A Universe of Imagination: The 60-Year Odyssey for a NFB classic

A Universe of Imagination: The 60-Year Odyssey for a NFB classic

“We established the premise that imagination can travel faster than the speed of light. Imagination being an unmeasurable entity, our new premise didn’t seem to upset any other physical laws.” – Sidney Goldsmith, Universe Production Designer (with Colin Low)

Sixty years after its premiere at the Cannes Film Festival (where it won the first of dozens of international awards in the years to follow, and an Oscar nomination) the NFB short documentary Universe, directed by Roman Kroitor and Colin Low, remains a revered classic. Its influence on filmmaking, its poetic approach to science, and its ground-breaking special effects all affirm the NFB’s commitment to collaboration and experimentation. In some ways it is a quintessential NFB film, in that it drew on the best of both its animation and its documentary craft traditions.

Seen online in at least 146 countries, sold to countless broadcasters around the world, and available in many languages (including French, Danish, Portuguese, Norwegian, Malay, Swedish, German, Serbo-Croatian, Mandarin, Finnish, Spanish, Arabic, Dutch, Hindi, Italian, Japanese, Korean, Polish, Russian, Tamil, Thai, and Cantonese), its reach has spanned the globe and the decades. It might be the most-viewed NFB film in history.

A journey from the particulars of daily life—a giant’s eye view of traffic and busy pedestrians, reflected sunlight dazzling from seven skyscraper windows—to the farthest reaches of the universe, it takes us on a metaphysical voyage. Indeed, the original proposal for the film (then called, in what now seems like a bureaucratic stroke of understatement, Astronomy) foresees a cinematic adventure that is really an exploration of the human soul.

