Now Online! Discover Our Indigenous Cinema Collection

Now Online! Discover Our Indigenous Cinema Collection

On March 22, the NFB launches a new Web page, bringing together 130 titles in English and 90 titles in French from our unparalleled collection of films by Indigenous directors.

VIEW THE INDIGENOUS CINEMA PAGE

Since 1968, the NFB has produced close to 300 films by First Nation, Inuit and Métis directors from right across Canada, offering original and timely perspectives on our country, our history and possible futures from a range of Indigenous perspectives.

Titles include Willie Dunn’s The Ballad of Crowfoot (1968), the first film made at the NFB by an Indigenous director. Sometimes referred to as Canada’s first music video, this short is a powerful look at colonial betrayals told through a ballad composed by Dunn himself about the legendary 19th-century Siksika (Blackfoot) chief. Dunn was a well-known musician on Canada’s folk music scene and a member of the Indian Film Crew—an all-Indigenous film production unit formed at the NFB in 1967. You’ll find other groundbreaking IFC titles like Mike Kanentakeron Mitchell’s You Are on Indian Land (1969), a short documentary that resonated strongly with 1960s civil-rights activists and travelled widely across Canada and the United States, including a famous screening at Alcatraz during the occupation of the infamous prison by members of the American Indian Movement; and Willie Dunn and Martin Defalco’s smouldering documentary The Other Side of the Ledger: An Indian View of the Hudson’s Bay Company (1970)—you’ll never think about the famous retailer in the same way again.

The Ballad of Crowfoot, Willie Dunn, provided by the National Film Board of Canada

You will also find several titles from legendary Abenaki director Alanis Obomsawin’s considerable opus, including Christmas at Moose Factory (1971), her very first film, created with children attending a residential school in the northern Ontario town of Moose Factory; and landmark films such as Incident at Restigouche (1984), which documented two police raids on the Mi’kmaq community of Restigouche in the early 1980s, and Kanehsatake: 270 Years of Resistance (1993), Obomsawin’s feature documentary about the 1990 Oka standoff, which was shot over 78 days behind Kanien’kéhaka lines and provides a privileged insider perspective on the historic conflict. The film reverberated around the globe and made history at the Toronto International Film Festival, where it became the first documentary ever to win the Best Canadian Feature Award.

Incident at Restigouche , Alanis Obomsawin, provided by the National Film Board of Canada

The selection also includes other essential titles by leading Indigenous directors, like Foster Child (1987) and Totem: The Return of the G’psgolox Pole (2003), both by the late Métis director Gil Cardinal; Hands of History (1994) by Loretta Todd; Two Worlds Colliding (2004) by Tasha Hubbard; If the Weather Permits (2003) by Elisapie Isaac; and Finding Dawn (2006) by Christine Welsh.

Totem: The Return of the G’psgolox Pole, Gil Cardinal, provided by the National Film Board of Canada

You can also explore recent titles like Nowhere Land (2015), by Inuk director Bonnie Ammaaq, winner of the Best Short Documentary award at imagineNATIVE in 2016; this river (2016), by celebrated Métis author Katherena Vermette and Erika MacPherson, which won Best Short Doc at the Canadian Screen Awards in 2017; Thérèse Ottawa’s award-winning short Red Path (2015); Mobilize, by multi-talented visual artist Caroline Monnet; and We Can’t Make the Same Mistake Twice (2016), by Alanis Obomsawin.

Mobilize, Caroline Monnet, provided by the National Film Board of Canada

In creating this online destination, our goal was to make it easier for audiences to find films that present Indigenous perspectives on Canadian realities. The site includes biographies for each of the directors and allows users to search for films by the nation/people of the director or the nation/people depicted in the film. Our educational team has also created curated playlists for different age levels.

