Our Dominion Over All Other Creatures | Curator’s Perspective

Our Dominion Over All Other Creatures | Curator’s Perspective

Fifty years ago, the NFB was commissioned by the Canadian Wildlife Service (CWS) to make a film about the work of its specialists in the preservation of Canada’s various animals and habitats.

The resulting film, Atonement, directed by Michael McKennirey, was praised around the world for its portrait of these dedicated people and for its positive message. I thought I would take a look back at this forgotten film and talk about some of the lessons it taught us.

This might surprise contemporary environmentalists, but in the late 1960s and early 1970s there was a great deal of talk in North America about preserving wildlife. Nature documentaries were released in cinemas regularly and many nature shows were aired on television. (In Canada, The Nature of Things has been broadcast on the CBC since 1960.) There was an awakening of people to the dangers our wildlife were facing. Unfortunately, the media focused more on the failures than anything else, but there were a few positive voices, nonetheless.

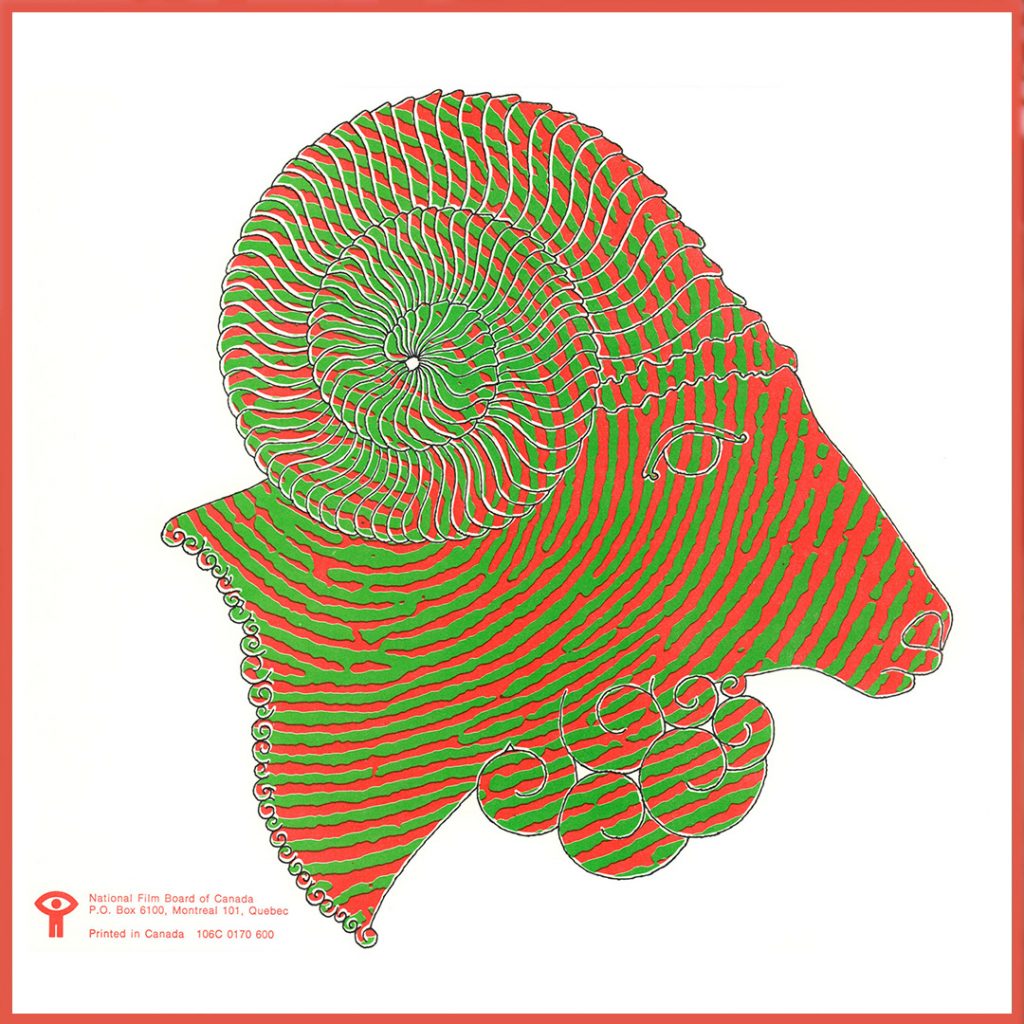

(Here is beautiful artwork from the Atonement poster)

