Higher Learning | Waiting for Raif

Higher Learning | Waiting for Raif

Waiting for Raif: an engagé documentary about the wife of imprisoned Saudi blogger Raif Badawi

Keywords: Human rights, prisoner of conscience, Raif, Saudi Arabia

Waiting for Raif, Luc Côté & Patricio Henríquez, provided by the National Film Board of Canada

The perfect title

The title of this feature-length documentary by Patricio Henriquez and Luc Côté is particularly well chosen. Waiting for Raif tells the story of jailed Saudi blogger Raif Badawi—now famous in Quebec and the rest of Canada—but mostly the story of his wife, Ensaf Haidar, their three children and their lives in Sherbrooke, Quebec, where the family sought refuge while “waiting for Raif.”

Socially engaged filmmakers

When the blogger began serving his 10-year prison sentence for “insulting Islam”—and living in fear that the additional punishment, 1,000 lashes, would be enforced—directors Patricio Henriquez and Luc Côté embarked on a filmmaking odyssey that was to last eight years. They shot several hundred hours of footage, which they eventually condensed into a runtime of a little over two hours.

The pair were no newcomers to engagé filmmaking, having previously made You Don’t Like the Truth: 4 Days Inside Guantánamo, about Omar Khadr. And Henriquez is well acquainted with dictatorial regimes, having himself fled Pinochet’s Chile in 1974, settling in Quebec. How can media and art play key roles in defending human rights and raising awareness of global issues?

Ensaf’s struggle

The filmmakers follow Ensaf Haidar as she adapts to a new life in Quebec, wages a battle to raise awareness of Raif’s plight and, she hopes, secure his early release, and in the process becomes a public figure. Henriquez and Côté intimately record the family’s daily life in Sherbrooke, the children’s first days at school and Ensaf’s travels abroad to lobby on behalf of Raif, who receives human rights awards in absentia.

The documentary takes the family’s side but eschews complacency; the directors don’t shy away from occasionally depicting situations that are somewhat sensitive, like Ensaf’s time as a candidate for the Bloc Québécois in the 2021 federal election and her faltering attempt to read a speech in French.

Ensaf’s transformation

Ensaf Haidar’s metamorphosis from “wife of prisoner Raif Badawi” to activist and defender of human rights is one of the main thrusts of the feature documentary. The young mother sometimes seems overwhelmed by events early on but gains confidence as time goes by, her character becoming central to Waiting for Raif. This prompts us to reflect on how Ensaf’s transformation, from prisoner’s wife to activist, exemplifies the motivating forces that can lead people to take an active stand in favour of human rights.

The children’s eloquence

Before long, there is a groundswell of community support, with people supporting Ensaf and her dedication to the cause of freeing her husband. The Badawi children (two girls, Najwa and Miriyam, and a boy, Tirad, known as Doudi) grow up during the making of Waiting for Raif and become eloquent advocates for the right to be reunited with their father and hug him once more. A sequence showing their interview with TV host André Robitaille is especially moving.

Saudi power

While chronicling the family’s story, the filmmakers examine the unique geopolitical context shaping Canada’s relations with Saudi Arabia. Men and women in Canada’s parliament take selfies with Ensaf and the children one day and approve record sales of armoured vehicles to the Saudi regime the next. The timeline of the story spans the Harper and Trudeau governments, both of which, despite their clear ideological differences, support sales of military equipment to the Saudi kingdom, even while being at war with Yemen.

Could Canadian authorities have done more for Raif Badawi? Must fundamental human rights like freedom of expression be viewed as secondary to maintaining defence contracts and jobs at Canadian firms that export to Saudi Arabia? Can economic and business interests be reconciled with ethical values and human rights? What is the responsibility of government in such situations? These are some of the many issues raised by this documentary.

An engaged community

Another facet of the Badawi affair that’s explored in Waiting for Raif is the dedication of the Sherbrooke community and human rights organizations, notably Amnesty International, to the struggle for Raif’s liberation. That the prisoner’s supporters steadfastly maintained an outdoor vigil in front of Sherbrooke’s city hall every Friday for eight years, regardless of the weather, seems hard to believe, but it really happened.

Some say that we live in a society of the ephemeral, in which the average adult’s attention span is no more than 30 minutes. How does that sustained support from the Sherbrooke community challenge the stereotype of modern society preferring short-lived and superficial attention? What does it teach us about society’s capacity for perseverance and mobilization? The continuous engagement of filmmakers Henriquez and Côté over a span of eight years is no less remarkable, since they had no idea how long the story would last when they began chronicling it.

