Mini-Lesson for A Passage Beyond Fortune

Mini-Lesson for A Passage Beyond Fortune

Mini-Lesson for A Passage Beyond Fortune – Myth-Busters: Reclaiming a Voice

School Subjects:

- Media Education: Advertising/Marketing

- English Language Arts: Journalism, Voice

- Diversity: Diversity in Communities, Identity

- Civics and Citizenship, Social Studies: Communities in Canada

Recommended Ages: 15–17

A Passage Beyond Fortune, Weiye Su, provided by the National Film Board of Canada

Keywords/Topics: Chinese-Canadian Communities, Immigration, Systemic Discrimination

Educational Synopsis: This mini-lesson will explore Canada’s anti-Chinese policies through a historical lens, while unpacking the marketing of the “tunnels of Moose Jaw” tourism and its harmful contributions to anti-Chinese systemic discrimination. The lesson will also help students analyze the role of voice in storytelling, through media literacy and a focus on reclaiming voice and narrative.

Overarching Question: Why is it essential to explore and share the stories of Chinese-Canadian immigrants as a means of validating their experiences, rather than relying on tourism or urban myths?

Activity 1: Cause and Consequence

Have students complete this activity before watching the film to provide context.

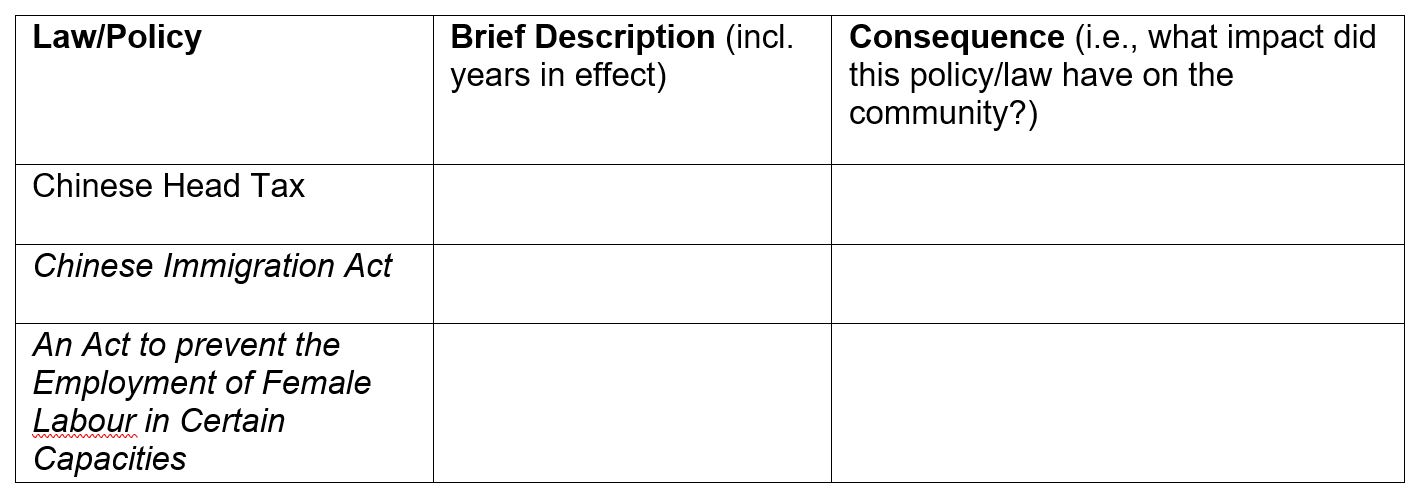

Divide the class into three groups. Each group will research their assigned law or policy from Canadian history and complete the chart below. The film briefly refers to the policies below, all of which impacted Chinese immigration.

- Chinese Head Tax

- Chinese Immigration Act

- An Act to prevent the Employment of Female Labour in Certain Capacities, commonly referred to as the “White Woman’s Labour Laws.”

Next, ask each group to present their findings to the class to provide context for the issues the film raises.

Watch clip: 2:55 – 6:54

Class discussion: How do laws or policies enforce stereotypes and prejudice?

Summary:

The goal of this activity is to introduce students to the definitions, laws and policies that shaped Chinese immigration to Canada from the 1880s to the late 1960s. This activity is focussed on the historical thinking concept of cause and consequence.