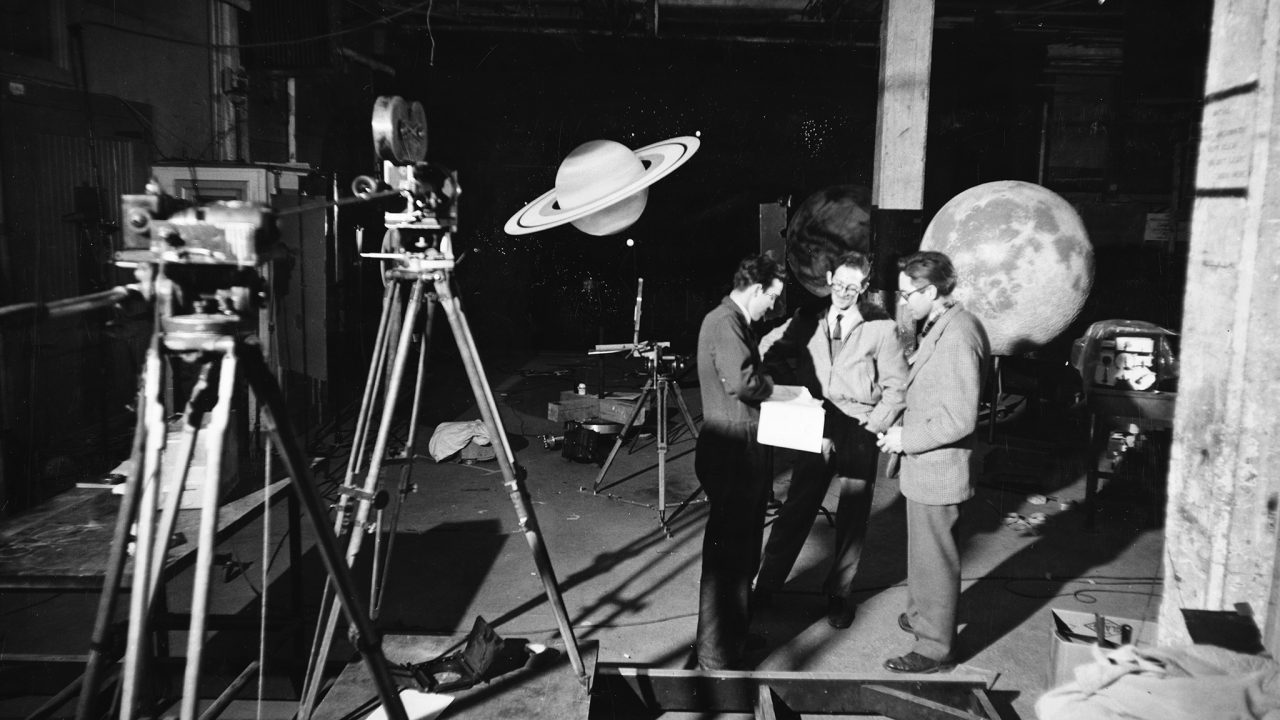

And it delivers on the astronomical (the budget, close to $1 million in today’s dollars, and its time in production, about seven years, were both seen as astronomical, so to speak…) and the philosophical. Even to our jaded eyes, accustomed as they are to seamless digital realism on screen, the film’s astonishing animation still impresses, aided by, among other things, its artful use of ping-pong balls and sanded globes. Its music score carries the viewer through stages of spectacle and understanding, and occasionally terrifies. The writing serves its purpose for a “classroom film” but elevates it far beyond the purely didactic. And the film’s voice, that of the late Douglas Rain, re-invents narration for the time, its patience, cadence, and intelligence all emblematic of a Stratford Festival star whose performance in this film led to Stanley Kubrick casting him as the inimitable HAL 9000 computer in 2001: A Space Odyssey.

Parts of the film are profound in their scale and implication, generating awe with eerie wisps of gigantic comets, lines like “if we could move as a god,” and disturbingly graphic facts about Jupiter’s gravity (“a human being would be crushed beyond recognition”). The film connects our earthbound obliviousness to the astronomic reality that “the ground beneath our feet is the surface of a planet whirling at thousands of miles an hour around a distant sun.”

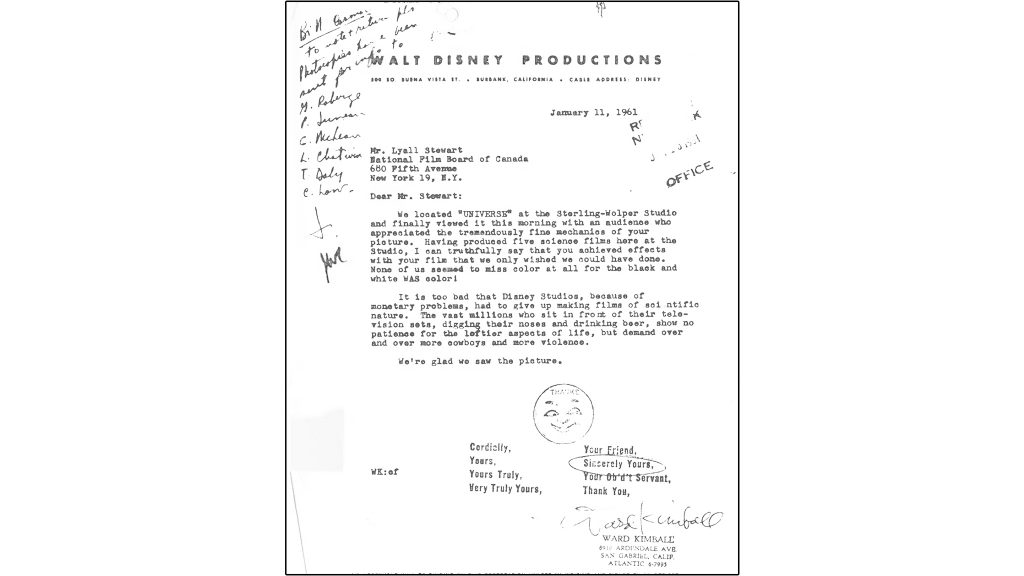

Aeon Magazine declared that “Universe altered the course of cinema’s evolution,” such was its impact on Kubrick, who, after seeing the film almost 100 times, and wearing out his 16mm print in the process, tried to hire the entire NFB animation and effects team (one member of the special effects team, Wally Gentleman, did go, but ended up hating 2001!), even musing to Colin Low about the possibility of shooting 2001 at the NFB’s sound stage in suburban Montreal.

At one point, Kubrick considered calling his film Universe. Kubrick’s collaborator, science-fiction author Arthur C. Clarke, wrote that “there was a possible sequence planned for the film, to be entitled Universe to describe ‘the scale of the cosmos.’” One can’t watch 2001 without seeing the visual echoes from Universe.