In view of the many questions it raises, and its dramatic and political power, Waiting for Raif is well worth showing in institutions of higher learning.

What happens next?

As the film unfolds, we begin to hope that this story will not be a repeat of Waiting for Godot. As viewers, we go through the same gamut of emotions as Ensaf, Najwa, Doudi and Miriyam. What does the future hold for the Badawi family? Will there be a sequel to Waiting for Raif and, if yes, what would its title be? For now, no one knows the answers to these questions.

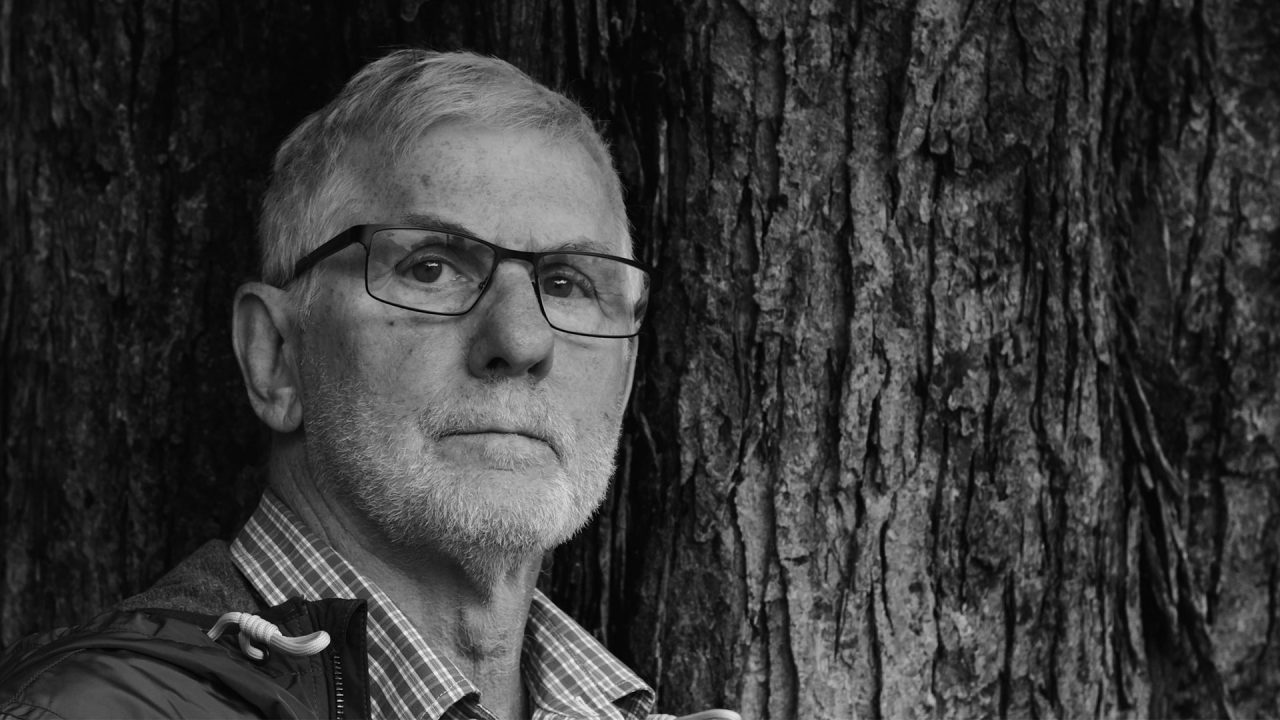

Gilles Sabourin has been an active member of Amnesty International for more than 40 years and was vice-chair of the organization’s Canadian Francophone Branch during Raif Badawi’s imprisonment. A retired engineer and science communicator, he is the author of the book Montreal and the Bomb (2021), the original French version of which won Quebec’s Hubert Reeves award for popular science writing. An impassioned cinephile, he started the Ciné-Club Outrepont, a film society in Saint-Lambert, with his wife in February 2023.

Pour lire cet article en français, cliquez ici.

Discover more Educational blog posts | Watch educational films on NFB Education | Watch educational playlists on NFB Education | Follow NFB Education on Facebook | Follow NFB Education on Pinterest | Subscribe to the NFB Education Newsletter