The collection has been catalogued using the Indigenous Materials Classification Schema (IMCS) developed by Camille Callison (Tahltan Nation), Alissa Cherry and Keshav Mukunda which was first implemented at the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation (NCTR) Reference Library in 2015. Camille worked in collaboration with NFB Senior Librarian, Katherine Kasirer to adapt the IMSC for the NFB collection. As described by Callison, “the IMCS is based on the framework of the Brian Deer Classification system first developed by Kanien’kéhaka (Mohawk) librarian, Brian Deer, in the 1970s that was further adapted by Xwi7xwa Library and Union of BC Indian Chiefs (UBCIC). The IMCS is unique and was founded with the goal of reflecting indigenous worldview and values in knowledge organization. It is an adaptable open source classification schema that reflects best practices in organizing Indigenous knowledge and meet the needs of those seeking information on Indigenous (First Nations, Metis and Inuit) people.” To find out more about this groundbreaking classification schema, check out the links provided at the end of this blog post.

In 2017, the NFB launched a three-year plan to transform relationships with Indigenous creators and audiences within the context of its role as a public producer and distributor. As a public institution with a mandate to reflect the lives, experiences and perspectives of all Canadians though the works we produce, the NFB has a role to play in the national project of reconciliation.

In its final report, Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission underlined the critical role of culture in expanding our understanding of ourselves and our history, exposing truths and laying the groundwork for renewed relationships between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Canadians: “Creative expression can play a vital role in this national reconciliation, providing alternative voices, vehicles and venues for expressing historical truths and present hopes.” Our hope is that this site can play a small part in that process.

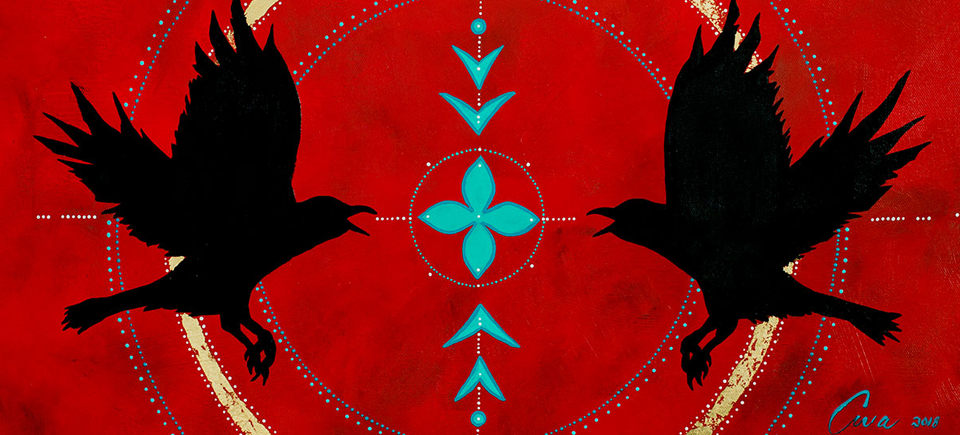

The homepage design is based on an original painting by Eruoma Awashish, a graphic artist from the Atikamekw community of Opitciwan. The painting depicts Kakakew, the raven—a recurring character in Awashish’s work. Kakakew is the messenger. “If we take the time to listen to him,” Awashish writes, “he is here to tell us things.” The flowers in the design are Atikamekw motifs that typically adorn bark baskets, canoes, embroidered moccasins, mittens and different clothes. “I integrate them in my painting to honour my culture,” says Awashish.

Many of the films in this collection are currently being screened in communities right across Canada as part of the Aabiziingwashi (Wide Awake) Indigenous cinema screening series. Since its launch in April 2017, there have been over 700 community screenings in every Canadian province and territory.

In coming weeks, new titles will be added to this site, and eventually our full collection of Indigenous-directed works will be available for free. We hope you enjoy exploring the films featured here and that you will come back often!

VIEW THE INDIGENOUS CINEMA PAGE

To learn more :

As a non FirstNations, I have always been concerned since childhood that we do not know the extent of oppression, racism, and disenfranchisement white powerful stakeholders have had on all First Nations. I look forward to viewing the resources drawn together by NFB to increase my knowledge.