World car-free day and Mobility in the developing world | Curator’s Perspective

World car-free day and Mobility in the developing world | Curator’s Perspective

Chances are, when someone tells you they’ve moved to a new house or apartment, the first thing you’ll ask them about is their commute. In Canada (like elsewhere in the industrialized world) we are obsessed with just how long it takes to get to our places of work. Do we travel by commuter train or public bus, or is it simply easier to take our car and face brutal traffic twice a day?

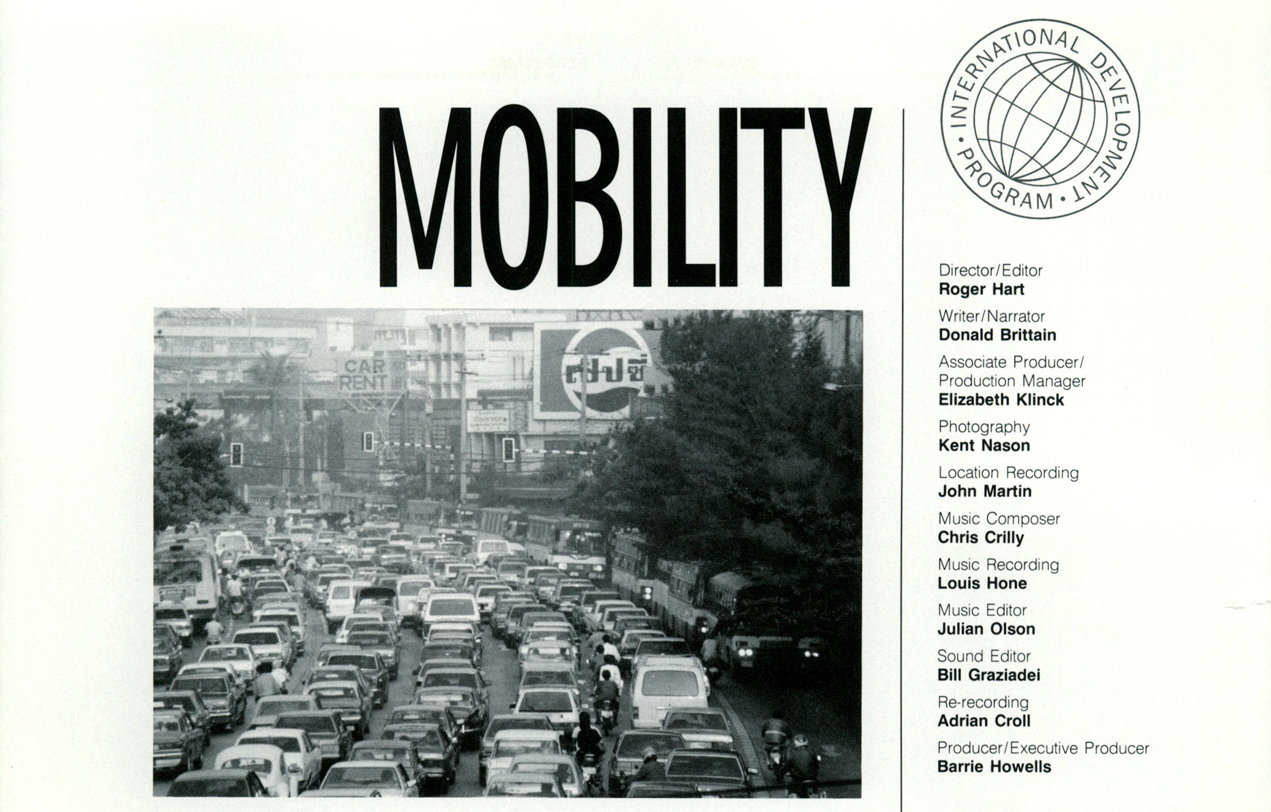

September 22 is World Car-Free Day, so I thought it would be a great occasion to present to you the NFB doc Mobility, which takes a look at public transit in the urban centres of several developing countries. Although it was produced in 1986, it’s an excellent introduction to the problems and solutions of transportation in the developing world. If you thought your commute was difficult, wait until you see how challenging it is in some of these cities. (Actually, many of them have come up with innovative solutions to their transportation needs.)

In Canada, we have very efficient transit systems (regardless of what many people will tell you). They fall into three categories: commuter trains, metro systems and buses. These are well-oiled systems with precise schedules and large fleets. They’re also very expensive and require large government subsidies to run efficiently.

But what about countries where there’s very little money to spare? Where purchasing a bus ticket is beyond the means of most people? They must come up with inventive solutions to be able to serve the poorest people (who need the services the most).

Solution 1: Mini buses

In Nairobi, the public system is simply too expensive for the average person (and there are not enough buses). It was created by the British to serve a small, white, middle-class population—unfortunately not the people who needed it most. It took resourceful local business people to realize that mini-buses (called matatus) were the solution. They charge minimal fares and their routes are flexible. That flexibility is the key. They can get the poor from the outlying areas to the city proper quickly and for only a small fee. The matatus are also built in Nairobi, providing work for the local population.

Solution 2: A huge fleet of buses

In Mumbai, size is the only way to go. As the film notes, some 2,300 buses service the city’s eight million inhabitants (now 12 million). The efficiency of the bus system is vital in preventing the city from descending into chaos. A training school in Mumbai ensures that the fleet is well maintained, as a lack of buses on the road would mean delays and gridlock. The system is very efficient, with as many as 93% of its buses rolling on any given day. There are also 900 trains per day going through Mumbai’s British-built Victoria terminus, moving an astounding two million passengers every 24 hours! Clearly this is a city that needs to be as organized as possible to keep functioning.

Mobility, Roger Hart, provided by the National Film Board of Canada

Solution 3: Dedicated bus lanes

Five thousand buses (the third-largest fleet in the world) service the city of Bangkok, which also makes very efficient use of motorcycles, ferry boats and auto-rickshaws (called tuk-tuks) to move people around in the oppressive heat and humidity. There are a growing number of cars on the road, which does not bode well for the city. Exclusive bus lanes have been created in an effort to alleviate traffic (which is like nothing I’ve ever seen before). If the growing middle class keep buying cars, the city will have to find other creative ways to get people around.

Porto Alegre, Brazil, is another city that has implemented exclusive bus lanes, especially in its downtown core, tremendously improving the efficiency of the service. In this case, there are several bus companies that work together to keep things running.

Solution 4: Keep it simple

Trivandrum, located in Kerala in the south of India, also uses auto-rickshaws to get people around. They don’t take up much room and can transport commuters quickly and cheaply. The city planners also take the needs of the poor into consideration before making any changes. Instead of having the poor run all over the city to access services, they’re brought to the areas in which the poor live.

As Mobility points out, the intentions of industrialized countries are often noble. They truly want to help those in the developing world, but too often it’s to sell them a mode of transport that’s not adapted to the needs of the people. The film points out that the World Bank doesn’t put a high priority on metro systems. They are ridiculously expensive to build and maintain, and their routes cannot be changed. Instead, simple and flexible modes of transport are encouraged. From walking to cycling to auto-rickshaws, the key is to use the mode that’s best suited to the needs of the people. Buses and rail systems have their uses, but it’s often better to keep it simple.

I invite you to watch this fascinating film. At the very least it will make you appreciate our modern transit systems. And it might even get you to think differently about how you get around.

Enjoy the film.

Mobility, Roger Hart, provided by the National Film Board of Canada

🚏 Enjoy more films about urban transit here.