Inventing a Tradition: Arthur Lipsett and the NFB’s “Studio X”

Inventing a Tradition: Arthur Lipsett and the NFB’s “Studio X”

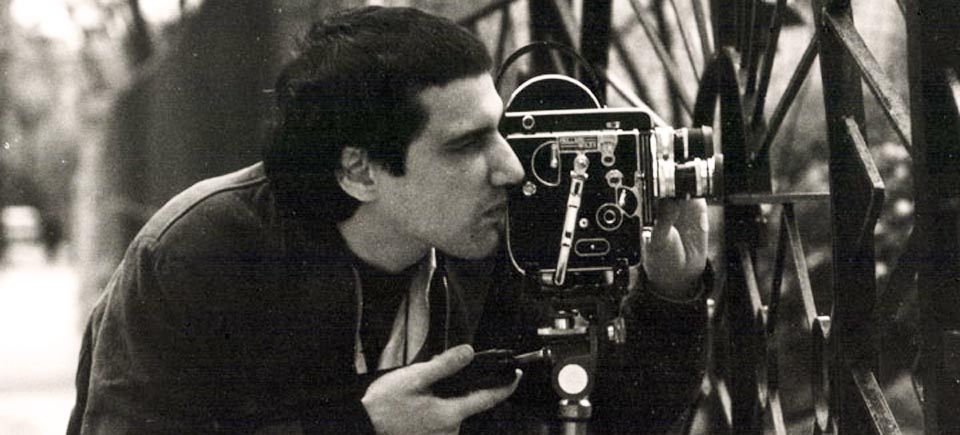

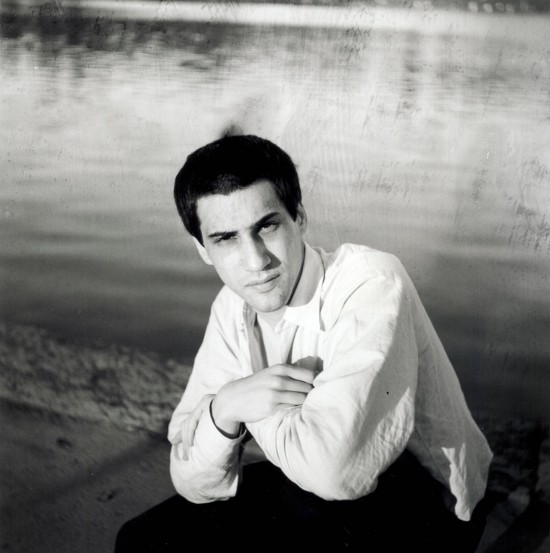

In honour of Arthur Lipsett’s birthday (May 13, 1936) we’ve invited filmmaker, writer, and editor Brett Kashmere to talk about Lipsett’s films and the history of experimental cinema at the NFB in the 60s and 70s.

The National Film Board is famous for its influential contributions to the evolution of documentary cinema in the decades following World War II. But less known is the burst of experimental film activity that it kindled throughout the 1960s and ‘70s.

A catalyzing factor was the integrative, exploratory, creative environment of its acclaimed Unit B, which fostered a team of bright young recruits – artists, writers, animators, producers – under one multitasked aegis. The Unit B notably helped redefine nonfiction practice, ushering in a wave of modern, intimate, and ambiguous perspectives on daily life. Its films were also marked by a newfound attention to aesthetic quality and technical innovation. Although the unit system was dismantled in 1964, a paradigm for experimentation was established that would persist through the free-spirited ‘70s. The films of Arthur Lipsett in particular map and articulate many of the new artistic, hybrid, and expanded cinematic forms and points of focus that emerged during this fertile and unconstrained moment.

Cut, Copy, Paste: Origins of the Canadian Collage Film

When Lipsett, fresh out of Montreal art school, was hired to work in the Unit B’s animation department in 1958, an independent avant-garde cinema did not exist in Canada. In the absence of tradition, Lipsett blazed a new trail. His pioneering collage films imparted exciting possibilities for handcrafted, personal, cameraless, and found footage filmmaking, both in his time and in the present day.

