Higher Learning | RUMBLE: The Indians Who Rocked the World

Higher Learning | RUMBLE: The Indians Who Rocked the World

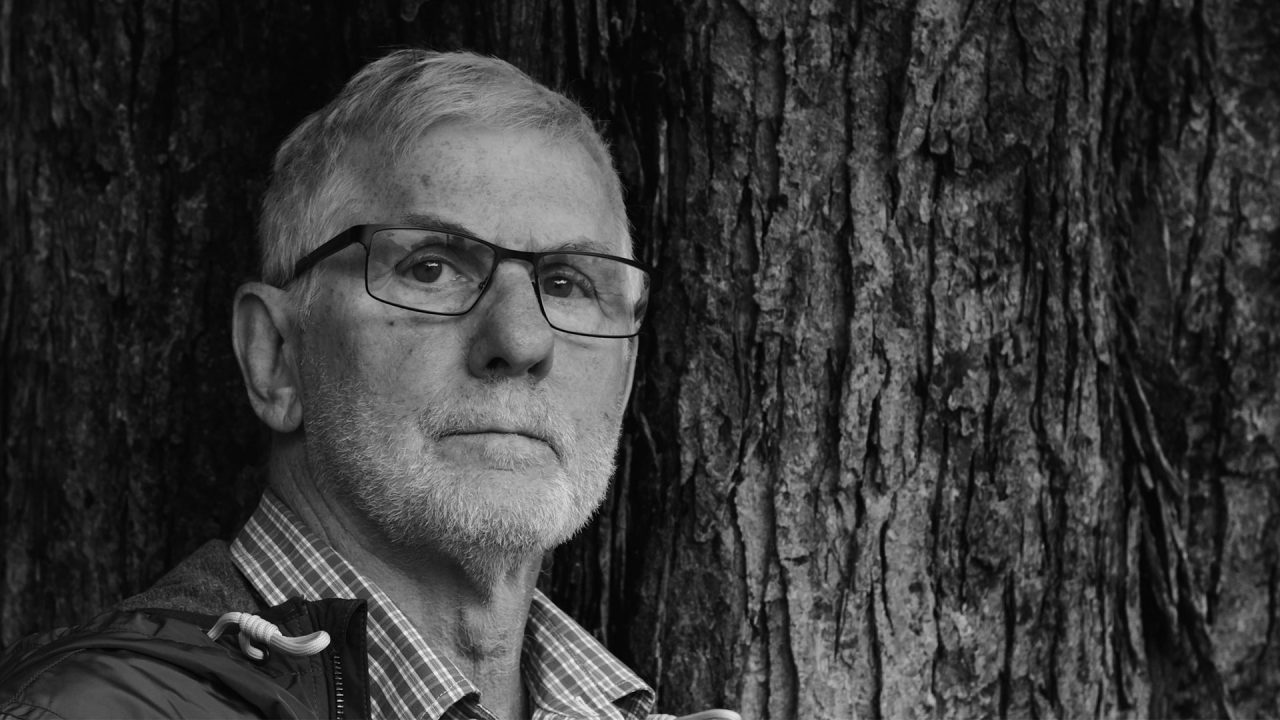

Above Photo: Link Wray, 1970s by Bruce Steinberg. Courtesy of linkwray.com.

Rumble: Challenging Indigenous Erasure through Active Presencing

The film Rumble: The Indians Who Rocked the World highlights Indigenous contributions to North American popular music, including (but not limited to) rhythm and blues, jazz and rock ‘n’ roll. In so doing, the documentary demonstrates how the development of some popular genres is due in part to the talent and efforts of Indigenous Peoples. Additionally, Rumble illustrates how Indigenous musics of various nations may be the antecedent of many popular genres as we know and hear them.

RUMBLE: The Indians Who Rocked the World, Catherine Bainbridge, provided by the National Film Board of Canada

In connecting Indigenous musicians’ influence on non-Indigenous artists across generations and genres, Rumble emphasizes how Indigenous cultures and Peoples have deeply affected the music we regularly consume. One example is Charley Patton’s far-reaching influence on non-Indigenous musicians such as Eric Clapton, Bob Dylan, Bonnie Raitt and Jack White. While Patton is largely considered to be the “grandfather” of the blues, his impact on country music and rock ‘n’ roll is still being heard. Mildred Bailey’s impact on jazz vocalists such as Bing Crosby, Frank Sinatra, Tony Bennett, Ella Fitzgerald and Billie Holiday offers another example. The intersections between Indigenous and non-Indigenous musicians explored in the film exemplify how specific sounds and styles are attributed to commercially successful musicians rather than to the Indigenous Peoples who birthed these rhythms and melodies.

