Where Bear 71 Came From

Where Bear 71 Came From

The following is a guest post from filmmaker and creator Leanne Allison about the interactive documentary Bear 71.

***

We’ve all heard of the “elevator pitch”—a 30-second sell of a project idea to prospective producers. This is a story about one that worked and went on to become a high-profile National Film Board interactive documentary called Bear 71.

The pitch literally took place in an elevator, on my way to get a coffee with Rob McLaughlin, who was then head of the digital program at the NFB. After I showed him only a dozen or so trail-cam photos and explained where they came from, he paused for a moment, looked at me and said, “You’ve got a winner here, Leanne. Good work.”

I told that story recently to Jeremy Mendes (co-creator of Bear 71) and asked him if he thought I’d have even been able to access Rob that day if it weren’t for my previous NFB film, Being Caribou. Jeremy said, “If it weren’t for Being Caribou, you wouldn’t have seen that there was a story in all those images in the first place.” He’s right of course, but it wasn’t until then that I connected the dots myself.

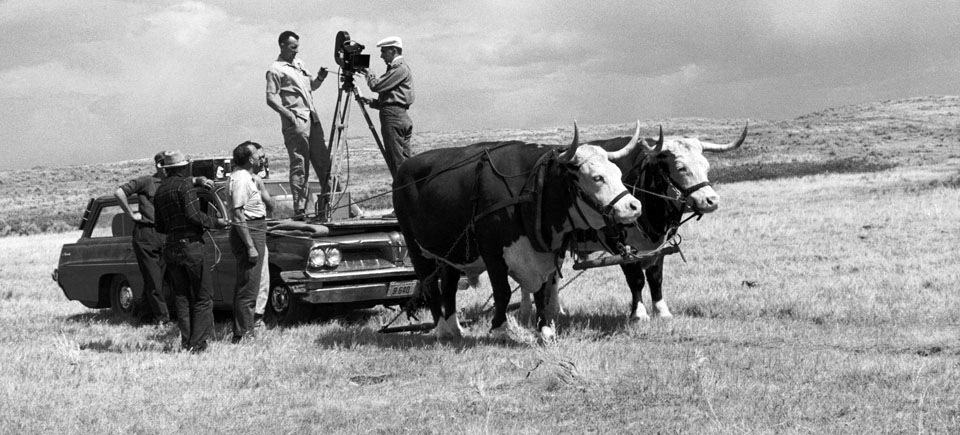

Being Caribou is about a journey my husband, Karsten Heuer, and I did in 2003, when we followed a herd of 123,000 caribou on foot during their annual migration from the central Yukon to the Alaska coast and back. What made the trip unique was that we couldn’t have a route plan; everything was left up to the caribou, including where we went and for how long. During the 5-month journey we didn’t cross a single road or pipeline and only encountered a handful of people. We were constantly in the presence of wild animals such as wolves, wolverines, musk ox, eagles and foxes, because the caribou tow an entire ecosystem with them on their migration. This immersion in an ancient animal rhythm made us wake up to an old way of being human. We started to dream about where we would see caribou next, and to guide us we used a sound Karsten describes as “thrumming” in his book about the trip. It was something you felt more than you heard, and yet we trusted this new sense, and it worked. Reconciling that world we discovered with the caribou and the busy modern world we have since returned to has been difficult. In a way, we’re always searching for a path back to what we discovered with the caribou.