Activity 2: “They worked for themselves”: Marketing Myths and Systemic Discrimination

Watch clip: 00:18–2:50

Film quote to support the overarching question:

“In the 1980s, a series of underground tunnels were discovered. This inspired an urban myth that Chinese people lived underground, forced to work for white business owners. In 2000, a tour company started selling this story. It became an attraction for people to learn about Saskatchewan’s history. After the tour, I felt ashamed and disrespected. I wondered what the Chinese community had to say… the truth is many of these early immigrants were successful in Moose Jaw and owned their own business. They worked for themselves. What I saw in the tunnels was far away from their stories.” – Weiye Su, narrator and director

Pre-discussion: As a class, develop a definition for “systemic discrimination.”

- Think-Pair-Share

Introduce the discussion and explore the role of media marketing and advertising and its connection to perpetuating stereotypes:

- Some of the discriminatory policies against Chinese people (Chinese Head Tax, Chinese Immigration Act, the “White Woman’s Labour Laws”) led to systemic discrimination and the breakdown of Chinese immigrant families. In the film, director Weiye Su states that the tunnels are marketed as “historical” despite no historical evidence to support this claim. How does the marketing of the tunnels as “Canadian history” contribute to systemic discrimination and the misrepresentation of the Chinese-Canadian community today?

- Alternate question: How do these hyperbolized urban myths contribute to systemic racism, perpetuate stereotypes, and ignore the true experiences of early Chinese immigration in Moose Jaw, Saskatchewan?

- Mind Map: Further Connections to Media Literacy

Ask students to consider the implications of misleading tourism, beyond the tunnels of Moose Jaw. In groups or individually, create a mind map responding to a broader impact question: Why does a tourist attraction have a more harmful impact than a rumour or myth?

(Media-literacy concepts to support answers include credibility, fact-checking, construction of a false narrative, audience.)

Summary:

The goal of this activity is to encourage students to question the harmful impact of the media and the marketing of an urban myth about the tunnels of Moose Jaw, and to explore how the myth detracts from the individual immigration stories and contributes to systemic discrimination. This activity is focussed on connections to media literacy and could also be related to the historical thinking concept of continuity and change.

Activity 3: Reclaiming a Voice

We recommend watching the full 15-minute film before beginning this activity. For clips featuring quotes by the narrator, watch:

Clip no. 1: 00:18–2:50

Weiye Su (narrator): “Someone once told me in Saskatchewan every town has a Chinese restaurant and story. Moose Jaw has more than one. Chinese people have been part of this community for generations. Their history runs deep here. In the 1980s, a series of underground tunnels were discovered. This inspired an urban myth that Chinese people lived underground, forced to work for white business owners. In 2000, a tour company started selling this story. It became an attraction for people to learn about Saskatchewan’s history. After the tour, I felt ashamed and disrespected. I wondered what the Chinese community had to say.”

Gail Chow: “When the tunnel started, they never talked to the Chinese community.”

Su: “The truth is many of these early immigrants were successful in Moose Jaw and owned their own business. They worked for themselves. What I saw in the tunnels was far away from their stories.”

Clip no. 2: 14:35 – 15:20

“Someone once told me in Saskatchewan, every town has a Chinese restaurant and story. The first story I heard in Moose Jaw was about the tunnels. It was told that it was true, but it wasn’t. As immigrants it is important our experiences are respected, so we don’t repeat the past. Telling our stories allows us to reclaim history and make space for generations to come.” – Weiye Su, narrator and director

Weiye Su begins and concludes the documentary with the statement, “Someone once told me in Saskatchewan every town has a Chinese restaurant and story,” before explaining the urban myth of the tunnels, followed by the Chow family’s immigration story. He ends the documentary by saying, “The first story I heard in Moose Jaw was about the tunnels. It was told that it was true, but it wasn’t.”

Class Discussion: What is the purpose of exploring the Chow family’s immigration story as a response to the tunnel myth?

Write a 1–2 paragraph response to one of the following prompts:

- Myth: How does the narrator’s use of the tunnel myth effectively frame the film’s focus on the Chow family’s story?

- Voice: Consider the role of voice in the film. Why is it more effective to directly hear the Chow family talk about their experiences rather than reading about them or hearing a paraphrased version? Consider the point of view and tone in particular.

- Medium: How does the medium (film) convey the purpose of reclaiming the narrative more effectively than a written account?

