The Life and Times of Evelyn Lambart

The Life and Times of Evelyn Lambart

The launch of Donald McWilliams’s film Eleven Moving Moments with Evelyn Lambart (2017) affords us a fine opportunity to revisit the journey of this exceptional artist. The first female animation filmmaker in the country, Evelyn Lambart enjoyed a prolific career marked by passion and invention.

A difficult childhood

At age six, Evelyn began to experience hearing loss. The condition quickly deteriorated, and within a few years she was nearly deaf. Her parents encouraged her to explore drawing and painting, pursuits that did not depend on her hearing. She developed a taste for and remarkable skill at both art forms, which would serve her well in later years. But her childhood was challenging: she did not have the benefit of a hearing aid, and her teachers failed to take her handicap into account. Evelyn was soon isolated from her classmates and felt excluded from society. In spite of these challenges, she vowed to never be left out, eventually find a job, never marry, and live life to the fullest. At the National Film Board, she would find her place in the sun.

Early days at the Film Board

In 1939, at the behest of the federal government, John Grierson founded the NFB, setting up its headquarters in Ottawa, the city of Evelyn’s birth. Mere months later, the world was at war, and the fledgling organization busied itself producing propaganda films. Starting from scratch, with means and methods still to be devised, Grierson threw the doors of the institution open to new Canadian talents.

It was against this backdrop that Evelyn, her Ontario College of Art diploma in hand, knocked on the doors of the Film Board one day in 1942, looking for work. Norman Mclaren offered her the opportunity to join his small team of animators. She first worked in the title department, but when it became clear she wasn’t particularly fond of lettering, she was asked to animate the maps featured in the documentary series The World in Action. She employed the paint-on-glass method, a technique with which she would later display virtuosic ability.

After World War II, she made her first film, The Impossible Map (1947), an educational short that brilliantly illustrated the difficulty—indeed the impossibility—of accurately projecting the spherical surface of the Earth onto a flat surface, a problem she had tackled many times when painting maps on glass.

The Impossible Map, Evelyn Lambart, provided by the National Film Board of Canada

Collaboration with Norman McLaren (1944–1965)

For more than twenty years, Evelyn Lambart worked closely with Norman McLaren. She began as his assistant, and their collaboration soon grew into a true partnership that saw her credited as co-director of the films they developed together. McLaren owed Evelyn a great deal: she displayed uncommon practical wisdom and prodigious dexterity—two qualities that made her an indispensable colleague. With McLaren, she co-directed the superb Rythmetic (1956), Lines: Vertical (1960), Lines: Horizontal (1962) and Mosaic (1965). But their greatest work, inarguably, was Begone Dull Care (1949).

Begone Dull Care , Norman McLaren & Evelyn Lambart, provided by the National Film Board of Canada

During this period, Evelyn also animated the titular piece of furniture in the Oscar®-nominated A Chairy Tale (1957), co-directed by McLaren and Claude Jutra. In addition, she helped animate Le Merle (1958), a little gem of a film that used paper cutout animation, a technique that she would go on to employ in her own films. Working on McLaren’s Now Is the Time (1951), Around Is Around (1951) and Twirligig (1952), she helped pioneer stereoscopic (3D) animation. She also assisted McLaren with development of a card system for synthetic sound, and perfected an apparatus for photographing his synthetic notes.