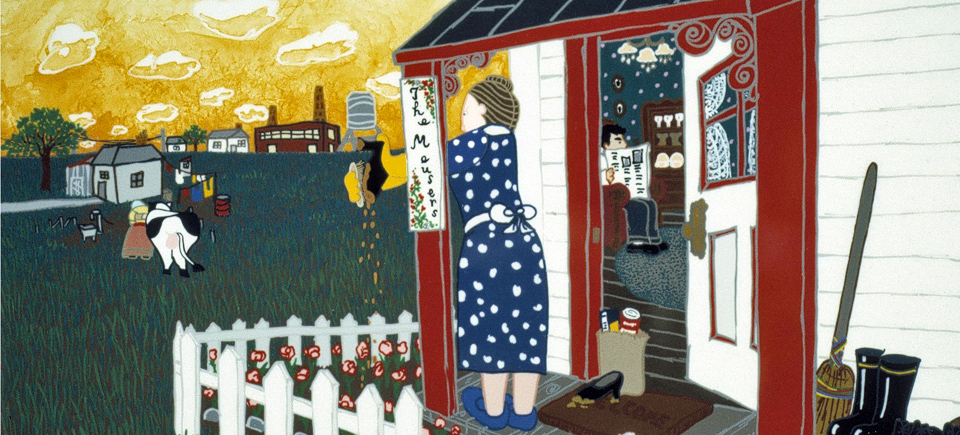

Not long after that trip, we started a family, and when our son Zev was 2 and a half it was time for another adventure. This time it was inspired by stories, some of them written a half century ago by one of Canada’s most famous writers, Farley Mowat. It was another 5-month journey that took us canoeing and sailing across Canada through the settings of some of Mowat’s most famous tales. Sure enough we found his stories intact and still connected to the landscapes in which they were written, making us wonder whether we really write these stories, or whether they’ve been there all along and “release” themselves to those who take the time to notice them.

While the Finding Farley film was having its debut on the festival circuit, I was starting to wonder what the next project was going to be. Some interactive projects were circulating at the NFB, and one in particular made a big impression on me. Jonathan Harris’s The Whale Hunt is a photographic experiment in storytelling that allows users to sift through his 5,000 photographs of a whale hunt from any perspective they choose—even that of the whales. After seeing this, the light bulb went off, and I knew I had a home for the thousands and thousands of trail-cam photos taken for research purposes where I live, in the Bow Valley of Alberta. I’d known about the photos for several years and had always been fascinated by them, but I knew they’d never hold up to the big screen since the images are very low resolution. This was a small-screen project, perfect for interactive web-based media.

I spent a few months poring over thousands of photos, trying to figure out what the story was going to be about. After any given session spent in front of my computer going through hundreds of images of wildlife, I’d look out my window and see where I lived in a completely different way. I could imagine a cougar slinking by just a kilometre from my house, a wolf pack on a kill a valley or two away, or a grizzly bear scratching himself on a rub tree on a popular hiking trail just outside the town of Banff. The photographs showed me a world of animals, the same world we knew among the caribou, only now it was right in my backyard!

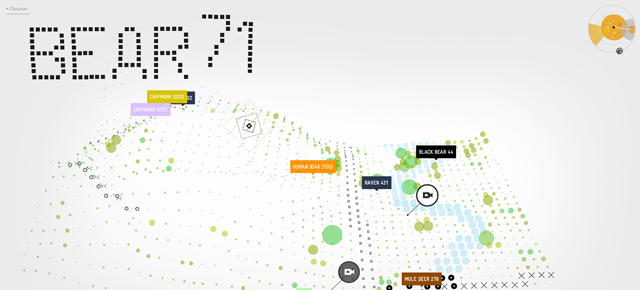

Right around this time Jeremy Mendes, a digital media creator at the NFB, offered to come on board the project to help me translate the story to an interactive platform. He, too, was excited about the potential of the grainy photos of wild animals taken with no one behind the camera, but what struck him was how much they looked like the surveillance photos taken of us every day at bank machines and 7-Eleven stores. And wasn’t it odd that we were looking at nature through the same lens?

That was when Bear 71 became a story not only about a grizzly bear, but about how much we rely on technology—not just to relate to each other, but also to the natural world. From that point onwards, many hours were poured into the project by many talented people to create the digital world of Bear 71, the interactivity, the script, the voice-over of Bear 71, the sound design, and everything else.

For me, Bear 71 is first and foremost a tragedy about an incredible mother grizzly bear who learns to navigate the maze of development in the Bow Valley only to be struck dead by a train. Secondly, it is a critique of technology via technology, highlighting how our reliance on it comes at a cost. We get further and further from our instincts, we forget about the thrumming, and our world becomes bound by computer screens instead of unbound by the sky above our heads. I’m lucky enough to know what I’m missing while sitting in front of this computer. After you’ve watched Bear 71, I’m hopeful you will too.

-

Pingback: Bear 71 VR now online | On Screen Manitoba