Summary:

The goal of this activity is to help students analyze how stories are told and to explore how the medium impacts the storytelling. This activity is focused on media literacy, literary techniques and voice in narratives.

Take Action: Myth Busters: A 60-Second Documentary Series

Explore short films and stories of regional and personal stories of immigration to support the depth of student thinking before beginning this project.

Students will find and interview a person in their community whose immigration story inspires and interests the student.

Students will create a 60-second documentary exploring the prompt: “What is an assumption, myth, or stereotype that someone thinks about you that you would like to address?”

Students are encouraged to use the NFB Media School lessons to support their documentaries (especially Module 1: What Is a Digital Story?, Module 5: Original Angle and Narrative Structure, and Module 9: The Art of Editing).

Postscript

The Chinese dialect spoken in this film is Cantonese.

The New Year celebration depicted in the film is Chinese New Year, or more broadly, Lunar New Year. Some Chinese traditions shown in the film include the lion dance and the giving of lai see (red envelopes) filled with money for good luck and wishes of prosperity.

This mini-lesson was written in collaboration with project consultant Felicia Yong.

Felicia Yong is a secondary English and Visual Arts teacher in London, Ontario. She believes incorporating voice, choice and representation empowers students to become empathetic creators. Felicia is interested in storytelling through data visualization and returning to imaginative and playful art in the secondary classroom. Collaborating with others continues to inspire her to reimagine learning possibilities.

Contextual Information

Historical Background

For over a hundred years, from the late 19th through the late 20th century, Chinese migrants to North America were the targets of racial discrimination and immigration exclusion and control. As targets of government surveillance, Chinese migrants were usually detained before being allowed to cross borders.

They were forced to give details about their origins and destinations, and were physically described and measured. Chinese people were given identification papers and tracked in government data sets long before other migrants came under the same regime of documentation. In comparison, European migrants passed through ports into Canada and the United States with relative ease, leaving much less paperwork.

World History Context

Worldwide, roughly 100 million people outside of China are descended from ethnic Chinese migrants who left China over the last five centuries, and the vast majority of them came from just two southern coastal provinces—Guangdong and Fujian.

Within those two provinces, villages in a handful of counties were the main sending regions for century after century of continual out-migrations that created elaborate communication and transportation networks connecting these regions to an array of destinations around the globe. Beginning with short-distance networks and then expanding to Southeast Asia and around the Pacific, by the late 19th and early 20th century, migrants were establishing and following circuits that took them as far as Africa and South America.

Currently, Chinese migrants now come from every part of mainland China as well as from all the parts of the globe where earlier Chinese migrants had settled. Chinese immigrants to Canada since the year 2000 come from almost every province and region of China.

Gold Mountain and the History of Chinese in Canada

Eight particular counties in Guangdong province dominated 19th- and 20th-century Chinese migrations to Canada, the United States, Australia and New Zealand. Beginning with the “gold rushes” to California and up and down the North American coast in 1849, and continuing around the other side of the Pacific to the Australian colonies of the British, migrants fuelled their journeys with dreams of gold.

Chinese migrants made up a large proportion of the “gold rush” to British Columbia after the news of gold being found in the Fraser River in 1858. In the Chinese dialects that the migrants spoke (Cantonese, as opposed to Mandarin, the current national language of mainland China), they were going to “Gum San”—literally, Gold Mountain (金山)—which became the description for leaving for North America, Australia or New Zealand. “Gold Mountain” was not the name of a specific place; the Chinese had separate terms for “Canada,” the “United States” and “Australia.” Rather, it named a desire to seek your fortune far away across the seas.

The Canadian Head Tax Imposed on Chinese Immigrants

In 1885, the Canadian government imposed a $50 head tax on all Chinese entering Canada. Thousands of Chinese labourers had just built the British Columbia portion of the Canadian Pacific Railway, completed that same year, creating the transportation link that would now allow large numbers of European migrants to move westward across Canada.

The head tax imposed on arriving Chinese had been deliberately designed by the B.C. provincial government and the Canadian federal government to discourage Chinese migration and to raise revenue that would be split between the provincial and Canadian governments. A substantial proportion of a year’s wages as a labourer, the $50 tax was raised to $500 in 1904—the equivalent of almost two years of a worker’s earnings—and Canada raised over $23 million between 1885 and 1923, equal to over $1.5 billion in today’s dollars.

