Himalaya Blues: A Song for Tibet

Himalaya Blues: A Song for Tibet

Two weeks ago was World Refugee Day. Celebrated June 20th, this day was established by the United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR) to help the public empathize with and understand the dilemma of refugees, who must choose – often over and over – between staying and risking their lives in a conflict, or risking kidnapping, rape, torture or worse if they flee. Refugees aren’t a marginal problem. It is estimated there are over 40 million refugees or forcibly displaced persons worldwide. (80% of those are women and children.)

That day, I was moved by a World Refugee Day special on The Big Picture, one of my favourite photo blogs. An online property of The Boston Globe, The Big Picture illustrates news stories in photographs, and does so excellently.

Among photos of Afghan, Syrian, Palestinian and Sudanese refugees, I saw pictures of another refugee group I hadn’t been expecting: Tibetans.

Right, I thought. Tibetans. Thousands of them have fled – and continue to flee – Tibet since their land was incorporated into the People’s Republic of China, in 1959. (It is estimated that 1 million Tibetans died in that annexation process.)

Today, Tibetans live “in exile” all over the world. Many, like the 350 Tibetans living in the Katmandu refugee camp pictured in The Big Picture, have emigrated to neighbouring Asian nations. Others have gone further: Canada is said to hold one of the largest concentrations of Tibetans outside of Asia.

We have a great documentary about these Tibetan Canadians and their struggle to safeguard and promote their cultural and religious traditions, which they fear are dying inside Tibet at the hand of the Chinese.

The film, titled A Song for Tibet, follows a man and a young woman to Dharamsala, India, home of the current Dalai Lama and the exiled Tibetan government, and back to Montreal, where the Nobel Peace Prize is due for a visit.

The man is an activist as well as the founder of a performing arts group whose mission is to safeguard the songs and dances of Tibet. He was 9 years old when he last saw the Sacred Kingdom.

The young woman accompanying him was born in Canada, on the South shore of Montreal, to 2 Tibetan parents ardently committed to defending their ancestral traditions. Together, they fly to India to connect with their roots, albeit transplanted ones.

There, they talk to a few exiled Tibetans, and we hear their stories. A woman, who fled Tibet after she was detained and tortured for carrying a picture of the Dalai Lama, says the authorities forced her to undergo abortions and killed her father. A small boy, 9, asked what he remembers of Tibet answers: “I remember my mom and dad.”

After being shown (gruesome) footage of a raid on a monastery shot by Chinese police and smuggled into India, we speak with a young monk. He tells us that after he testified before the UN on the subject of human rights abuse in Tibet, his own mother was beaten to death. That’s why it’s generally monks and nuns you see leading demonstrations, he says. Because if they die, they don’t leave many behind. (Monks and nuns don’t have children.)

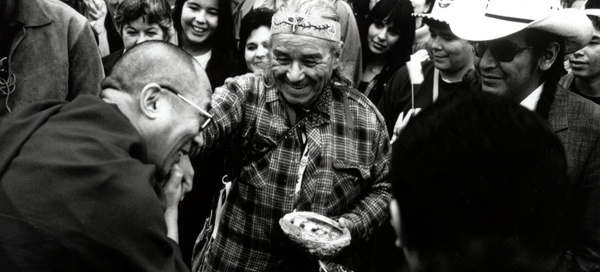

The second half of the film, which sees the 2 travellers back in Montreal, is more uplifting. There’s ample footage of the Dalai Lama, for starters, and if you know anything about the Dalai Lama, you know his face always sports a contagious, mischievous smile. Addressing a crowd in Montreal, he says some people think the fundamental nature of humans is aggression. “I still think it’s compassion”, he says.

Additional relief is brought via the reunion, sweet and long-delayed, of the young woman’s mother with her only sister. After she fled their village, the mother wrote her sister repeatedly, without ever hearing back. She ignored whether her sister was dead or alive. It turns out the letters had never reached their destination. The Chinese had renamed the village.

A Song For Tibet was released 21 years ago, but nothing in the news coming out of Tibet lately suggests that things have dramatically improved there. Since March 2011, more than 30 Tibetans inside Tibet are known to have set themselves on fire to protest the Chinese occupation. A large number of them were Buddhist monks.

A Song for Tibet, Anne Henderson, provided by the National Film Board of Canada