Mini-Lesson for Minoru: Memory of Exile

Mini-Lesson for Minoru: Memory of Exile

Mini-Lesson for Minoru: Memory of Exile – The Japanese Internment and Generational Identity

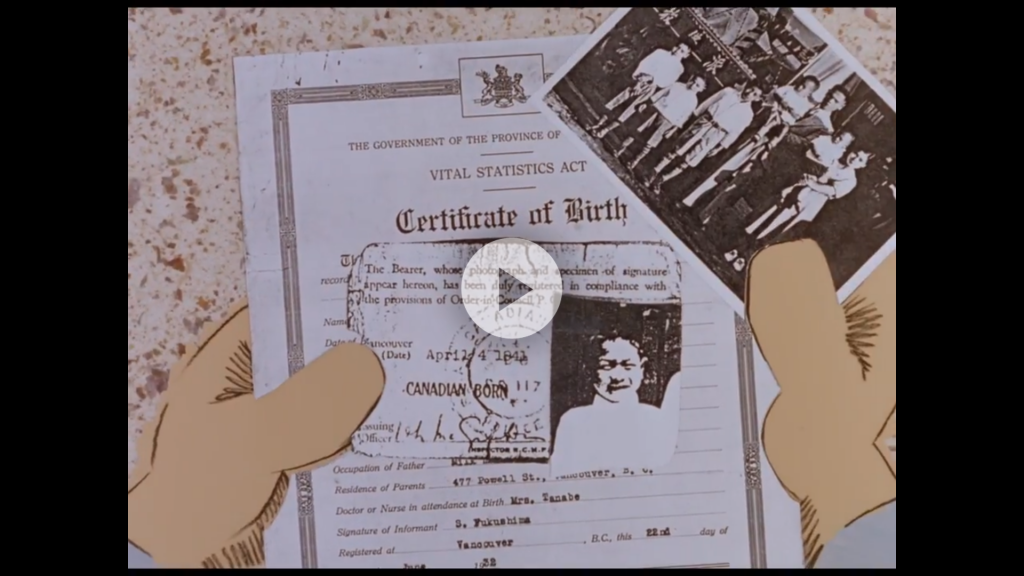

Most Canadians know about Japanese internment camps during World War II yet very little about Japanese-Canadians repatriated to Japan after the war. Why did these repatriations happen, and could something like this happen again?

Themes:

- Civics/Citizenship – Human Rights

- History and Civil Rights Education – Civil Rights and Freedoms

- Social Studies – Social Policies and Programs

Ages: 15-17

Minoru: Memory of Exile, Michael Fukushima, provided by the National Film Board of Canada

Guiding Question: How did institutional racism affect the lives of members of the Japanese-Canadian community in British Columbia during and after World War II?

Contextualize: Before you watch, think about the patterns that historians recognize in societies in conflict. We see this in the world today where a vulnerable group is identified, “othered” and then persecuted for their differences and the perceived threat they pose to the majority.

Activity #1

Have students address what they consider to be the main cause for the internment of Japanese-Canadians. Post each of the following on a separate wall of the classroom to allow for students to discuss their choice in small groups and then with the entire class:

- Anti-Asian sentiment that predated World War II

- Wartime paranoia/fear for Canada’s national security

- Public pressure from residents of British Columbia

- Resentment of Japanese-Canadian fishermen who posed an economic threat to Canadian fishermen

Justify your answer.

Go Deeper

Japanese-Canadians lost their homes, cars and personal belongings. When they were removed from their homes, they were only allowed to bring a limited allowance of items to the internment camps. Men were separated from their families; women and children lived in squalid and shared accommodations with other families. Anything that had to be left behind was sold at a fraction of its value to pay for the costs associated with their owners’ internment.

Four months after the end of the war, the government of Mackenzie King announced that “for the security of all Canadians,” all naturalized Japanese would be “repatriated”: deported back to their country of origin.

Activity #2

After the bombing of Hiroshima, the difficulties for Japanese-Canadians were far from over. The choice for Grandfather Fukushima was between “a country that would never accept him or a Japan barely remembered after 25 years in Canada.” Those who returned to Japan experienced further displacement and culture shock. How had this group been “exiled” again?

Go Deeper

By January 24, 1947, Canada had cancelled deportation orders for the Japanese. To not rescind these orders would have been a violation of the UN agreement. Time permitting, take a look at the Canada’s Charter of Rights and Freedoms (1982), which addresses mobility rights. While Canadians take mobility rights for granted today, the ability to travel across the country or move from one province to another freely was not one that was accorded to Japanese-Canadians, who were not able to return to Vancouver after the war—and worse, were given repatriation as one of the very few postwar options they had. If they did not move to Japan, they settled in other parts of Canada, where they continued to face discrimination and resentment.

Activity #3

Describe your reaction when you learned that the Canadian government sought the enlistment of Japanese-Canadians willing to serve in the Korean War? Or that there were 40 Japanese-Canadian exiles who joined?

Go Deeper

Serving in the Canadian Army was perceived as the only way back to Canada. Despite the losses, the confinement in internment camps, the displacement of families and the repatriation, there was still a desire and a need on the part of Japanese-Canadians to prove their loyalty, clear their names and return to Canada. This is not the only example where minority groups have served in the military in order to prove their worth as Canadians and earn their rights (see Chinese-Canadians during WWII).

Postscript

In 1988, Prime Minister Brian Mulroney formally apologized to Japanese-Canadian survivors and their families. Although no person was ever charged for treason or matters of national security, 22,000 Japanese-Canadians were displaced from their homes, separated from their families and confined to remote camps. In addition to an official government apology, $300 million in compensation was also paid.

Jse-Che Lam is a Toronto-based high school teacher who has taught English, history, politics, civics and various social science courses. Her interests include stories about migration, urban issues and all matters that concern Canadian produced film, literature and politics.

Pour lire cet article en français, cliquez ici.

Discover more Mini-Lessons | Watch educational films on NFB Education | Watch educational playlists on NFB Education | Follow NFB Education on Facebook | Follow NFB Education on Pinterest | Subscribe to the NFB Education Newsletter