After imposing the head tax in 1885, the federal government created a detailed register that tracked not only who had paid, but also a variety of other details such as age, height, village of birth, county of birth, last place of residence, occupation, port of origin, place and date of arrival and registration, and ship’s name. After the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1923—officially known as the “Chinese Immigration Act” even though it was designed to stop Chinese immigration—everyone in Canada of Chinese ancestry, even those born in Canada, was forced to register and receive an identification card designating them as “alien.” People in Canada who were not residents did not receive such cards.

The Maps of Destinations in Canada and Origin in China

It is a great irony of the history of immigration to Canada that Chinese migrants—those who were most unwelcome—have given historians more detailed government data than the more welcomed immigrants from Europe. The maps in this kit are the result of that data being so detailed.

Between 1910 and 1949, the Head Tax register contained destinations for Chinese immigrants to Canada, with 35,680 individuals recording 460 unique destination cities and towns across Canada. These maps show where Chinese were headed after arrival (usually by ship to the Port of Vancouver), and how they rode the Canadian Pacific Railway that they helped build, to travel all the way across to the Maritimes. Many were joining relatives that had already come to Canada before 1910 and who had opened cafés/restaurants, general stores and laundries in almost every small town in Canada. Most of these migrants were young men planning to work hard and save enough money to get married and raise families. Sadly, because of discriminatory legislation such as the 1923 Chinese Exclusion Act, many were not able to achieve their dreams.

The maps show how many Chinese Canadians lived in small towns in each province, and how few Chinese were able to enter Canada after 1923. The maps also show how almost all of the migrants came from just a small area of southern China in Guangdong province (also historically called “Canton province,” for which their regional language of Cantonese is named).

Just eight small counties in Guangdong province made up 97 percent of the migrants to Canada in this period, and one single county, Taishan (or in their own county dialect, pronounced “Toisan” or “Hoisan”), accounted for almost 44 percent of all the migrants who came to Canada!

www3.onf.ca/sg2/Maps_Passage_Beyond_Fortune.pdf

Small-town Canada and Chinese Immigrants

Although there is a long history of anti-Chinese racism and discriminatory legislation against Chinese in Canada, many Chinese Canadians found that life in small towns was better than in the bigger cities. Running stores or restaurants or laundries in a small town meant Chinese Canadians provided a much appreciated service, and because they were a small minority of the community, they were not generally considered a threat. Some long-standing café owners became beloved members of the community, and some formed families through marriage with European immigrants or Indigenous women.

Online Resources

Use these resources to help students understand why Chinese cafés were an important part of small-town Canadian life, and how racism may have shaped the lives of Chinese living there in ways that were both similar to and different than the Chinese experience in larger cities.

The story of Noisy Jim, the long-time proprietor of the New Outlook Café, in Outlook, Saskatchewan, and how the town wanted him to become mayor. This moving film by Cheuk Kwan also details how important the Chinese cafés were to small-town life in Canada.

Canadian senator Lillian Dyck tells the story of being the daughter of a Chinese café owner in North Battleford, Saskatchewan, and the importance of understanding the story of her mother, an Indigenous woman who was Cree. She describes the vicious racism that Indigenous people faced and how it led to the choice by her mother to only identify their children as Chinese, believing they would face less racism. From UBC’s web series Chinese Canadian Stories.

For beautifully written short stories about his family and growing up in small towns across the Prairies and B.C. as a “mixed-race” child of a marriage between a Chinese café owner and a mother of mixed European ancestry, Canadian parliamentary poet laureate Fred Wah’s short-story collection Diamond Grill is haunting and humorous and captures the complexity of small-town Canadian life and the interplay between people of very different backgrounds.

Dr. Henry Yu’s research and teaching has been built around collaborations with local community organizations, civic institutions such as museums, and multiple levels of government. He is passionate about helping Canadians unlearn the cultural and historical legacies of colonialism, and inspired by the often hidden and untold stories of those who struggled against racism and made Canadian society more inclusive and just. He has served on advisory committees for formal apologies acknowledging historical discrimination and for the implementation of substantive legacy projects at all three levels of government.

Pour lire cet article en français, cliquez ici.

Discover more Mini-Lessons | Watch educational films on NFB Education | Watch educational playlists on NFB Education | Follow NFB Education on Facebook | Follow NFB Education on Pinterest | Subscribe to the NFB Education Newsletter