On the Trail of Canada’s Black Pioneers

On the Trail of Canada’s Black Pioneers

Growing up in Calgary Cheryl Foggo looked forward to the annual Stampede with excitement – a horse crazy child enamoured of the whole cowboy mystique. But as a young adult she began wondering why her own ancestors, African-American homesteaders on the Canadian Prairies, were absent from Alberta’s foundation myth.

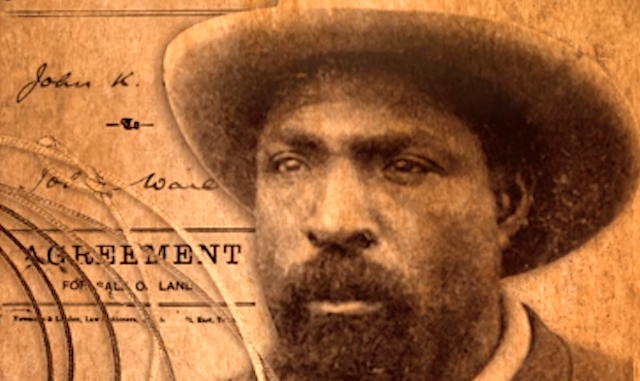

With John Ware Reclaimed, produced out of the North West Studio, she’s shining a light on the underwritten history of Alberta’s Black pioneers and the remarkable life of John Ware.

Born into slavery in the Antebellum South, Ware was already an accomplished cowboy when he arrived in the Canadian west in 1882. “The horse is not running on the prairie which John cannot ride,” reported the MacLeod Gazette in 1885. A legend in his own time, he was the subject of a popular book called John Ware’s Cow Country by prominent Alberta historian and politician Grant MacEwan. Published in 1960 and reprinted many times, the book has locked Ware’s story into an outdated narrative and over time his role in Alberta history has been eclipsed by dominant white settler narratives.

Foggo first began exploring Ware’s legacy within a theatrical context. Her play John Ware Reimagined premiered in Calgary in a production by the Ellipsis Tree Collective and went on to win the 2015 Writers Guild of Alberta’s Gwen Pharis Ringwood Award for Drama.

Tell us about the enduring appeal of John Ware’s story.

Cheryl Foggo: I grew up in Calgary in the 50s and 60s, a time when cowboys were everything, when the Western mythology was Alberta’s most significant identity, and for good or for ill I bought into it one hundred percent. It was only later that I began to feel under-represented, unwelcome in a narrative that contained no reflection of my own people. And then I discovered John Ware, a Black cowboy who’d played a key role in creating the identity of Southern Alberta, with its ranches and cowboys.

It was a life-changing discovery, something I didn’t fully appreciate until I got older and started doing my own research and writing. At a certain point I got interested in my family’s history in this part of the world, and the fact that it wasn’t present in the historical record. And with John Ware, I had another story that had been largely ignored by both the history I’d studied in school and the literary scene I was immersed in.

Why would that be? I started looking at the damage it does when your people are ignored by official history. On one hand we were highly visible — they weren’t many people who looked liked us — yet at the same we were invisible. Our achievements and our struggles were simply not documented, and John Ware’s story also embodied both these aspects. On one hand he was famous. You’ve got John Ware School and John Ware Ridge, various institutions and geographical locations that are named after him, but he’s unknown to most Canadians outside Calgary. Yet he was integral to what Alberta was, to what it has become, and if you accept that Alberta has played an important role in forging Canadian identity, then Ware is a figure of national significance.

On a more personal level – and this is a little embarrassing – I can hardly think about John Ware without getting choked up. I feel a powerful and emotional connection to his journey. It’s almost spiritual. It’s partly to do with my love of Alberta, the place where he lived and where I grew up. And my love of horses. I had lots of exposure to horses when I was a kid. Less so now, but I still love them. So when I think of what I’d like my own legacy to be, it’s to bring forward a more accurate portrayal of John Ware’s life and contribution.