Low noted, in an interview with Marc Glassman, that the U.S.-Soviet space race helped get the film over the finish line: “The Russian Sputnik went up in 1957 and then there was pressure to finish the film. NFB management also stopped complaining about the cost overruns.” NASA was so taken with the film that they ordered 300 prints. Years later, in 1976, William Shatner narrated a plodding NASA-funded knockoff of Universe titled, imaginatively, Universe.

As is sometimes the case with what come to be appreciated as legendary artistic collaborations, Rain’s with the NFB wasn’t the smoothest. When I spoke to Rain in 2014, he said he felt he had done great work on Universe but hadn’t particularly enjoyed the experience: “I had six people at NFB with notes coming at me, none of which made sense. I told them: ‘You are not conveying it to me, I will take direction from one person.’”

Tail credits on NFB films weren’t very exhaustive in those days, so Rain’s name doesn’t even appear on-screen; only NFB wordsmith Stanley Jackson is credited under “Commentary,” which Rain said delayed Kubrick in finding him. All ended well enough, as just a few weeks before the film’s Cannes premiere, Roman Kroitor invited the actor to view a test print, adding “it seems to have come off quite well. We like your voice on it.”

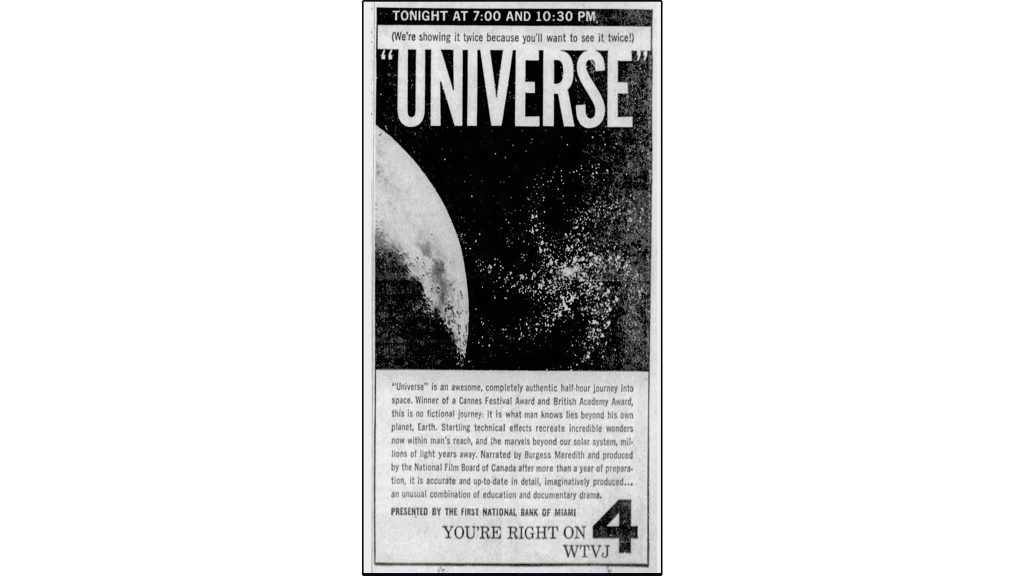

It certainly came off quite well in the U.S. Universe was a hit on American television in the early 1960s, sometimes shown twice on the same evening. One fan of the film remembers seeing it on local TV station WPIX in New York in November 1963 as the first program broadcast immediately following President Kennedy’s funeral.

Universe remains not only a reliably popular NFB film online, but a source of imagery for new productions. Even its documentary “outs” (vividly shot imagery of the streets of 1950s Montreal and Toronto not used in the final film) wonderfully capture the texture of Canadian urban life of the time. And, according to Lea Nakonechny, NFB Archives Sales Manager, it is one of the few animated films from which filmmakers seek excerpts. Watch for some galactic beauty from Universe in a scene from UK filmmaker Steve McQueen’s new BBC/Amazon Prime drama Small Axe this month.

In a year when we have all questioned so much, and the appetite for understanding ‘the big picture’ has only grown, maybe Universe is the film we didn’t realize we needed. It ends with this question, spoken by Rain as we fly over an endless icy plume of a galaxy: “In all of time, on all the planets of all the galaxies in space, what civilizations have risen, looked into the night, seen what we see, asked the questions that we ask?” But the film really ends with a gorgeous, sunny morning outside the David Dunlap Observatory, birds chirping, the Earth ours to embrace.

Watch Universe:

Universe, Roman Kroitor & Colin Low, provided by the National Film Board of Canada