Very Nice, Very Nice, Arthur Lipsett, provided by the National Film Board of Canada

Lipsett’s first film, Very Nice, Very Nice (1961) began modestly as an audio editing exercise, pieced together from discarded sound bits. It was later expanded and illustrated with candid self-shot street photos, clipped magazine images, and stock footage. The film received a 1962 Academy Award nomination in the Best Live Action Short category, was broadcast on national television, screened in New York arthouse cinemas (as an opener to Luis Buñuel’s Viridiana [1961]), and traveled the world; providing instant recognition and temporary “boy wonder” status both within and outside of the NFB.

Stanley Kubrick and George Lucas, for instance, were two of the film’s early admirers. It also introduced a new genre into Canadian cinema: the collage film. Like all of Lipsett’s films, Very Nice, Very Nice disrupts the representational value of documentary image and sound, moving beyond the genre’s (and the NFB’s) aesthetic codes of truth and reliability, such as “voice-of-god” narration. The result is a sardonic re-coding of 1950s consumerism and mass media. Images of the horrific and often overlooked damage left by both war and technological progress punctuate Very Nice, Very Nice, resulting in a film with enduring impact.

Stanley Kubrick and George Lucas, for instance, were two of the film’s early admirers. It also introduced a new genre into Canadian cinema: the collage film. Like all of Lipsett’s films, Very Nice, Very Nice disrupts the representational value of documentary image and sound, moving beyond the genre’s (and the NFB’s) aesthetic codes of truth and reliability, such as “voice-of-god” narration. The result is a sardonic re-coding of 1950s consumerism and mass media. Images of the horrific and often overlooked damage left by both war and technological progress punctuate Very Nice, Very Nice, resulting in a film with enduring impact.

City as Subject: The Urban Environment Reimagined

In 1962, Lipsett contributed footage to the lyrical, slice-of-daily-life documentary, September Five at Saint-Henri (Hubert Aquin, 1962). The film exemplifies the “candid eye,” cinéma direct form that emerged from the Unit B and l’équipe française in the late-50s and early-60s.

Harnessing the unique talents of both rosters, September Five assembles images from 28 camerapersons into a sunrise-to-sunset, cinéma vérité portrait of one working class neighborhood on the first day of school. Attention to the lives and concerns of the city’s citizens and communities would become a defining characteristic of the NFB’s most daring and novel creative initiatives throughout the 1960s, including the activist “Challenge for Change” series.

September Five at Saint-Henri, Hubert Aquin, provided by the National Film Board of Canada

The city as subject found expression in various new approaches to the nonfiction form during this period. The Devil’s Toy (Claude Jutra, 1966), a dry humored, visually elegant pseudo-documentary about youth culture and the rising skateboarding “nuisance,” weaves effortlessly through Montreal’s expansive park spaces and hillside boroughs.

The Devil’s Toy, Claude Jutra, provided by the National Film Board of Canada

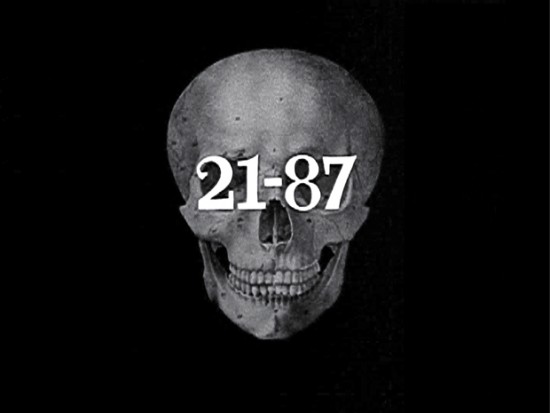

23 Skidoo (Julian Biggs, 1964), on the other hand, reflects the nuclear anxiety of the era, offering a stark, unsettling depiction of a downtown Montreal landscape devoid of human presence. 21–87 (Arthur Lipsett, 1964) is likewise filled with dystopian symbolism – from the opening image of a skull, to soulless, automated assembly lines, a charred corpse, and a robot mime. Described as “A wry commentary on machine-dominated man,” the film conveys Lipsett’s pointed, satirical wit as well as his concern for an increasingly dehu manized civilization.