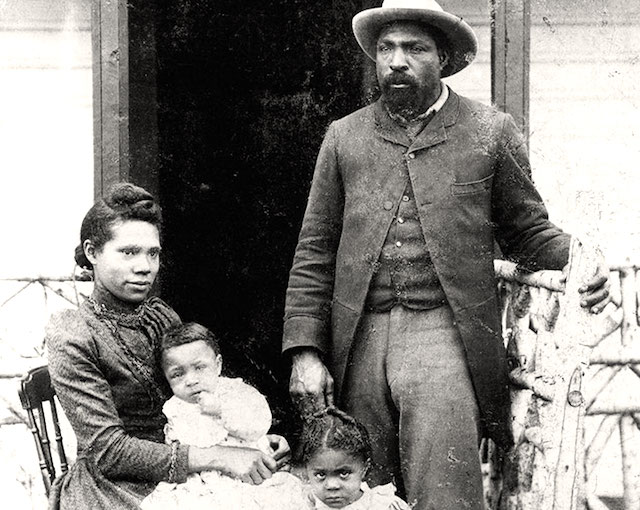

Below: John Ware, his wife Mildred, with son Bob and daughter Nettie.

How does Ware’s story intersect with your own family history?

Cheryl Foggo: My ancestors came to the Canadian Prairies in 1910 from the newly formed state of Oklahoma. They were part of a significant migration — somewhere between 1000 and 2000 Black people, depending on the estimates — who were responding to advertisements that the Canadian government had placed in American newspapers, appealing to Americans to settle in northern Alberta and northern Saskatchewan. People were being offered 160 acres for 10 dollars.

My great grandparents had moved to the Western and Indian Territories in America after the civil war, areas where they weren’t subjected to Jim Crow laws, where they could enjoy a pretty complete slate of rights. They could own property, they could vote, and there were thriving towns that were 100 percent Black. Having fled states where they’d been formerly enslaved, they had every reason to believe they could continue to flourish and thrive in these territories.

But as the state of Oklahoma was being formed, between 1905 and 1907, they lost these rights. Many Black towns were burned down, the number of lynchings skyrocketed, people were stripped of their property and they lost the right to vote. White supremacists mounted aggressive attacks to try to beat our people back into submission. They were generally religious people, so when the Canadian government began placing the aforementioned ads, many saw it as a sign from God.

And so they came north. My great grand parents went to Saskatchewan — settling near Maidstone, North Battleford and Turtelford. One of my great uncles came to Amber Valley, here in Alberta, the most famous of the early Black communities on the Prairies, believed to be the most northerly Black community anywhere in the world. These communities remained closely connected to each other over the years. People travelled back and forth across the Alberta/Saskatchewan border all the time. They knew each other well, married one another and so on.

Below: Children at Toles School in Amber Valley, circa 1945.

When I first started studying John Ware’s life, I still believed the story I’d been told, that he was only Black person in southern Alberta in his time. But as I started doing research into his wife and her family, I discovered that there were already Black people here when he arrived. He had five children who survived into adulthood – including a son Bob and two daughters, Nettie and Mildred – and it turns out that they had connections with people that I considered my own elders. Although I didn’t know it at the time, there’d been times when my life had intersected with theirs.

I’d always believed that my ancestors were part of the first representation of Black people in this part of word, but in fact John Ware was already interacting with an existing Black community, one that had started laying the groundwork for my own people.

What do you hope to achieve with this film?

Cheryl Foggo: Canadians generally know very little about the long rich history of people of African descent in this country. They’re not aware of the contributions made by people of African descent, the way our history has intersected with the settler narrative and the histories of First Nations and Métis communities, going back to the nation’s colonial beginnings. They’re not aware of the struggles and the obstacles we’ve faced in our attempt to find a place where we can express our full humanity, where we can achieve our full potential as individuals and communities. So that’s one thing: we need to build more awareness of how multiracial and multifaceted the people who came here as settlers have always been. Not every Black person you see on the street arrived yesterday. There are tens of thousands of descendants of long-established Black communities across the country. So that’s one part of my agenda: to educate Canadians.

Below: Ware’s sons, Arthur and William, who served in WW1 as part of the all-Black No. 2 Construction Battalion.

But I also think they will find these stories entertaining. That’s the beauty of John Ware’s narrative. It’s so powerful and compelling. He was an amazing person who chose to make Canada his home, to work everyday to have a positive impact on the lives of people around him. Canadians have been deprived of this great story. They’ve been ripped off. So it’s a double gift: I get to educate and entertain.

What problems are there with the existing historical record?

