other writers were young American authors, but several English writers were included such as Iris Murdock. Over the years I tried to keep up with what the authors that we studied were writing. Very difficult task for a Canadian studying in the states.

I think if I were still teaching grade 12 English, I would chuck the whole bunch and set out the course and have the class read nothing but Patrick O’Brian’s novels. O.K., just kidding. But those would keep the boys interested.

Last book I read of Malcolm’s was his Last Novel–October Ferry to Gabriola.

My wife bought the novel for $0.99 years ago when she found it in a local bookstore in Nanaimo, B.C.,on Vancouver Island, just off the island of Gabriola!

Cheers,

Doug

Hi Doug, indeed we do have a rich history of wonderful literature in this country. I bought my copy of “Volcano” for $0.69 at a used book sale! Lowry was a truly unique writer. Thanks for your comment. – Jovana