Shannon Amen: Chris Dainty’s Animated Elegy

Shannon Amen: Chris Dainty’s Animated Elegy

June 12, 2006. Chris Dainty is visiting Guelph for a few days, celebrating his sister’s university graduation with family at a local restaurant, when his phone buzzes. He pulls it out and reads a message that haunts him to this day. “Chris…Oh My God. I think Shannon is dead.”

Time stands still… She’d been his close friend, his creative confidant, a daring tomboy unafraid to scale dangerous heights. They’d grown up in the same small town, attended the same church youth group, gone on road trips and made crazy art together. And now, barely into her twenties, Shannon Jamieson had taken her own life.

Dainty evokes the moment with sharp clarity in the newly completed Shannon Amen, richly textured animation in which he explores the nature of his own grief while crafting a luminous elegy to a gifted young queer artist who fought and lost the battle to reconcile her sexuality with her religious faith.

“Shannon laid out all the pieces”

The seeds for the project were planted years ago, during a casual conversation with Jamieson herself, just days before her death. “We were having breakfast at a restaurant in Hawkesbury,” Dainty remembers. “She’d slept over and we’d had fun, hot tubbing, chasing glow bugs and just hanging out. That morning in the restaurant, she was making me laugh, telling stories about a terrible job she had with a phone service. And at one point I said, I need to make a cartoon about you. She said, yeah that’d be great. Two days later she was gone.”

Dainty opens his film with a line of Jamieson’s poetry — My life is a fish story with an exaggerated plot. When you tell it, it’s funny. When I tell it, it’s not — and over 100 pieces of her artwork are woven into the fabric of his film, 15-minutes that fuse archival footage with 2D animation and Dainty’s own icemation. Whether it’s her darkly erotic paintings, her playfully revealing writing, or home video of Shannon giving spirited performances of her own songs in a deserted church, Jamieson’s presence and sensibility permeate the entire undertaking.

“She had laid out all the pieces,” says Dainty, who speaks of Jamieson as his co-director. “She created such a volume of work, I kept finding new things during the production. She was meticulous about documenting things, whole conversations we’d had on ICQ or MSM. I’d sometimes get lost in it all, but it was also revealing. Whenever I’d get stuck, I’d look through her stuff and find something new. She’d come and lead the way.”

The project quietly percolated in Dainty’s imagination for close to a decade before going into production. In the meantime Dainty would join forces with Jennifer Dainty, his life partner, to establish Dainty Productions, an Ottawa-based animation studio that’s developed expertise in a wide range of commercial animation, creating segments for Emmy award-winning TV shows like Odd Squad, Dino Dana and Dino Dan, and making interactive games for brands like Sesame Street and Hinterlands Who’s Who. Their clients include the Ottawa International Animation Festival, for whom Dainty has produced the festival sponsorship reel for 13 years running.

It was at the 2014 edition of OIAF that Dainty first proposed Shannon Amen to NFB producer Maral Mohammadian. “I wasn’t even planning to make a pitch,” recalls Dainty. “I’d got to know Maral through the festival and just felt this need to tell her the story. We ended up talking for hours, skipping a bunch of screenings. It was something she clearly connected with.” The project went into development in the NFB Animation Studio in 2016, with production kicking off in 2017.

“That barn was like church”

Imagery generated from a seemingly carefree photo shoot that Dainty and Jamieson did together in 2004 occupies a central place. “She was going to Lyon, France, to work on an art project, an idea that involved stained glass and a hanging rope,” says Dainty. “She wanted some reference photos, and I said, cool, let’s go do it, and on the way there, I suggested we pick up another friend, one of her on-and-off girlfriends.”

The location was a vast farmer’s barn in the Ottawa Valley, and as it turns out, it would be the place where Shannon died by suicide two years later. “When I think back, of course I wonder about that dark imagery, the hanging rope. But I didn’t even think to ask about it at the time. We were just having fun. At one point Shannon took off her clothes. We were comfortable with each other. We were making art.”

