The Hangman Is Looking for an Accomplice, and That Accomplice Is You

The Hangman Is Looking for an Accomplice, and That Accomplice Is You

The Hangman at Home is comfortable with the uncomfortable, which is probably par for the course when you base an animated short film on Carl Sandburg’s poem of the same name. The poem wonders about a hangman’s home life and how he manages to compartmentalize his morbid day job during family dinner. But even if the poem didn’t do any of that, the word “hangman” is already loaded with ghoulish significance, so when we hear it spoken within the first minute of the film’s narration, we’re already making associations with death, violence and the macabre.

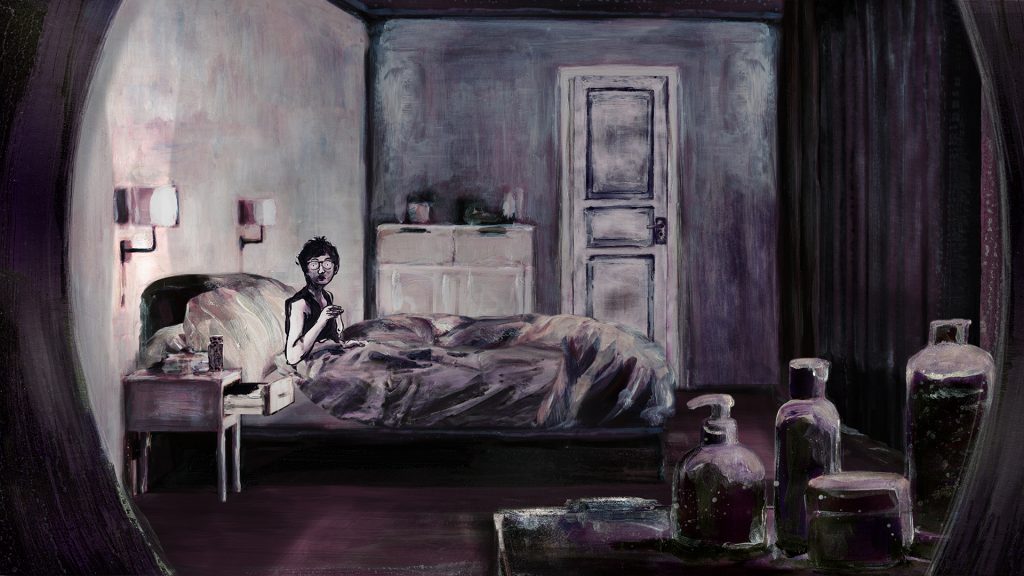

Directed by Michelle and Uri Kranot, Hangman unsettles the viewer with voyeurism and the uncanny. We peer into five different lives that are each at a unique crossroads. We eavesdrop on an elderly man who returns to what’s left of his war-ravaged home; a pregnant woman fleeing unseen oppressors; a teenager discovering his sexuality; a father and daughter playing horsey; and a man keeping vigil over a bed-ridden dying loved one. Some do ordinary things; others do forbidden things.

It almost feels like we’re watching them from a crack in the wall, which is intentional.

The Hangman at Home, Michelle Kranot & Uri Kranot, provided by the National Film Board of Canada

“We wanted to play with the feeling of, ‘Am I supposed to be here?’” said Uri. “As filmmakers, we invite you in, but the ambiguity of this awkward intimacy is meant to make the audience active and ask themselves these questions, instead of being passive witnesses to a situation.”

What makes it even more disconcerting is that what we see is not altogether unfamiliar. The Kranots used rotoscoping to capture the characters’ movements, which lends realism to what we witness. But the characters themselves are painted and not rendered in a photo-realistic way. And with their lidless round eyes, they sometimes look eerie, or at the very least alert.

This haunting mix of realism and fabrication is precisely the effect the Kranots were after, in part to alienate the viewer, but also to keep us guessing about the things we see, which are somewhat rooted in reality.

“We started with many more stories and slowly we distilled them to just five,” Uri told me. “Some of the stories are autobiographical, others are stories we heard of. All of them are deeply connected and dear to us.”

Meantime, Sandburg’s poem relentlessly vibrates in the background. It’s not directly related to the scenes that play out before us, but it’s not unconnected either. The poem talks about playing horse, and one of the stories shows us just that. But then there’s also the idea of home. The narration asks us to imagine that a hangman has a home to go to, and the film visually takes us inside different people’s homes. Could they be where the hangman lives? Or do they face the same grim challenge the poem imagines for the hangman? Are they also struggling to find safety within the walls that surround them, despite the chaos and destruction happening outside?

It tracks that the poem came before the stories because we sense that they were inspired by the former, as if they’re each independently working through Sandburg’s ideas.

“We intended to create a wide scope of characters,” Kranot said. “By placing them together, we hoped to achieve an identification with a human moment rather than a specific person or situation. We all share a moment together, connected by our humanity.”

To cement that connection, the characters look directly at us near the end of Hangman, acknowledging our presence and our complicity in their lives. It’s unnerving, but also not unwarranted. We’ve been involved in their stories indirectly; the end simply makes that involvement more explicit.

No one really knows what goes on behind closed doors, but Hangman does. It takes you to those secret places and makes it impossible for you to unknow what you saw.