Back to the Future, or A Short History of the Filmstrip | Curator’s perspective

Back to the Future, or A Short History of the Filmstrip | Curator’s perspective

No one knows what the future holds, or so the saying goes. And yet with this endless pandemic and the rapid development of new technology, it seems highly likely that the future of the NFB’s teaching resources is, more than ever, online, whether it be streaming films, interactive online experiences, apps, VR projects or social media content. But what were such tools like in the early days of the NFB? What was the future of education back in the 1940s?

As we find ourselves in back-to-school mode, I thought it would be interesting and somewhat amusing to try and answer this question. So let’s journey back to the future that once was.

Filmwhat?

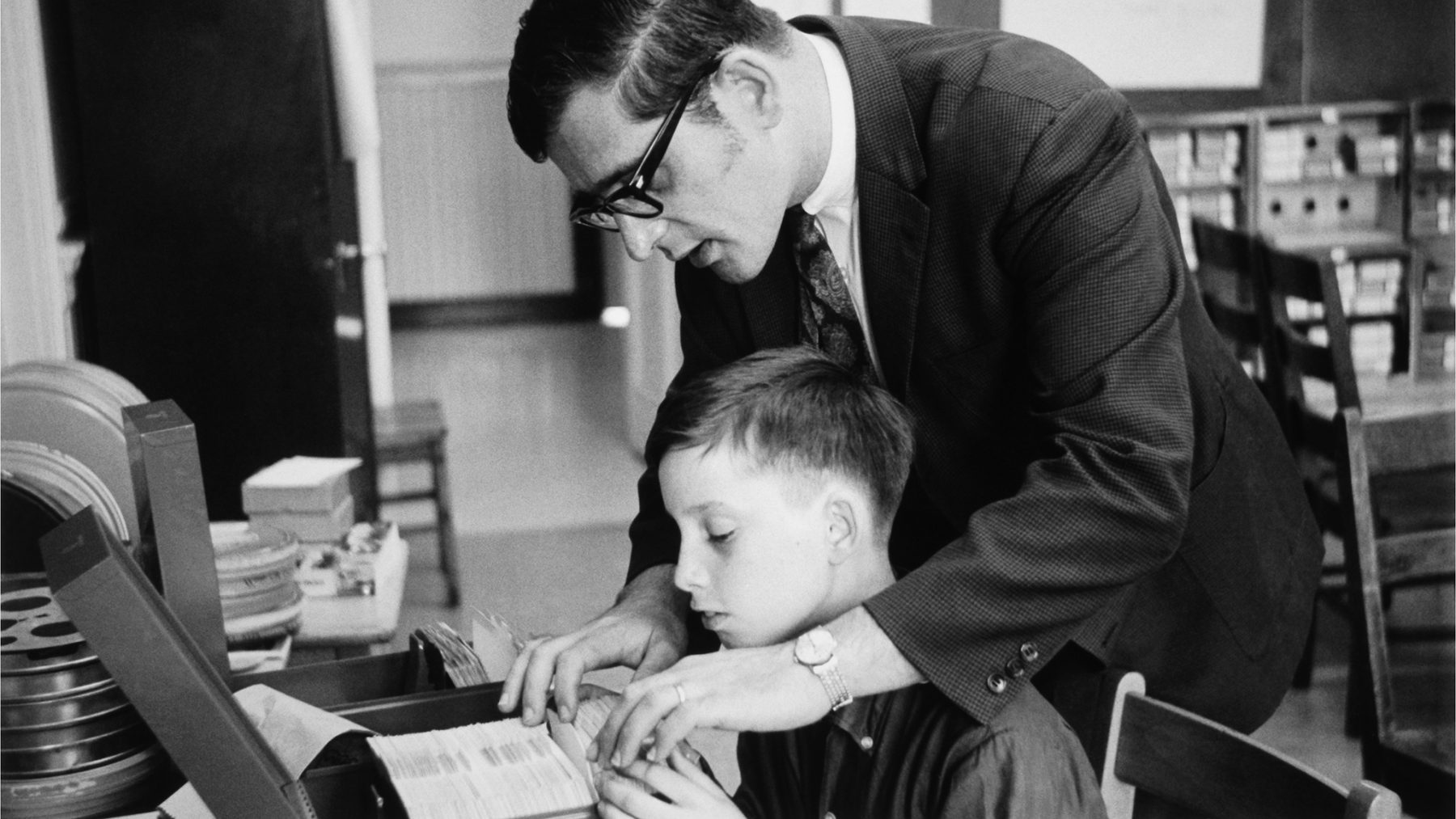

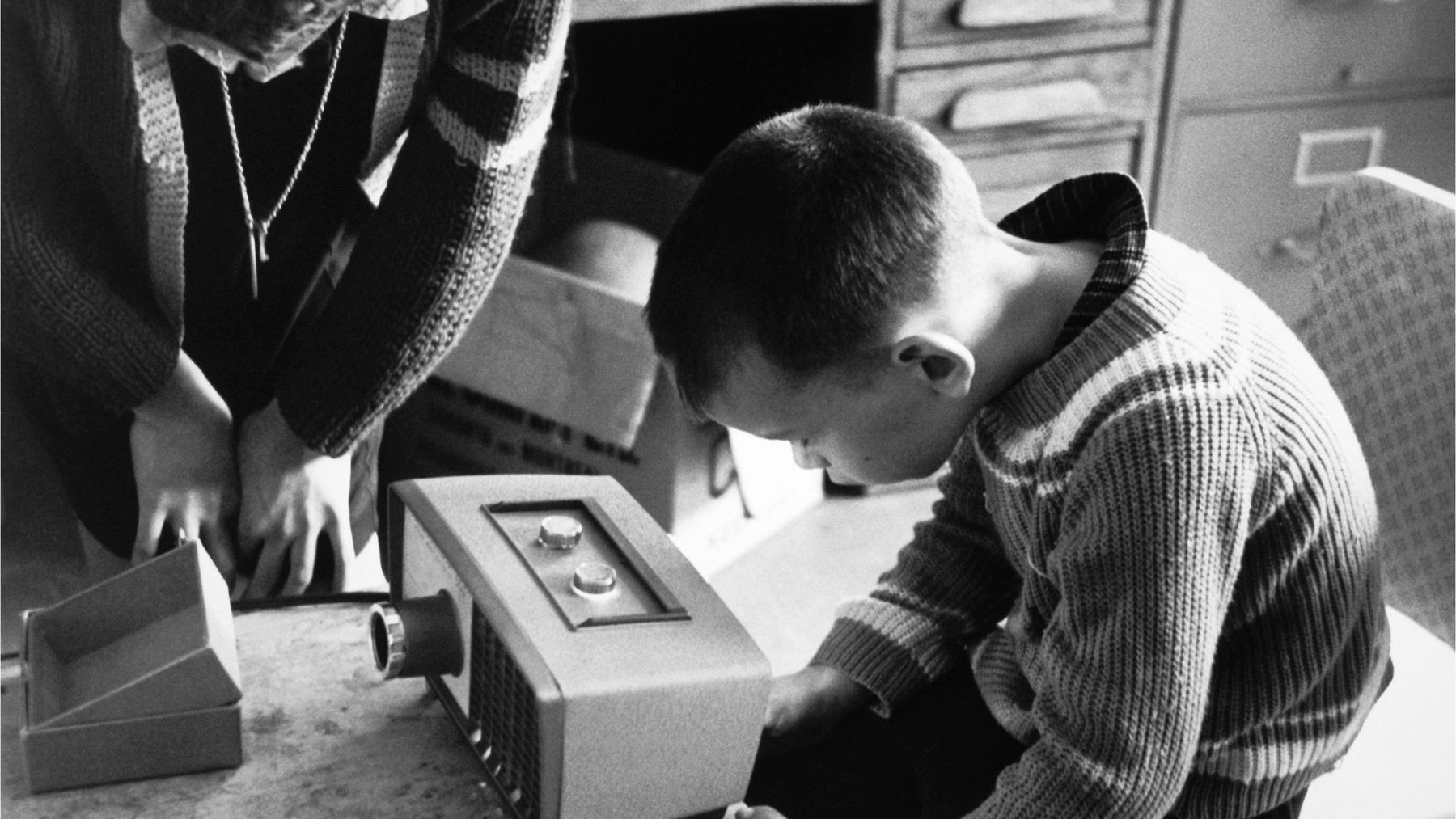

The NFB began producing educational material after the end of World War II. But what did this material actually consist of? Answer: the filmstrip. The film what, now? The filmstrip was essentially a series of images on a roll of 35-mm film that was inserted into a projector. This allowed teachers to project one image at a time onto a screen. Later, the images would be accompanied by music or narration on a vinyl record, or by a written commentary that the teacher could read aloud. The popularity of filmstrips grew throughout the 1940s, and they quickly came to be viewed as the educational resource of the future.

