* This post is a translation. Read the original French post here.

Though in use since the 1930s, the Alexeïeff-Parker pinscreen remains an enigmatic figure within the animation world.

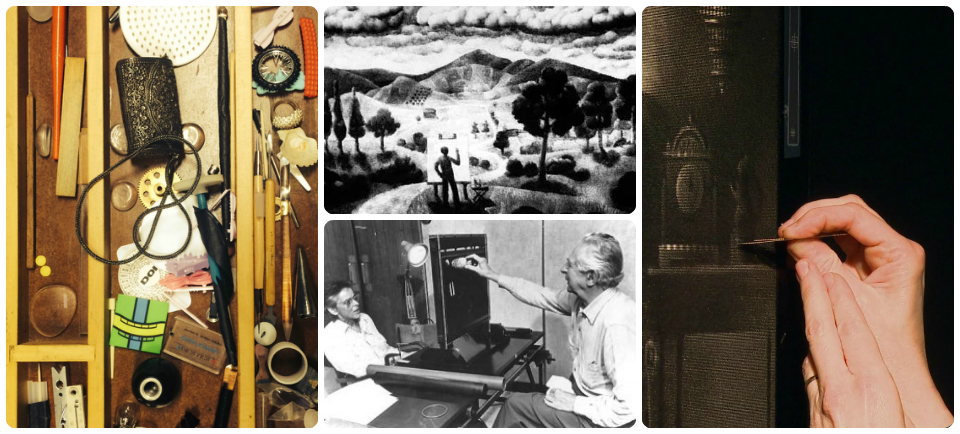

An upright board pierced with hundreds of thousands of holes, each with a black retractable pin through it, the pinscreen is used vertically, in complete darkness. It is lit obliquely so that the pins, based on their depth, can project every tone from black to white.

To make a film, the animator pushes in groups of pins using various small instruments, to form an embossed design. Next, he takes a photo, and then modifies his design slightly before taking another photo, and so on. To make a single second of animation, 24 of these photos are required.

Although the method, which requires meticulousness, ambidexterity and detachment, is not for every animator, and its product, which is more dreamlike and hazy than narrative and precise, isn’t right for every story, anyone can learn about pinscreen animation and fully appreciate it. Here are 3 keys.

1. Pinscreen animation is engraving in motion

Before inventing the pinscreen with his second wife, American artist Claire Parker, Alexandre Alexeïeff had earned a reputation for his brilliant engravings. Born in Russia, he arrived in Paris in the early 1920s and worked in the rare books and fine editions industry. He illustrated numerous collections of poems and stories, notably including a three-volume work The Brothers Karamazov by Dostoyevsky and The Queen of Spades, a short story by Pushkin. For Alexeïeff, the pinscreen was conceived of as a practical means to articulate engraving, to set it in motion.

By seeking to animate the engraved image, with its blacks, whites and infinite shades in between, Alexeïeff wished to explore the more artistic counterpart of animation. The instrument, as well as the films that stemmed from it, attest to this desire to move away from cartoons, which were at the time very focused on line precision, speed and buffoonery (consider for example the early days of the Walt Disney empire) to create something else: a more serious animated film, a more “fine art” product.

2. Pinscreen animation springs from the French first avant-garde

First avant-garde (sometimes called French Impressionist cinema) refers to films in which the visual language dominates the subject. This first avant-garde, typical of the early 1920s, is marked by striking works, often veritable visual symphonies in which the graphic possibilities of the medium (framing, rhythm, movement, lightness and darkness) are used to the fullest.

This primacy of image is combined with a great focus on the realm of the subconcious. The results are evocative, dramatic and poetic works in which symbols, dreams and desires meld together. The action is more often shaped by the fluctuations of a piece of music than by the unfolding of a given story. Alexeïeff’s very first films, for example A Night on Bald Mountain, attest to the influence of this current in the genesis of the medium.

3. The pinscreen is one of the rarest instruments in all of animation

For many years, pinscreen inventors Alexandre Alexeïeff and Claire Parker were the only ones in the world who used it. Their first films were well received, but people quickly realized that the process was time-consuming and thus expensive. None of the large studios showed serious interest in their invention… except for the National Film Board of Canada.

