Propaganda Cinema at the NFB – The World in Action

A few months back I wrote about the Canada Carries On series of propaganda films that were shot specifically for theatrical distribution in Canada during the early days of World War II. (You can read about this series here.)

These films were so successful that it was decided to produce a new series that would complement them by covering the war from a broader international point of view. This was The World in Action. John Grierson, the NFB’s film commissioner as well as the head of the Wartime Information Board, envisaged a series for domestic and international audiences that would present the global strategy of the war. Patterned after the very popular American March of Time newsreels, The World in Action would have a Canadian view of things but would deal with international themes.

Grierson had obtained official access to all British and American film material as well as enemy footage intercepted by the Navy. Ottawa became the allied war repository for film material for the duration of the war.

With access to all this great material, one key thing remained to be done: find a distributor in the important American market. In early 1942, Grierson went to Hollywood and met with Charlie Chaplin and Mary Pickford of United Artists (UA). He convinced them of the importance of distributing these films. UA agreed, and a deal was made to distribute the first twelve issues throughout Canada, the USA and Great Britain. Stuart Legg was brought over from Canada Carries On to produce the new series. Lorne Greene narrated the films in his own inimitable style.

The very first issue, Inside Fighting Russia (a.k.a. Our Russian Ally), ran into trouble immediately. UA would not distribute it in the United States as they considered it to be communist propaganda. The film is a look at the Soviet Union’s fight against the Nazis. While well-intentioned, the film lays it on a bit thick as to the strength and power of the Soviet people. The view presented of the communist system is naively oversimplified. While the USA and Soviets were fighting a common enemy, America’s mistrust of communism could not be dispelled so easily.

After this unfortunate start, the films started appearing in theatres about once a month. They would screen in 6,000 cinemas stateside and 1,000 in Great Britain, being seen by 3 million people in the USA alone. In Canada 23 copies in English would be released to theatres with a further two copies going out in French. These would circulate for about six months throughout the country.

Controversy dogged this series from beginning to end. The January 1945 issue Balkan Powder Keg was released in three theatres in Canada before being pulled. The Canadian Government forced the withdrawal after complaints from British Prime Minister Winston Churchill. The British did not appreciate the criticism of their foreign policy in the Balkans as seen in the film. The whole thing was eventually cut down to 10 minutes and released in December 1945 after the war was over under the title Spotlight on the Balkans, basically a watered-down version of the original. Surprisingly, a shot of nude exotic dancers in Bucharest was retained in the new version. How this slipped by the censors is beyond me.

Spotlight on the Balkans, , provided by the National Film Board of Canada

Sadly, very little of the horror of war was shown in these films. There was next to nothing about the persecution of Jews and other peoples by the Nazis. This was at the request of the government ,who wanted to avoid an influx of refugees from the conquered countries of Europe. Only at the very end of the war was the Holocaust hinted at in these films, but by then it was much too late to do anything about it.

Seven issues from the Canada Carries On series were also released as part of The World in Action, including the first Canadian Oscar®-winner Churchill’s Island as well as Warclouds in the Pacific and Corvette Port Arthur, directed by Dutch documentary filmmaker Joris Ivens.

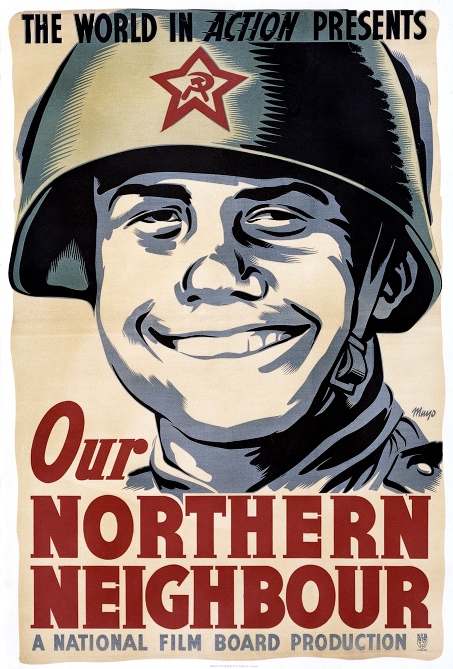

As with Canada Carries On, some of the films were versioned into French and released in Quebec and New Brunswick as Le Monde en Action. One of these, Our Northern Neighbour, another film looking at the Soviet Union, was banned by the Quebec Censor Board as it was felt that the film was communist propaganda. Censorship was closely tied with the church in Quebec, and it was felt that communism was against everything the church stood for. The NFB tried to appeal the ban to no avail.

Our Northern Neighbour , Tom Daly, provided by the National Film Board of Canada

Once the films completed their theatrical run, they would continue in the non-theatrical market, playing as part of NFB film programs in schools, factories, church basements and service clubs. Copies were made on the more portable 16-mm film stock for these showings. Travelling projectionists, trained by the NFB, would play the films in as many small towns and rural areas as possible from coast to coast. The projectionists would supply their own 16-mm projectors and electric generators on their travels. There were about 250 travelling projectionists in 1945. This number would drop significantly once the war ended.

Unlike Canada Carries On, which continued production well after the war ended, The World in Action was stopped in 1945. Some 30 odd titles were produced in all, over a three-year period. One of the last films in the series, Now the Peace (released in May 1945), focused on the creation of the United Nations and its role in helping shape the post-war world. With the war at an end, a few more issues were produced until the series was suspended. UA pulled the plug on distributing these films in the important American market leaving the NFB no choice but to end production.

The films in this series were the first Canadian films to receive extensive exposure throughout the world and more specifically in the United States. They served their purpose in educating and informing people about Canada’s view of the war. They were very well received and helped cement the NFB’s reputation as a producer of solid, professionally produced documentaries.

-

Pingback: The Mask of Nippon - Enemy in the Mirror

-

Pingback: The Mask of Nippon - 1942 - Enemy in the Mirror

-

Pingback: Balkan Powder Keg: Controversy, Censorship and the Missing Film | NFB.ca blog

-

Pingback: Churchill’s Island: The National Film Board’s First Oscar Winner | NFB.ca blog