Dainty would take a series of radiant photographs of Shannon cavorting with her girlfriend, some of which now appear in Shannon Amen. “The light was pouring into the barn. It was beautiful. To Shannon, it was like a church. A place of reverence.”

“Shannon was attached to her faith.”

Dainty’s photos from that shoot would provide Jamieson with raw material for a project she called War, in which she wrangled with the conflict between her faith and sexual identity. When she exhibited the work at the National Queer Arts Festival in San Francisco in 2005, her artist’s statement stated: “As a queer ex-Christian, I abandoned ship because of the churches’ restrictive gender and sexuality politics. Filled with a learned fear and shame for my desires, I am determined to unlearn messages that only led to self-disgust. I am at WAR with the establishment that taught me that God’s light did not shine on queers.”

It was a battle that would eventually defeat her. “Shannon was attached to her faith,” says Dainty, who was also raised in a Christian household, attending many of the same church events as Shannon did. “At one point she confided in a minister about being gay. He told her she didn’t have to be that way, and then went on to tell other people about their private conversation. It was such a breach of trust. I still see many wonderful things in Christianity but it’s terrible to do that, to make someone decide between being Christian or gay. Shannon had embraced her sexuality but she had this terrible internal struggle. I hope people will watch this film and give thought to what that feels like, to be excluded from a community that you’ve been part of all your life.”

The fight for LGBTQ rights is far from over, Dainty points out. “I recently had a conversation where someone was questioning the need for pride events. ‘They have equal rights now, don’t they?’ That was the argument, and it’s true that, here in Canada, we have made some progress. But there’s so much more that needs to be said and done. And there are around 70 countries where it is still illegal to even be gay, so I’m really hoping that this film can reach a world audience. Society needs to accelerate acceptance to save lives.”

The Icemation Age

As a longtime member and former vice president of the Canadian Ice Carvers Society, Dainty creates large-scale ice sculptures for Ottawa’s annual Winterlude Festival, and in recent years he’s been experimenting with ways to bring ice into the world of animated film.