Her own films

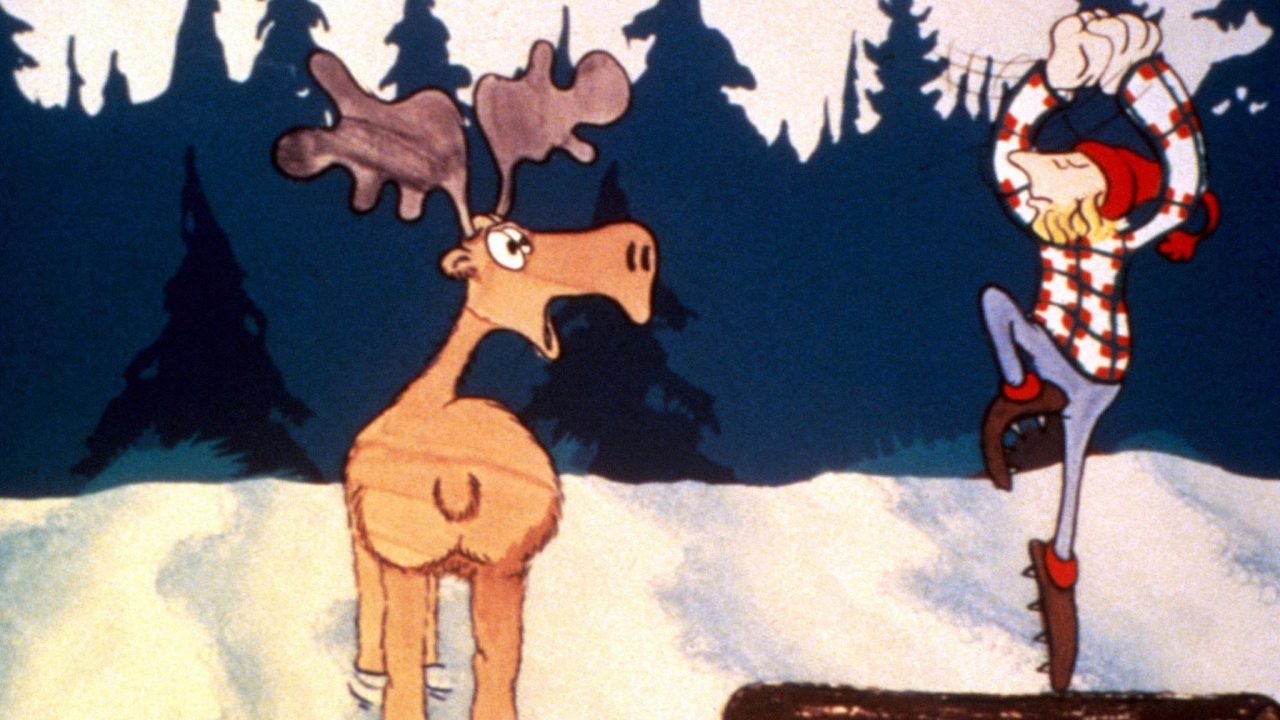

By the late 1960s, Evelyn was focused entirely on her own creations, producing magnificent, delicately fashioned and colourful films for children. These relied on paper cutout animation, a complex technique that allowed her to not only impart precise movements to her characters, but to have them express all manner of emotions. She was responsible for every creative aspect of her films: story, character design, painting, drawing, and animation under the camera. Her films from this period include Fine Feathers (1968), The Hoarder (1969) and Mr. Frog Went A-Courting (1974).

Mr. Frog Went A-Courting, Evelyn Lambart, provided by the National Film Board of Canada

In 1974, she retired to her country home in Knowlton, in the Eastern Townships, after a thirty-year career at the Film Board. Away from the company of people—preferring that of plants and animals—she made her last two films, The Lion and the Mouse (1976) and The Town Mouse and the Country Mouse (1980). Evelyn Lambart died in 1999, aged ninety-four.

The Lion and the Mouse, Evelyn Lambart, provided by the National Film Board of Canada

An artist in her own right

Evelyn Lambart’s contributions to Canadian animation are colossal. Literally the “First Lady of Canadian Animation,” she paved the way for women’s presence in a milieu where men make up the majority to this day. A gifted artist, an impassioned, inventive filmmaker, she leaves a body of work that has too often been linked to that of Norman McLaren. It is high time we acknowledged her rightful place!

Eleven Moving Moments with Evelyn Lambart, Donald McWilliams, provided by the National Film Board of Canada

Has anyone viewed Evelyn’s collection of photographic slides at Library and Archives? There are a ton and they are very well organized, with a hand written index she wrote, soma pages on NFB stationary. Some great photos of Stewart Street, Ottawa, Blue Sea Lake, Lake Bernard, her and her family, Canada Day in Ottawa in the late 30’s, Quebec City, Kingston, Toronto and so much more. Quite an amazing collection.