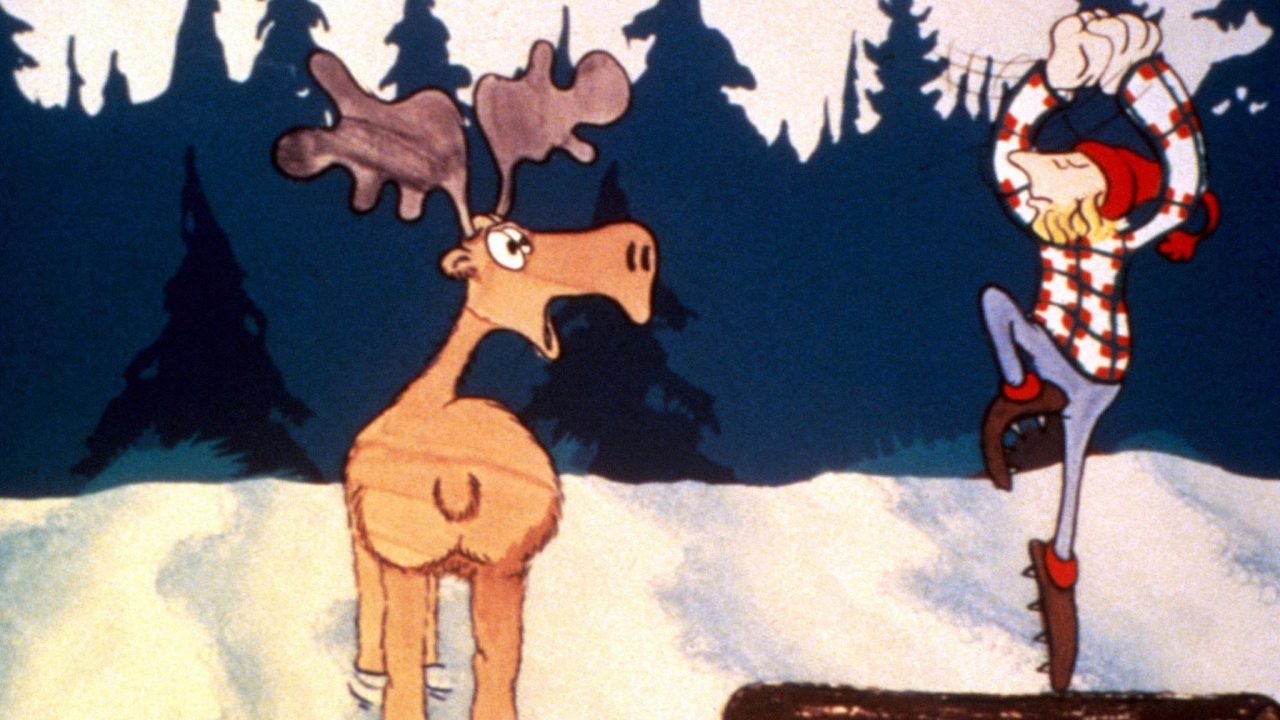

Alexeïeff and Parker were invited to the NFB for the first time by Norman McLaren in 1944. McLaren was tasked with founding an animation studio and wanted to bring in foreign animators. The short film En passant [In passing], which would open of the Cannes Film Festival in 1946, was the product of this first meeting between the pinscreen and the NFB. It was not until 1972 that this union was revived again. Through McLaren, the NFB had acquired a pinscreen and asked Alexeïeff and Parker to give a workshop to its animators at that time, including Ryan Larkin and Caroline Leaf.

However, it was Jacques Drouin, a Quebecker student freshly returned from the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), who would ask McLaren to use the screen. Drouin had seen the film by Alexeïeff and Parker entitled Le Nez [The Nose] (1963) at the famous Museum of Modern Art in New York (MoMA). This brilliant 10-minute film, based on a short story by Gogol, would prove to be the inception of a long and productive career in pinscreen animation. For three decades and right until his retirement, Jacques Drouin was the only person in the world to use the screen.

Today, illustrator Michèle Lemieux has taken up working with the pins. For the first time, a woman is alone at the helm. In 2012, she produced Here and the Great Elsewhere, and she started production on a second film (working title Illusion; currently in production) in which she wants to roll back the limits of the medium by filming both sides of the screen, thereby using both the positive and negative side of the image, and by playing with and around the screen (projection of shadows on the wall, juxtaposition of objects on the screen, etc.).

At the same time, Michèle Lemieux connected with Svetlana Alexeïeff-Rockwell (who died last January 15 at the age of 91), a painter and the sole descendant of Alexeïeff. Svetlana was the product of Alexeïeff’s first mariage and helped develop, alongside her mother Alexandra Grinevsky, the first prototype of the pinscreen. When she first screened Michèle Lemieux’s film, she was moved to tears.

Here and the Great Elsewhere, Michèle Lemieux, provided by the National Film Board of Canada

Together, the 2 women arranged for the repair and restoration of a second pinscreen, called Épinette, the “twin” of the one used by the NFB. In 2012, it was sold to the Centre national du cinéma et de l’image animée (CNC), in Paris, which intends to make the tool available for European artists to create new animated works. Michèle Lemieux will soon head to France to give, as Alexandre Alexeïeff, Claire Parker and Jacques Drouin have done before her, a master class in the hopes of sparking curiosity, even perhaps love at first sight, just like she felt for this very special instrument.

* View our selection of films The NFB celebrates pinscreen animation, launched to mark the passing of Svetlana Alexeïeff-Rockwell.

* This post was written in part using information gathered from Julie Roy, executive producer of the NFB’s French animation studio.