Military training tool

The NFB produced its first filmstrips in 1943. Initially, they were used as educational and training tools for the military, but their amazing potential as a learning resource for the classroom was quickly apparent. In 1946, the NFB’s graphics department set up a black-and-white filmstrip production program, making 20 filmstrips its first year. It was an instant hit. By the end of the 1947–1948 fiscal year, 1,100 copies of these 20 filmstrips had been sold to schools and libraries.

A burgeoning studio

By the 1950s the program had grown into a full-on filmstrip production studio. Every year, the studio produced 60 to 90 filmstrips in colour and black and white. In 1957, Canadian and international sales of filmstrips totalled more than $16,000 (back then, a black-and-white filmstrip sold for $1.50, a colour filmstrip would cost you $3.50, and a filmstrip with an accompanying soundtrack would set you back $5.50). Filmstrip subjects varied from history and geography to art and literature to farming, the natural sciences and health.

Fairy tale

In 1958, the studio produced Cendrillon (Cinderella), a colour filmstrip for teaching French, made from drawings by students at a Montreal elementary school. The music was written by an NFB composer and performed by NFB musicians. Cendrillon would later be adapted into an animated short film in 16-mm format, with the title The Story of Cinderella (1958) in English and Un conte de fées: Cendrillon (1961) in French.

A popular song

Filmstrips became increasingly sophisticated. Most were in colour and included diagrams, maps, drawings and even paintings produced by artists working at the studio. Cadet Rousselle (1959) is an excellent example. This gem was made entirely from illustrations by the painter Jean Dallaire. Later, a recording of Félix Leclerc performing the well-known French folksong was added. Thirty years later, for the NFB’s 50th anniversary, filmmaker Daniel Frenette made it into an animated film entitled Félix Leclerc chante Cadet Rousselle (1989).

An indispensable tool

In the 1960s, filmstrips could be found in schools across the country and were at the peak of their popularity. They were translated into other languages, adapted and sold internationally, primarily in the US, England and Sweden. They were also used as supplementary material for films on the same subject. Examples include The Long March West (1961) on the history of the RCMP, which complemented Colin Low’s film The Days of Whiskey Gap (1961), or Lord Durham (1961), used in conjunction with John Howe’s film of the same name in The History Makers series. Filmstrips had become indispensable tools for teachers, and they were produced with school curricula and teaching methods in mind.

The Days of Whiskey Gap, Colin Low, provided by the National Film Board of Canada

Multimedia

In the late 1960s and 1970s, the NFB developed new teaching tools, such as 8-mm film spools, slide and picture games, and what were, at the time, called multimedia sets. Filmstrips, while still distributed separately and highly popular, were a part of these multimedia sets, along with 8-mm films, slides and photographs. The great Abenaki filmmaker Alanis Obomsawin made one of these sets—the Manawan (1972) series, a unique look at the Atikamekw community of Manawan. The seven films in this series are still available on our Indigenous Cinema page.

History of Manawan – Part One, Alanis Obomsawin, provided by the National Film Board of Canada

Studio G

In the early 1980s, a new NFB studio was created—Studio G—which would henceforth oversee the production of filmstrips and multimedia sets. While filmstrip demand remained steady, and sales continued to be strong until the mid-1980s, production declined considerably. Studio G began to focus on video production, and the NFB began to encourage the distribution of its films on videotape to schools and libraries.

By 1989, the studio had ceased production of filmstrips and was concentrating on educational series on video. The release of the Pour tout dire series in 1988 and Perspectives in Science a year later spelled the end for the filmstrip, lowering the curtain on its 40-year history.