Unarchived: In the Eyes of Canada, We Were “Noteworthy”

Unarchived: In the Eyes of Canada, We Were “Noteworthy”

Unarchived opens the door to probe and introduce stories that make for a shared history of British Columbia and Canada. For the most part, the multiple stories told by the filmmakers are found in every community from coast to coast to coast—Indigenous, 2SLGBTQI+, South Asian Canadian and Chinese Canadian—yet have been overlooked.

Many museums and archives are having conversations about what and how stories are told, as well as who is doing the telling. In 2018, Heritage BC’s annual conference opened with a plenary, “(Re)Interpretation: Challenging the Narrative of Cultural Heritage.” Sharanjit Kaur Sandhra addressed colonial history in her 2020 BC Museums Association presentation, “#MuseumsAreNotNeutral: White Supremacy in Museums and Calls to Immediate Action.” In my hometown, the Nanaimo Museum offered its own version of reviewing and interrogating its collection in 2021 to offer new perspectives on the city’s history. Why were certain stories left out?

Unarchived, Hayley Gray & Elad Tzadok, provided by the National Film Board of Canada

As a community’s population ebbs and flows, its composition can change dramatically, especially if it’s reliant on resource extraction. Consider Cumberland, located on Vancouver Island; incorporated in 1898 as a city, it reverted to village status in 1958. On initial arrival, a new resident or visitor today might be shocked to learn that the village had a substantial East Asian population, with a Chinatown and two Japanese Towns. In comparing the population from the Sixth Census of Canada, 1921 with the Census Profile, Census 2016, Cumberland has not grown much (see Table 1); however, what is notable is the decline in numbers of those identified as Chinese and Japanese. With such a dip in numbers, who will remember these early racialized immigrant populations?

| Cumberland | 1921 | 2016 |

| Total | 3,176 | 3,753 |

| Chinese | 854 | 25 |

| Japanese | 409 | 15 |

Much can be learned from data available in the various census years. For example, within its six volumes, the 1921 Sixth Census of Canada considers topics including, though not limited to, racial origins, religions, birthplace, immigration, educational status, occupations and agriculture.

Government documents such as censuses can aid in the recovery of a general picture of a community. However, patience is needed for specifics. Perhaps you have a few clues: a name, a date, a location. Sizable early Chinese communities were often segregated from the larger town or city and enumerated as such in the census. This fact can aid in delimiting a search, as in Cumberland’s or Nanaimo’s Chinatown.

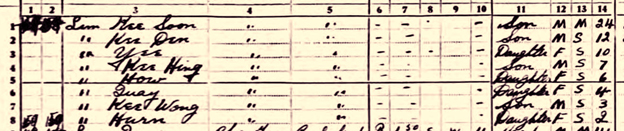

I have searched for my own family. In Figure 1 (below) are the names and ages of eight Lim siblings from the Sixth Census of Canada. These are my aunts and uncles, as well as my father, Kee Wong. A few facts can be useful to hone your quest. The challenge might be the actual name: perhaps the spelling is inconsistent, or you knew the family member by their English name. In my father’s case, his English name was Wilbert; I grew up thinking that Wong was his middle name. To find an ancestor might require leafing through page upon page of handwritten census details. The Vancouver Public Library’s guide to Chinese Canadian Genealogy offers excellent tips.

Census information can also serve as a myth-buster. While growing up, I always knew that my Canadian roots began in Cumberland. As well, I regularly heard from my elders that its Chinatown was the largest Chinese community north of San Francisco, with a population as high as 3,000. The iconic photograph of Cumberland’s Chinatown, circa 1910, was once pointed out to me as “proof” of the Chinese community’s size. Logic alone negates this possibility.

