Freedom Road: Angelina McLeod Makes her Way Home

Freedom Road: Angelina McLeod Makes her Way Home

Over four hot memorable days this past June the people of the Shoal Lake 40 First Nation celebrated a momentous collective achievement.

A road-building crew, consisting largely of local band members, had recently completed the final link of Freedom Road, a hard-fought-for gravel artery that links the community to the Trans-Canada Highway.

Years in the planning, conceived and driven by the community itself, the twenty-four-kilometre road ends a century of punishing colonially imposed isolation and opens up untold new possibilities for Shoal Lake 40 and its people.

Freedom Road: Context, Angelina McLeod & Paula Kelly, provided by the National Film Board of Canada

“This project brought me home”

Filmmaker Angelina McLeod, daughter former chief Alfred Redsky, left Shoal Lake 40 over twenty years ago to finish high school, attend university and pursue a career – but Freedom Road would bring her home.

For over two years she documented the trail-blazing process from within, inviting participation from a multitude of community members — from the elders who spearheaded the initiative over 15 years ago to the young men who poured the last load of gravel.

The result is a vibrant short film series whose structure mirrors the community’s own governance circles, with four shorts dedicated respectively to Ininiwag (men), Ikwewag (women), Oshkaadiziig (youth) and Gitchi-aya’ aag (elders), followed by a film that provides context for their historic accomplishment.

“This project brought me home,” says McLeod, recalling the enthusiastic response that Freedom Road received when she screened it to fellow band members in the local school gym as part of the June festivities. “We’ve all endured hardships in Shoal Lake 40 and this project has been a good way of sharing our stories, a way to heal and move forward.”

Gimme Some Truth: new willingness to confront brutal legacies

Freedom Road gets its world premiere on November 5 as the opening night program of Gimme Some Truth, the Winnipeg Film Group’s annual showcase of contemporary documentary cinema. The launch event has been planned in partnership with the NFB, The Decolonizing Lens, The Winnipeg Art Gallery and Friends of Shoal Lake 40, and McLeod will participate in a post-screening panel alongside fellow band members Daryl Redsky and Roxanne Greene and Winnipeg-based historian Adele Perry.

“It’s great to have support from so many different groups in Winnipeg,” says Alicia Smith, who produced the series at the North West Studio. “Shoal Lake 40 has worked hard to lay down the groundwork, building alliances in Winnipeg and beyond. I think there’s a growing collective desire in the city to engage with the issues facing Shoal Lake 40, and to reconsider the relationship between the Shoal Lake 40 and Winnipeg.”

Shoal Lake 40 Chief Erwin Redsky, speaking recently to journalist Kyle Edwards of Macleans Magazine, puts its this way: “Shoal Lake 40 is an iconic story of a broken relationship. But it can also be the model of the new relationship that needs to take place with Indigenous peoples of Canada.”

Cruel colonial ironies

The vast western regions of the Lake of the Woods watershed have been home to the Annishinaabeg and Ojibway for millennia, but in the late 19th century, as part of the terms of Treaty Three, the community of Shoal Lake 40 was established in its current location. Meanwhile Winnipeg was in rapid expansion 100 kilometres to the west — and in the early 20th century city officials set their sights on Shoal Lake as a possible municipal water supply.

In 1913 work began on the Winnipeg Aqueduct, designed to transport water from Shoal Lake to the growing Prairie metropolis, and by the time it was finished, the Shoal Lake 40 First Nation had lost over 3,000 acres of treaty land and its people had been left stranded on a man-made island where, in a particularly cruel colonial irony, they have been forced to live under a boil-water advisory since 1997.