Cheryl Foggo: One of the main sources of information is John Ware’s Cow Country, which was written by Grant MacEwan, an important and revered historian who was once Alberta’s Lieutenant Governor and a former mayor of Calgary. It’s valuable in many ways — there’d be even less conversation about Ware if MacEwan hadn’t written it — but it has its blind spots and problems.

MacEwan dedicates the first three or four chapters to Ware’s enslavement in South Carolina, mentioning a number of people we should be able to find in the historical records. Several professional historians have tried and been unable to confirm these leads. So that’s one problem. Despite my personal admiration for MacEwan, there are aspects of his story that I have not been able to verify.

Another thing is the book’s perspective. It was written in 1960, by someone who had no direct link to the history of the enslavement of African people from the perspective of African people. My own ancestors were enslaved, so I have a personal connection to that history. I’m simply better equipped to tell that particular story. It’s part of my blood and bones. So even though he was trying to tell it from John Ware’s point of view, MacEwan views things through the lens of a problematic power dynamic.

I also want to correct the perception that Ware didn’t mind being called ‘N***** John.’ And I always struggle with how to deal with that word. It’s not a term that I want to elevate. To his credit, MacEwan never claimed that Ware accepted it, but some people come away from his book thinking that Ware would have heard it as a badge of affection — the same way you call someone Red or Shorty. But I dispute that and I take umbrage with it, so that’s another issue with the historical record.

When it comes to race, Canadians sometimes like to congratulate themselves on being better than the USA…

Cheryl Foggo: Yes, and selected aspects of John Ware’s story get singled out and used to bolster that narrative — about how Canadians are not racist, about how we’re better somehow than America. Canada IS different from the United States, and none of my ancestors who came to Alberta were enslaved here, but Canada has its own history of slavery, its own history of racism, and that’s something that people often don’t know.

In 1911 Wilfrid Laurier signed an Order in Council that aimed to limit the immigration of my people, deeming them unsuitable to the climate and conditions of Canada. When I first read that document, it was the faces of my very own grandparents that swam before my eyes. It was very personal for me. So we need to stop congratulating ourselves, to stop comparing ourselves to the US. The real point is to look at how we can become better, in terms of who we are and not in comparison with other places. How can we achieve true equity in this country? Well, one way is to acknowledge the past, a history that we’ve not been truthful about, and to recognize how that history plays out in our present and future lives.

What cinematic devices are you using to bring Ware’s story to the screen?

Cheryl Foggo: I’m approaching the film as one piece within a trilogy. The play was a reimagining, a highly fictionalized theatrical work that contained elements of magical realism. The film is a reclaiming, a very different thing from reimagining. And eventually I plan to write a book, a rewriting of John Ware’s story. So this is the second piece in that trilogy.

In terms of cinematic devices, we’re working with Fred Whitfield, one of the few professional Black cowboys on today’s rodeo circuit. He’s appearing on camera as a kind of imprint of John Ware. He’s about the same size, a skilled horseman and cowboy, and he’s also from the south. So he’s a great stand-in for Ware. It’s beautiful to see Fred riding across the land that’s now called John Ware Ridge, or standing where John Ware once posed for a photograph, proudly showing what he had created, as if to say, ‘This is where I have built my dream.’ It’s been really fun to shoot, and the results are extraordinary, ghostly and powerful.

We’re also having people perform anecdotes from Ware’s life, stories from people who knew him, often in the locations where the events in question actually happened. The writer Lawrence Hill is doing one, and so is my daughter Miranda Martini, who co-composed the music for the play. She’s singing a song, based on an exchange between John and his wife Nettie, that’s called Mildred’s Lullaby. We’re working with people who have a connection either to John Ware or myself, or to the broader story of Black Canada.

Below: Foggo on location with DOP Douglas Munro and archeologist Lindsay Amundsen-Meyer.

Whatever I discover along the way, I want to create a new place for people to start when they study John Ware. That 1960 book was the go-to document for a long time, and I would like this film to be the new go-to document.

Tell us about your team.

Cheryl Foggo: My DOP Douglas Munro and my editor Margot McMaster, who happen to be a couple, are both great members of the team. They’ve been sitting in on meetings from the beginning, and worked on the pre-shoot we did with Fred Whitfield two years ago. They can actually see John Ware Ridge from their office, and Doug has a great eye for that landscape, for how to shoot it in the best possible light, both literally and figuratively. Frank Russo has been recording sound – and he’s great, so meticulous.