Cumberland was never sizable (see Table 1 above). According to my elders, the 1920s was the peak of Chinatown’s existence. It was large, but not the largest on the Island, nor in British Columbia (see Table 2 below). The 1911 Census does not have the same specificity as the one from 1921, that is, “origins” in the earlier census were limited to principal cities. Nevertheless, even in combining the numbers from Comox and Cumberland City, the total is less than Victoria’s Chinese population. Both are within the Comox-Atlin District, one of seven census districts. Chinese numbered 2,665 in the Comox-Atlin District, which is still no match for the city of Victoria (see Table 3 below).

| 1921 | Total Pop | Chinese male | female | Japanese male | female |

| Vancouver, BC | 117,217 | 5,899 | 585 | 2,529 |1,717 |

| Victoria, BC | 38,727 | 2,938 | 503 | 129 | 96 |

| New Westminster, BC | 14,495 | 702 | 45 | 247 | 177 |

| Nanaimo & Suburbs, BC | 9,088 | 379 | 54 | 16 | 4 |

| North Vancouver, BC | 7,652 | 94 | 1 | 55 | 34 |

| Prince Rupert, BC | 6,393 | 171 | 16 | 108 | 67 |

| Nelson, BC | 5,230 | 165 | 5 | 0 | 0 |

| Kamloops, BC | 4,501 | 164 | 9 | 7 | 5 |

| Fernie, BC | 4,343 | 68 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Vernon, BC | 3,685 | 136 | 31 | 5 | 2 |

| Cumberland, BC | 3,176 | 802 | 52 | 268 | 141 |

| Trail, BC | 3,020 | 44 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Revelstoke, BC | 2,782 | 92 | 7 | 120 | 10 |

| Cranbrook, BC | 2,725 | 10 | 0 | 13 | 7 |

| Kelowna, BC | 2,520 | 114 | 0 | 4 | 3 |

| 1911 | Chinese | Japanese |

| Comox | 1,185 | 387 |

| Cumberland city | 6 | 11 |

| Nanaimo city | 591 | 44 |

| Nanaimo suburbs | 16 | 1 |

| Victoria city | 3,458 | 182 |

However, Cumberland’s distinction isthat its Chinese population was more than 25 percent of the city’s total, while representation in other BC locations ranged from less than 1 percent (Cranbrook) to just under 9 percent (Victoria). By including Japanese, the Asian population is shy of 40 percent of Cumberland’s total. Neither the Village nor Chinatown descendants need to maintain a fiction about Chinatown’s size; Cumberland was unique regarding its “town within the city.” This noteworthy fact (population ratio) likely affected personal relationships. To this day, since 1975, there continues to be an annual Cumberland Chinatown Reunion in Vancouver.

Additional resources in recovering lost stories include business directories and/or fire insurance maps. Unfortunately, these are incomplete. The records are only as good as the foresight of an individual or institution in preserving them. Search the Library and Archives Canada site for fire insurance maps; under “Source” is listed “Government” (3) and “Private” (899). In the British Columbia Directory for 1884-85, under the listings of Victoria, Nanaimo, Wellington and New Westminster, as well as the Cariboo District, is the heading “Chinese Directory.” From this, a name, a business and a location can be salvaged from the past.

This is the reminder that communities need, besides government records, private collectors—a Ron Dutton or a Joan Mayo or a Catherine Clement—who capture the history of a place and time. Thanks to their dedication, ready access is available: BC Gay and Lesbian Archives, South Asian Canadian Digital Archive (Joan Mayo Fonds) and the Yucho Chow Community Archive, respectively. These are some of BC’s and Canada’s lesser told stories.

Access to government records matter, especially for the earliest Asian populations, who were impacted by racist policies. The 1921 census was a significant marker for both sides of my family. Grandfather Lim died in 1924; the family left Cumberland’s Chinatown in 1928, never to live there again. The Chan family (mother’s side) left Vancouver in 1930. This one census firmly establishes my Canadian roots.

With the regular enumeration of individuals as part of the census, we are and were “noteworthy.” The manner of interpretation and presentation can make a difference in perception and perspective; are the voices, especially of racialized and minority populations, being heard? As others have said, now is the time to be loud and proud.