21-87 concludes with “a good-hearted friendly voice” repeating a line from earlier in the film, which connotes Lipsett’s view that social conformity creates mindless, happy masses: “Somebody walks up and you say, ‘Your number is 21-87, isn’t it?’ Boy does that person really smile.” One of his most successful pieces, 21-87 received, among other accolades, Second Prize at the 1964 Palo Alto Film-Makers Festival in California, where Kenneth Anger’s Scorpio Rising (1962) and Bruce Conner’s Cosmic Ray (1963) finished first and third respectively. Although Lipsett’s films were not widely known to American audiences at the time, being recognized alongside two of the heavyweights of underground cinema confirmed Lipsett’s place within the avant-garde canon.

21-87, Arthur Lipsett, provided by the National Film Board of Canada

Drawn to Abstraction: Experimental Animation

Perhaps the most impressive strain of ostensibly avant-garde cinema to flourish at the NFB during the 1950s and ‘60s was experimental animation. Norman McLaren’s direct animation work was synonymous with the Board’s emergent, mid-century artistic identity and influenced subsequent generations of filmmakers, including Lipsett himself, who began his career as an apprentice to McLaren. Among Lipset’s first film credits was as assistant director for McLaren’s whimsical, stop motion Opening Speech (1961).

Opening Speech: McLaren, Norman McLaren, provided by the National Film Board of Canada

The fluid, fast-paced rhythm of the swinging, handpainted Begone Dull Care (Evelyn Lambart and Norman McLaren with music by Oscar Peterson, 1949) and the ecstasy of the engraved Blinkity Blank (Norman McLaren, 1955) are defining features of Lipsett’s Free Fall (1964). Free Fall features dazzling pixilation, in-camera superimpositions, percussive music, syncopation, and ironic juxtapositions. Using a brisk single-framing technique, Lipsett attempts to create a synaesthetic experience through the intensification of image and sound. Citing the film theorist Siegfried Kracauer, Lipsett wrote, “Throughout this psychophysical reality, inner and outer events intermingle and fuse with each other – ‘I cannot tell whether I am seeing or hearing – I feel taste, and smell sound – it’s all one – I myself am the tone.’” Sensory overlap is a key aspect of “visual music,” another established idiom of experimental animation that is well represented in the NFB library.

Begone Dull Care , Norman McLaren & Evelyn Lambart, provided by the National Film Board of Canada

Free Fall, Arthur Lipsett, provided by the National Film Board of Canada

More than any other filmmaker, Lipsett welded the NFB’s documentary obligation with the experimental impulses permeating its Unit B. His found footage masterpiece, the newsreel remix A Trip Down Memory Lane (1965) slyly straddles both traditions.

A Trip Down Memory Lane, Arthur Lipsett, provided by the National Film Board of Canada

The notion of a government-sponsored avant-garde cinema is itself antithetical, but Arthur Lipsett’s incandescent arc of films is proof that challenging, even radical, art can seed and flourish, at least temporarily, within an institutional context. Although he only completed a small body of work over a relatively brief stretch of time there – six films in 10 years – his influence on the course of experimental film at the Board and beyond was profound. Lipsett’s filmmaking opened new directions and possibilities for his generation and those that came after. Extending upon his applications of vertical montage (the moment-to-moment juxtaposition of picture and sound), the Canadian film artists that followed Lipsett, whose work was taught in classrooms across the country and shown on the CBC, is marked by greater formal manipulation and layering, combined with, in some cases, personal, poetic, and emotional subject matter. Seen in this context, Lipsett’s contributions to the NFB’s experimental film history – the notional “Studio X” – assume ever richer, more abundant meanings.

🎬 Visit Arthur Lipsett’s director page on nfb.ca here.

Lots o’ good info in a small space! Ties a lot together so we understand more. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . BTW: The photo of the audience w/3-D glasses: Imagine! When you went to the movies, men wore ties!

(I wonder if there are links between all this and the ’40s and ’50s NYC street photographers (Ruth Orkin, for example) Robert FRank (who went elsewhere) . . .