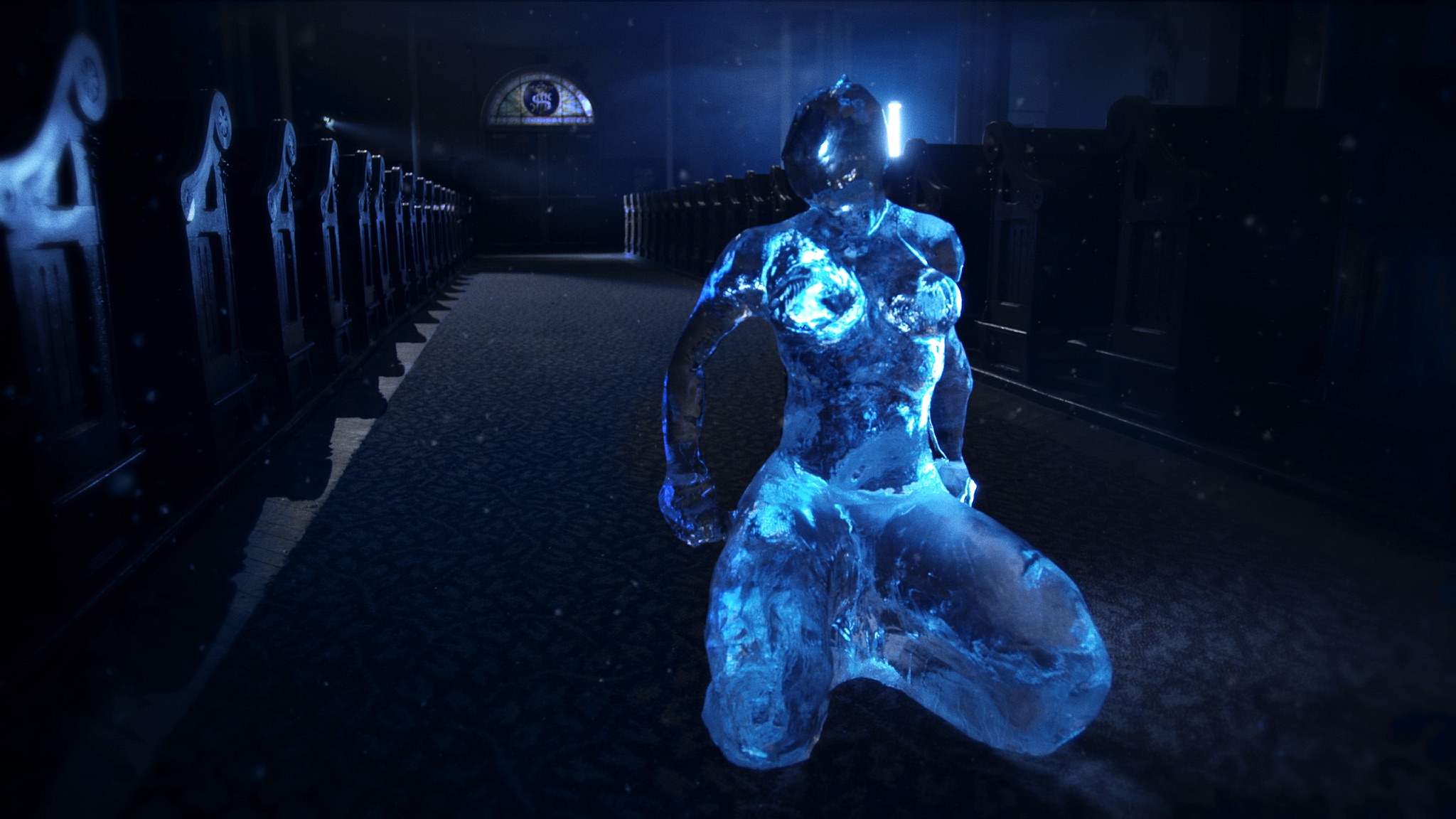

With Shannon Amen he combines 2D animation with a technique of his own invention that he’s dubbed ‘icemation,’ using stop motion and puppetry to animate large-scale human figures and objects carved in ice. It’s an aesthetic, he feels, that’s particularly suited to Shannon’s story. “She was a strong individual yet had a fragile side, one that she kept hidden, and ice has so many different reflections, depending how you look at it. It’s strong but if treated the wrong way it will also shatter.”

Using equipment located on the premises of the Ice Carvers Society, Dainty and his team harvested large blocks of crystal clear ice, transporting them to a freezer room where they employed chainsaws to sculpt life-size figures, using hand chisels to add finer detail. The sculptures were then transported via freezer truck to Ottawa’s St. Brigid’s Church, where the icemation sequences were filmed. “It was pretty challenging. We had some sculptures break along the way. They were extremely heavy too — around 300 pounds per sculpture — but I loved the fact that we were animating with an element of nature,” says Dainty.

Trevor Dixon Bennett, Dainty’s editor on Shannon Amen, made this short video about the icemation process:

Blood, sweat & tears: NFB Influences

In calling his technique icemation, Dainty was inspired by the late NFB director Grant Munro, who’s credited with coining the term pixilation to describe the novel technique Norman McLaren used in the classic short Neighbours. “I didn’t get to show Grant this film before he passed, unfortunately,” says Dainty, “but I did ask him if he had any advice for me as an NFB director. ‘F**k computers!’ is what he told me. I said, ‘well I’m using blocks of ice and chainsaws, so I should be good!”

“It’s always been on my bucket list to work with the NFB,” says Dainty. “I’ve been making mostly commercial animation until now, but I’ve been going to the Ottawa Animation Festival every year since 1995. I’ve seen great work from the NFB. It has such variety, and that’s what really inspires me, how different the films are from each other.”