The NFB had been making nature films since the 1940s, although most of them focused on how to preserve nature for the benefit of our economic wealth. In the 1960s, this began to change when filmmakers started to make films that spoke to the importance of preserving animals and habitats (The Enduring Wilderness, from 1963, is an excellent example of this type of film).

Atonement was the continuation of a collaboration between the NFB and the Canadian Wildlife Service. Together they had created the Hinterland Who’s Who series of short PSAs that continued into the late 1970s.

The film starts with specialists vaccinating bison against anthrax at Wood Buffalo National Park. It’s explained that there were once 10 million bison in North America; by the end of the 19th century, the species was almost completely annihilated by hunters. Thanks to the work of the CWS, the population was bumped up to 12,000 in 1970 (today, bison number more than 31,000).

As we see in the film, vaccinating animals is just a small part of the CWS’s duties. They breed fish in ideal conditions and test lakes to see if the water can sustain the released fish. They look at the effects of pesticides on falcons and other birds. The CWS also blast giant craters in New Brunswick marshes that eventually get filled with water, where vegetation can grow. A perfect way to help duck populations increase in size.

Atonement tells us of the fate of the whooping crane, whose numbers dwindled to a paltry 14 in 1941! They were not hunted but rather died out—crowded out by farmers who encroached on their habitat. The film points out that the crane was never an abundant species, but the CWS managed to get numbers up to 56 by 1970 (there are over 800 today). Cranes will often lay two eggs, but it’s extremely rare for both eggs to hatch. As cranes are migratory birds, officers of the CWS would take one of the eggs before it hatched and fly it to Texas by military jet so that it could be raised in captivity before being released into the wild. This was a highly successful program.

The film then moves on to grizzly bears. Did you know that they once lived as far south as Mexico? The bears were hunted into extinction there by farmers trying to protect their cattle. When Atonement was made, the CWS were in the last phase of a five-year study on the population dynamics of the grizzly. They were trying to make sure Canadian grizzlies didn’t share the fate of their Mexican cousins. Using such techniques as installing radio collars on the bears, they hoped to be able to see just how far their natural habitat extended.

Lastly, the CWS also set up wildlife centres to help children form a relationship with nature, as they are the future guardians of wildlife.

Atonement, Michael McKennirey, provided by the National Film Board of Canada

Atonement was broadcast on the full CBC network on September 12, 1971, to ecstatic reviews. The Calgary Herald called it “(a) fascinating and dramatic story.” A French version entitled Compte à rebours was broadcast on Radio-Canada, on June 25, 1972, to positive reviews. The film was versioned into Dutch, Hindi, German, Spanish and Japanese as well, and sold around the world. It won several awards, including one for Michael McKennirey at the Canadian Film Awards in the non-feature craft category. A 20-minute version was also produced, under the title Keepers of Wildlife, for use in classrooms.

I was struck by many things upon re-watching this film. Firstly, the work of these wonderful people is simply inspiring. Secondly, regardless of humanity’s past failures, the message of the film remains a positive one. Thirdly, preservation of our wildlife has been going on for a lot longer than people think: the CWS was established in 1947 but had its roots in the Migratory Birds Convention Act of 1917.

I invite you to watch this beautiful film that shows that, although we have dominion over all other creatures, it is up to us to use this power wisely.

Enjoy the film.

Thanks for this blog post, Mr. Ohayon. I had no idea that Grizzlies had once been down so far south. I will be rewatching this gem for sure!.