In this way, the documentary speaks to the erasure of Indigenous Peoples and the ways in which they are repeatedly silenced and removed from conversations about music and popular culture. More broadly, this film also points to the colonial erasure of Indigenous life. Much of this is evidenced through interviews with Indigenous musicians such as Buffy Sainte-Marie. Her candid account of how her music was supressed by the American government and institutions such as the FBI and the CIA illustrates one aspect of Indigenous erasure while foregrounding Indigenous responses to colonial prejudices and institutional wrongdoings.

In my own work with Inuit throat singers and hip hoppers, I’ve learned about the various ways Indigenous Peoples have continuously adjusted to the world around them. From colonial control over Indigenous lands and cultures, to government-funded assimilative practices, Indigenous Peoples have adapted to the external circumstances imposed on them. However, colonial domination does not remove Indigenous presence, nor does it eliminate Indigenous cultures and arts practices like music.

It is within this space that Rumble shines. By exploring how Indigenous cultures and peoples affect(ed) North American popular music making, Rumble makes an important contribution to the acknowledgment of Indigenous presence and how the aural legacies of Indigenous musicians are still knowingly/unknowingly being heard. These aural legacies include drummer Randy Castillo and guitarist Stevie Salas. Their collaborations with Ozzy Osbourne and Rod Stewart, respectively, demonstrate how Indigenous musicians remain largely unknown for their contributions to some of the most popular and commercially successful songs and albums. By highlighting these musicians, Rumble creates a pathway to hearing and learning more about these legacies.

The film’s exploration of Redbone’s “Come and Get Your Love” created a pathway for me. Originally released in 1974, “Come and Get Your Love” was a commercial success, and Redbone became the first Indigenous band to break the Billboard Hot 100 chart. The song saw a resurgence when Marvel Studios featured it in Guardians of the Galaxy (2014) and Avengers: Endgame (2019). It was re-popularized further on TikTok, Netflix (F is for Family) and Hulu (Reservation Dogs), and while I had heard it many times prior, I didn’t know Redbone was an Indigenous group until I saw Rumble.

The inclusion of a short clip of Redbone performing live on Burt Sugarman’s The Midnight Special prompted me to look for the full video on YouTube. Redbone’s performance demonstrates how traditional Indigenous music and dance co-exist(ed) with contemporary genres. Moreover, the film’s exploration of Redbone’s performance, in addition to a discussion of how the Black Eyed Peas were influenced by “Come and Get Your Love,” subtly speaks back to, and challenges, Indigenous erasure through the active presencing of Indigenous Peoples, while emboldening their aural legacies.

So, my (re)learning of “Come and Get Your Love,” as well as my (re)discovery of other Indigenous musicians and songs, demonstrate that the music I’ve heard and recognized as the sounds that define North American popular music is in fact comprised of sounds that define North American Indigenous music.

The musicians I grew up listening to, such as Guns N’ Roses, Metallica and the Ramones, were heavily influenced by Indigenous musicians like Link Wray and Jimi Hendrix. As these influences cut across generations and genres, the aural legacies of Indigenous musicians begin to deconstruct their erasure. Accordingly, films like Rumble become increasingly important as they are a musical reminder that Indigenous Peoples have always been here; they have always been present, and their contributions to the music that shapes our lives deserve to be heard and respected. Their voices, stories and experiences must be heard.

Raj Singh, Ph.D., is a postdoctoral scholar in the Don Wright Faculty of Music at Western University. Her research interests include Critical Indigenous Theory, Indigenous methodologies and Indigenous modernities. Her work with Inuit musicians explores how Inuit combine contemporary genres of music with traditional practices such as katajjaq to include new realms of lived experiences. Her current work with Inuit hip hoppers interrogates gender, identity, and belonging at its intersection with decolonization, intergenerational trauma, cultural health, and wellbeing.

Pour lire cet article en français, cliquez ici.

Discover more Educational blog posts | Watch educational films on NFB Education | Watch educational playlists on NFB Education | Follow NFB Education on Facebook | Follow NFB Education on Pinterest | Subscribe to the NFB Education Newsletter