McLaren in Times Square, New York

McLaren in Times Square, New York

This post is a translation of a post that originally appeared on our French blog. You can read the original here.

In the early 1960s, Norman McLaren was assigned an unusual project: the production of a promotional film about Canada to be shown on a billboard in Times Square, New York.

The request came from the Canadian Government Travel Bureau, who had rented a giant sign at the corner of Broadway and 46th St. for a period of 13 weeks in the summer of 1961. The idea was to project a film promoting Canada as a tourist destination.

The final product turned out to be a silent, frame-by-frame short animation that ran 8 minutes. Norman McLaren‘s team on the project included Kaj Pindal, Ron Tunis, and René Jodoin, with Arthur Lipsett at the editing table.

First called Welcome to Canada, the film was later renamed New York Lightboard when a slightly abridged version was finally completed.

New York Lightboard, Norman McLaren, provided by the National Film Board of Canada

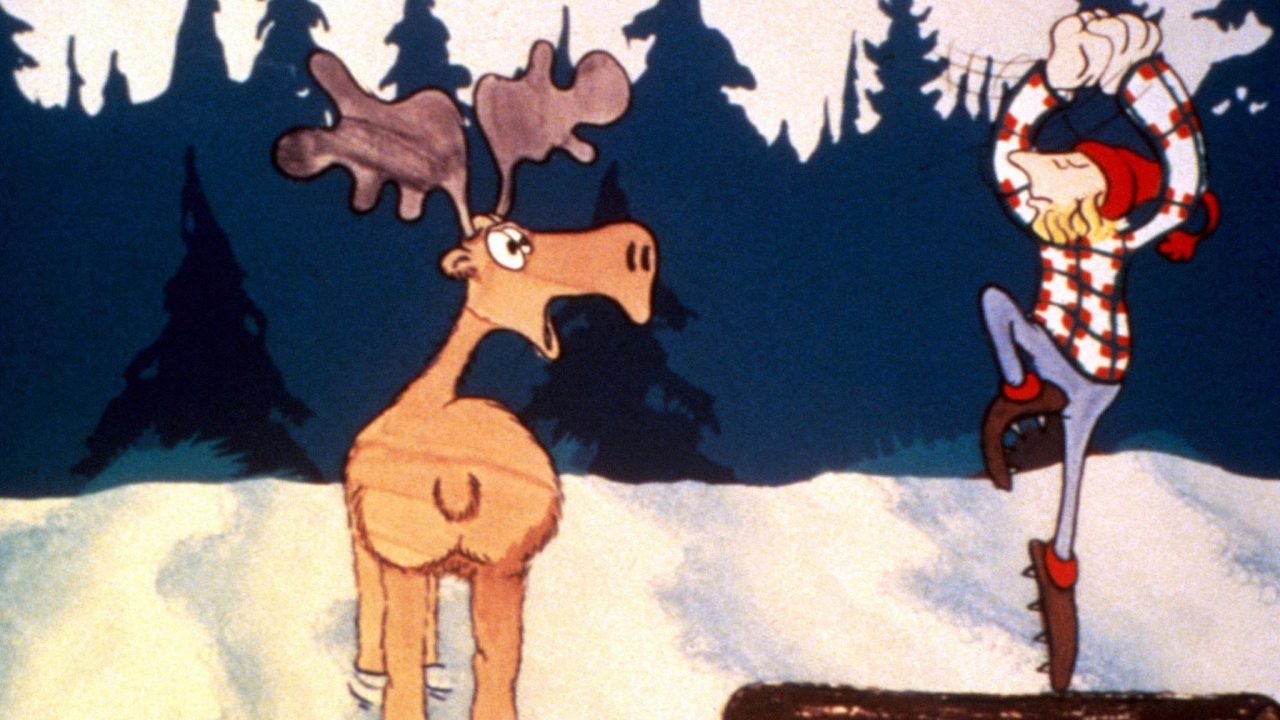

True to the spirit of McLaren’s work (he was already an internationally acclaimed artist at the time), the film is made up of flashing slogans, phrases, and animated shapes created through the use of paper cutout and hand-drawn animation techniques. It promotes the attractions of the country: the Montreal Jazz Festival, the Calgary Stampede, winter sports, the Canadian Rockies, and more. At the end of the film, we even see McLaren’s signature tongue-in-cheek humour: “Stop looking at this sign and come to Canada”.

A Spectacular Sign

A Spectacular Sign

At a size of 30 × 32 feet, the lively Epok electronic sign was distinguished by its unique photoelectric lighting system, which facilitated the projection of animated scenes on a surface of 720 square feet equipped with 4104 bulbs. The bulbs were lit by photoelectric cells that responded to the light passing through the film stock as it unspooled.

A Visit to the Big Apple

Before beginning work on the project, McLaren and Jodoin went to Times Square to take a closer look at the billboard on which their film was to be projected. Upon their return, McLaren asserted the need for the promotional film to have something “humorous or with human interest” in it in order to stand out from other billboards and attract the attention of passersby.

“The dullest thing is when something is absolutely still. Even a simple word loses its interest when it is stopped. We did develop a new technique but found that going back to my old technique of drawing directly on film gave the best results.” – Norman McLaren

Although the process required three and a half months of work and thousands of drawings, McLaren found the production much more enjoyable than that of many of his other films, since it had “no problems, no colour, no sounds.” Instead of a soundtrack, the film borrowed the thunderous atmosphere and constant bustle of New York.

Once the film was finally displayed in the summer of 1961, McLaren returned once again to the city that never sleeps in order to shoot this short documentary:

New York Lightboard Record, Norman McLaren, provided by the National Film Board of Canada

In 1960, it was estimated that nearly one million people visited Times Square every day. Although this figure may seem high, it’s still safe to say that McLaren’s film was seen by millions of Americans and foreign tourists that summer, particularly since it was projected in a daily loop from dawn until the wee hours of the morning.

As the Montreal-Matin newspaper so aptly put it in an article dated July 7, 1961: “If New Yorkers and the millions of Americans who visit the American metropolis are afterwards not familiar with the attractions of Canada, it will certainly not be the fault of the Canadian Government Travel Bureau.”

Indeed, the project was very ambitious, especially at that time. Today’s Canadian Tourism Commission might not even be able to mount such an ambitious campaign!