Among the NFB films he cites as direct influences is Blood Manifesto in which Theodore Ushev animated drawings made with his own blood. “Shannon had created art that incorporated drops and splatters of her own blood, some of which we used in the film. Those images and Ushev’s film were my inspiration to animate my own blood overtop a scene of the church is exploding.”

Team of all-star animators

Dainty’s team included Lynn Scatcherd who animated traditionally on paper, and David Seitz who produced digital hand-drawn animation for the film’s climax. Rounding out his team were Phil Lockerby, Hyun Jin Park, Andrew Doris, Luc Chamberland, Sean Branigan, Rodolphe Saint-Gelais, and Dainty himself. Each frame of character animation was then coloured by Izzy Campbell. “Izzy also acted as a Shannon stand-in for a few scenes in the film,” says Dainty. “We needed reference footage for the scene after the pride parade, and Izzy was able to bring her own experience as a young queer woman to that sequence, making it really powerful.”

“Shannon’s artwork was the driving force for the entire film,” says Dainty, “Elise Simard did great work with post-colour texturing, working with high-resolution scans of Shannon’s artworks and applying the textures digitally onto the characters, and Jennifer Dainty referenced Shannon’s style to hand-paint the crows throughout the film. It was amazing to see it all come together. It was all touched by Shannon in some way.”

Sound designer Sacha Ratcliffe worked with original compositions by Shannon, along with compositions by Shannon’s friend Brett Despotovich, mixing them with her own atmospheric tones and violin phrasing by Lyndell Montgomery. “Lyndell’s work was added at the eleventh hour,” says Dainty. “We were doing colour grading and final mix, but I had this gut feeling that the sound was missing something. We were so close to wrapping: Maral said I was nuts. But I trusted my instincts. My direction to Lyndell was, just watch the film and improvise, let your emotions be your guide. Her violin brought a new intensity to the soundtrack. Lyndell was the last person to see Shannon alive. They were friends, and Shannon really looked up to Lyndell as a positive lesbian role model, living opposite her grandmother’s farm. She loved Lyndell’s music. I think she would love the fact that her friends are involved.”

“Jennifer (Dainty) who was the line producer, and Maral were absolutely key,” he says. “They both gave their all. It was easy to get off track on this project, with the amount of content that Shannon left behind, but Jennifer and Maral kept me on track. They made a huge creative contribution, whether it was developing the story or changing new visual elements. The whole process has been very collaborative, and I had some really talented people working with me. Their talents brought it to the next level.”

Carving the human form in ice

Dainty enlisted a small crew of seasoned ice carvers to help with the icemation segments. “They were another key force in the production. I had worked with Kevin Ashe in 2015, at the International Winterlude Competition, where we carved a tree comprised of human bodies. The human form is one of the most challenging things to carve in ice. It’s not for the faint-hearted, but that experience gave me confidence that we could create something on an epic scale, with full-scale human sculptures. Kevin really helped define the look we were going for.”

Also on ice carving duty was Iraqi-Canadian artist Mowafak Nema. “Mowafak was able capture something of Shannon’s essence in ice,” says Dainty, “ especially in the scenes based on the photo of Shannon in the barn. My friends in the Canadian Ice Carvers Society worked really hard to make this project possible.”

“Art is therapy”

“I feel like I’ve grown with this film, artistically and in all kinds of other ways,” says Dainty. “It’s brought me closer to Shannon. I’m finally at peace with what happened. Art is therapy, I believe that, and something has lifted from my shoulders. There have been so many highs and lows during this production. It was hard, emotionally draining, and there were days when I didn’t want to get out of bed. But that chapter has come to an end.”

“When I think of the journey that took me from that conversation with Shannon, all those years ago, when we talked about making a cartoon together, to finishing this film, it’s just the best feeling. Yes, it’s been hard — blood, sweat and tears, literally — but it has paid off and I’m really proud of the results.”

Shannon Amen is written and directed by Chris Dainty. It was line produced by Jennifer Dainty, produced by Maral Mohammadian and executive produced by Michael Fukushima at the NFB Animation Studio. It is scheduled for release in fall 2019.