Early on Bonnie [Thompson, a former NFB producer on the project] asked me I’d like to mentor someone, and we’ve brought Ami Kenzo on as production assistant. She’s a young Black woman who’s been working in different areas of the film industry for a few years now, and she’s a real asset to the project. Plus she’s part of my target audience. I see my audience as containing many diverse elements, but I’m always trying to create work that would have meant something to me as a young woman. And Ami reminds me of my younger self: we connect on an emotional level.

What role does music have in this project?

Cheryl Foggo: I see music as another character in this story, and I’ve been working with a number of local musicians —my daughter Miranda, the poet and musician Kris Demeanor, and a few others.

Music is another way to make connections between my life and John’s, so I’m using lots of music and song that I heard growing up, in church and elsewhere, old and powerful music that was also present in Ware’s life.

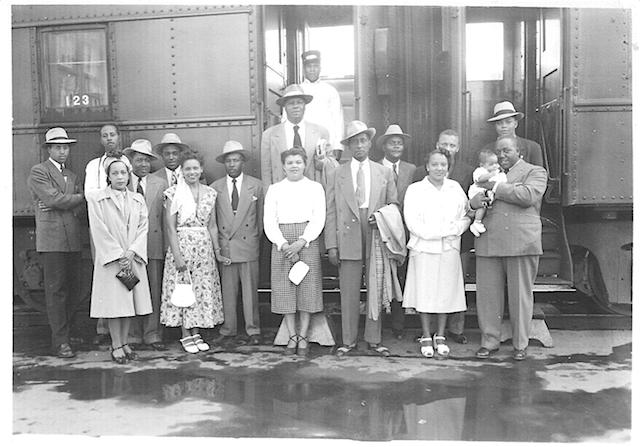

Below: Albertan railway porters and their wives at the Calgary train station, courtesy of Joan Armstead.

What part has the NFB played in your film career?

Cheryl Foggo: My first professional gig in the film industry was at the NFB. I co-wrote the script for a short educational film called Carol’s Mirror, directed by Selwyn Jacob. And the first project that I wrote and directed myself was another NFB film, The Journey of Lesra Martin, which Selwyn produced.

The NFB not only provides an incredibly good support system, but it’s also symbolic of the best of who we are as Canadians. Although not always successful, it attempts to be representative of who we are as a nation. When I was little, there were still people alive in my family who’d come to Canada as part of that original 1910 migration, and they were some of the fiercest Canadian patriots that I’ve ever encountered. I’ve since come to realize that their brand of patriotism was based partly on denial and suppression of fact, in that they didn’t want to talk about the difficulties they’d encountered. They didn’t want to talk about that order in council that was signed by Wilfrid Laurier.

But for whatever it’s worth, I was raised to believe in the Canada that we think we are, and some part of me still believes in the Canada that we could still be someday. I’m striving to make my contribution to that conversation, a conversation that’s hard to hear for people who’ve not been exposed to a truthful representation of what the Canadian experience has actually been like for lots of people. But the NFB is a place where my voice can be heard, and that’s a unique opportunity that I recognize as a privilege.

John Ware Reclaimed, a production of the NFB North West Studio, is directed by Cheryl Foggo, produced by Bonnie Thompson & David Christensen and executive produced by David Christensen. Photography courtesy of Cheryl Foggo and the NFB unless otherwise indicated.

Banner image: Cheryl Foggo and Fred Whitfield, photo by Shaun Robinson.

Updated August 20, 2020.

Do you know of any in the story that settled down with First Nations’ as wives or husbands? Blackfoot and Stoney have family histories that suggest this may have happened more than is reported. A fine project.

Hi Thomas,

Yes, there were many ties of marriage and friendship between people of African descent and the First Nations people in the region, from the 1800s through the present. One of the more famous examples is Henry Mills, who preceded John Ware in what is now known as southern Alberta. If I recall correctly he worked for the HBC. His son Dave Mills lived among the Bloods and married Holy Rabbit Woman. I hope to explore and write about more of these relationships in the future. Thanks for the question!