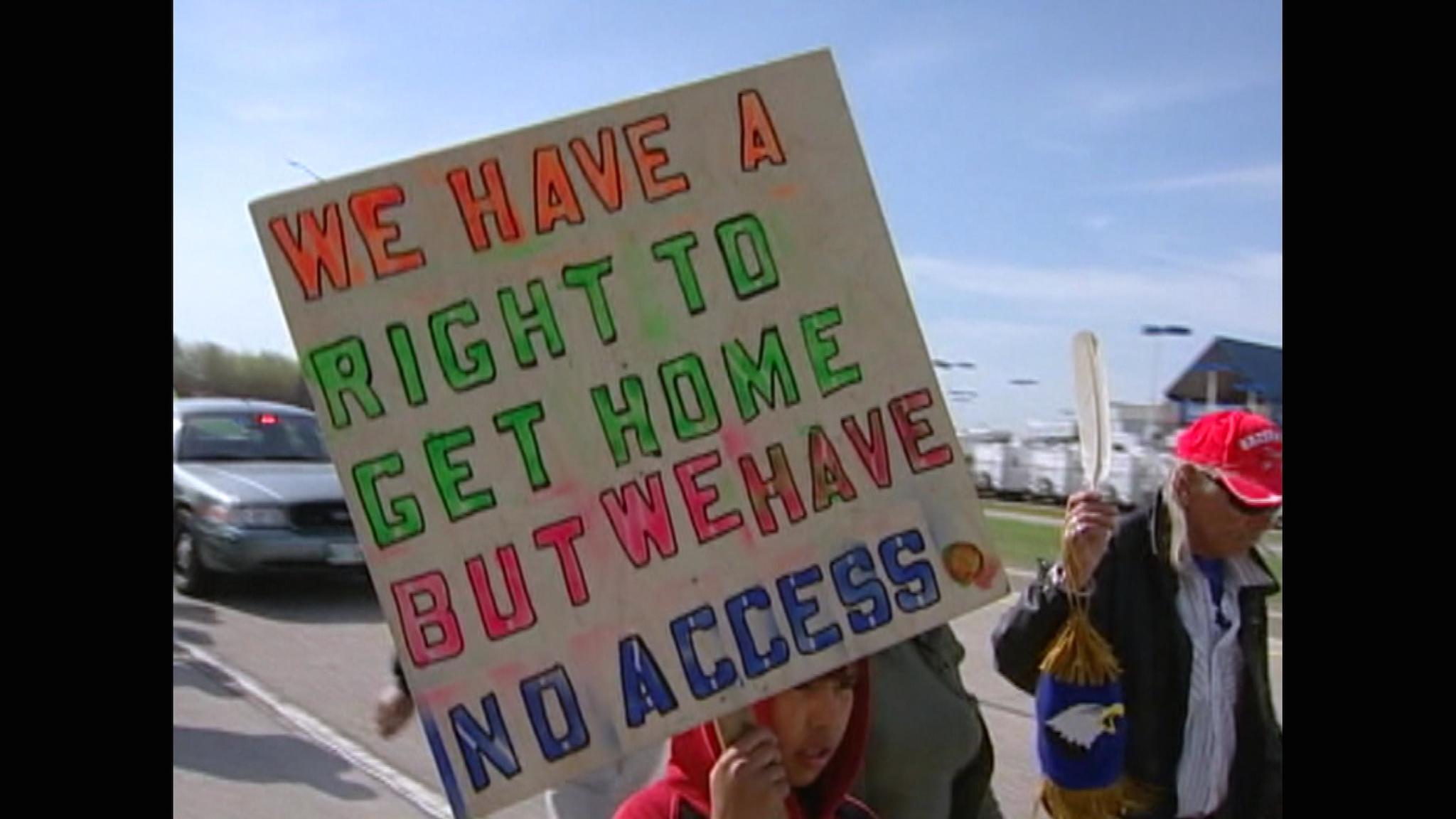

Up until this year their only link to the mainland was an unpredictable summer ferry service and a winter ice road. Many speak of transporting sick family members over dangerous ice during the fall freeze and spring thaw, and many families have had someone drown while attempting the crossing.

“Crossing the ice during ice break-up and freeze-up was always scary,” says McLeod. “I fell through the ice once but managed to get myself up and out safely. But one of the hardest things was having to leave home for high school. I had to leave to attend Grade 9 and go to a boarding home in Kenora, Ontario. I had to get used to living in a colonialized world, full of racism, where many people had no understanding of what it’s like to live as an Indigenous person in this country.”

In an echo of a tragedy that touches so many Indigenous communities across Canada, McLeod’s sister disappeared while attending high school in Kenora. “She went missing and was later found deceased. I still don’t know what happened to her. I probably never will.”

“You don’t have to be a chief to lead”

As the community turns a page on this history, band members like Daryl Redsky have been playing a key role. One of many featured subjects in Freedom Road, he was also employed by the production as a community advisor, providing cultural awareness training to a mixed Indigenous/non-Indigenous crew.

Like many Indigenous people of his generation, Redsky identifies as survivor of complex intergenerational trauma and at a pivotal moment in the introductory film, he speaks of valuable advice he once received from Angelina’s father when he asked the elder to preside over a traditional feast. “He said to me, ‘How are you ever gonna learn what to do if you keep running to us? You know what to do.’ So that was a teaching. He was telling me in a stern way to pick it up. Pick it up and do it.”

Since then others have risen to the occasion, assuming leadership roles within the community as it looks to new horizons. As Lorne Redsky declares in the Ininiwag film: “You don’t have to be a chief or a councilor, or a judge or lawyer or cop, to want to lead your people.”

Drawing inspiration from Challenge for Change

Freedom Road is one of several projects currently in release or production at the NFB that draw inspiration from Challenge for Change, a participatory media program that was active at the NFB between 1967 and 1980, giving birth to the famous Fogo process, a methodology developed in rural Newfoundland whereby film became a tool for community organizing and social change. With The Lake Winnipeg Project, currently in production, Kevin Settee has adapted this approach to engage with Indigenous communities in the north basin of Lake Winnipeg, investigating issues relating to water, land and hunting and fishing rights. Scott Parker employs a similar methodology in the recently released Grasslands Project, which documents contemporary life across the Southern prairies of Alberta & Saskatchewan.

McLeod’s crew on Freedom Road included the brother team of Tyler Funk, chief cinematographer, and Jason Funk who was the drone operator. The sound recordist was Charlene Moore, a driving force behind the recent Indigenous Film Summit whose own short film When the Children Left screened at the recent edition of imagineNATIVE. Freedom Road was edited by Erika MacPherson, produced by Alicia Smith and executive produced by David Christensen for the North West Studio. Watch for news of its online launch.