Ink has a life of its own, says inkmaker for Robert Crumb, Margaret Atwood

Ink has a life of its own, says inkmaker for Robert Crumb, Margaret Atwood

I’ve been making my own ink for almost 10 years now as the founder of the Toronto Ink Company. This urban-foraged ink company began in my kitchen with an ingredient that literally fell from a tree. It was a black walnut. Black walnuts look a bit like limes and can be found on the ground in the autumn, at the base of a tree that’s common throughout North America and Europe. I knew that black walnuts could be made into ink because of a small bottle of the stuff that I’d bought years before, when I was living in New York, working as an illustrator.

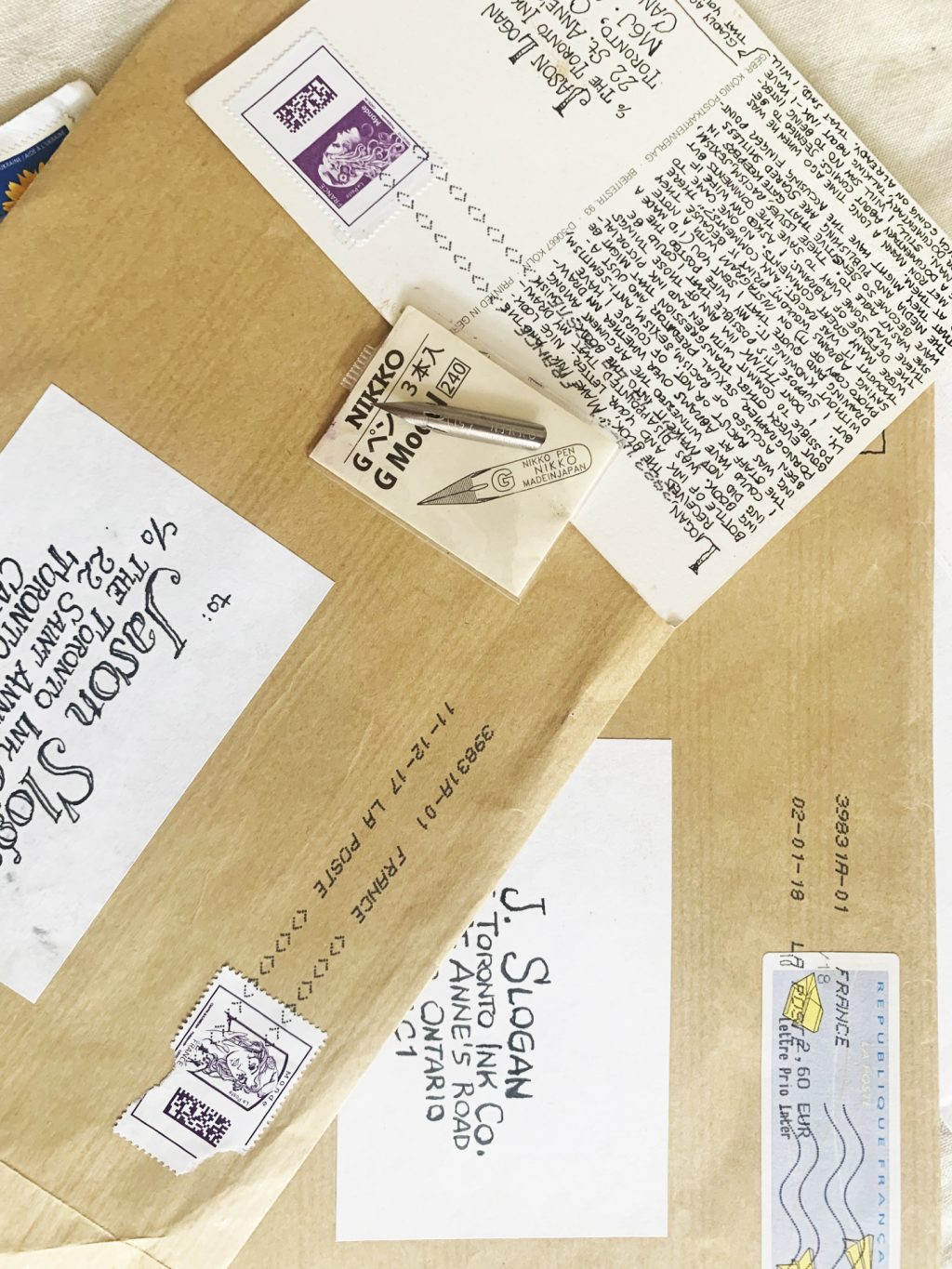

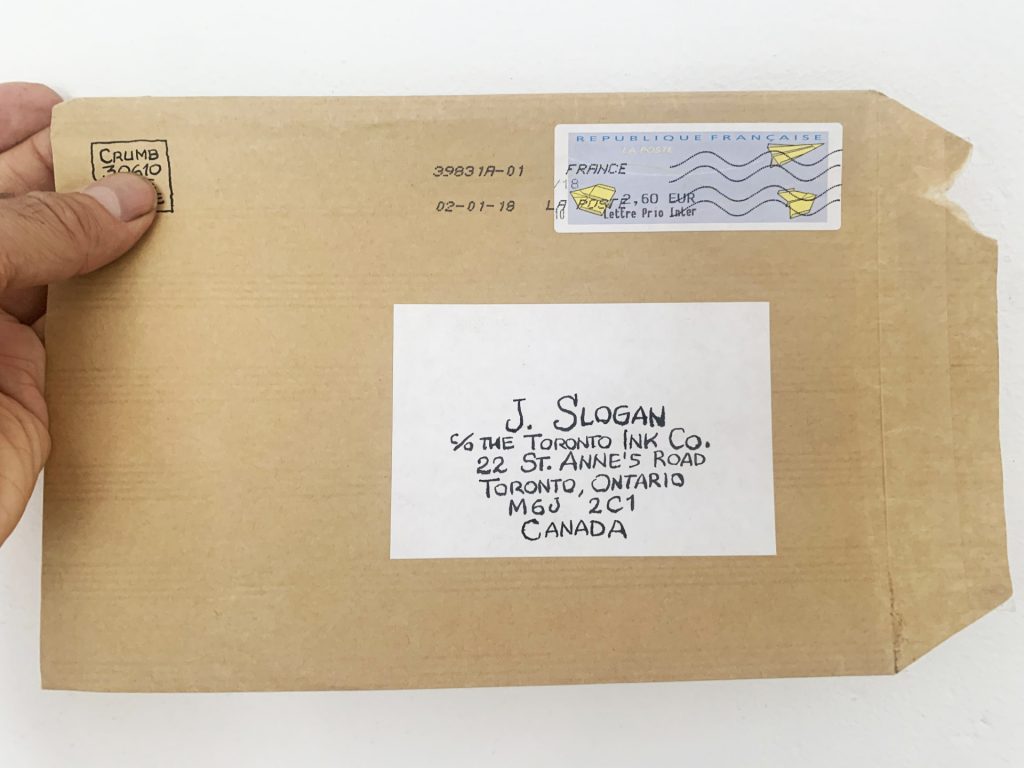

Back in Toronto, I foraged a backpack full of black walnuts in a park on my way to work and boiled up just the outer green hulls in a big pot of water for a few hours. I strained the results into a really beautiful mahogany-coloured ink, which I bottled, packaged and mailed out all over the world to illustrators, artists and calligraphers whom I’d met over the years as early beta testers.

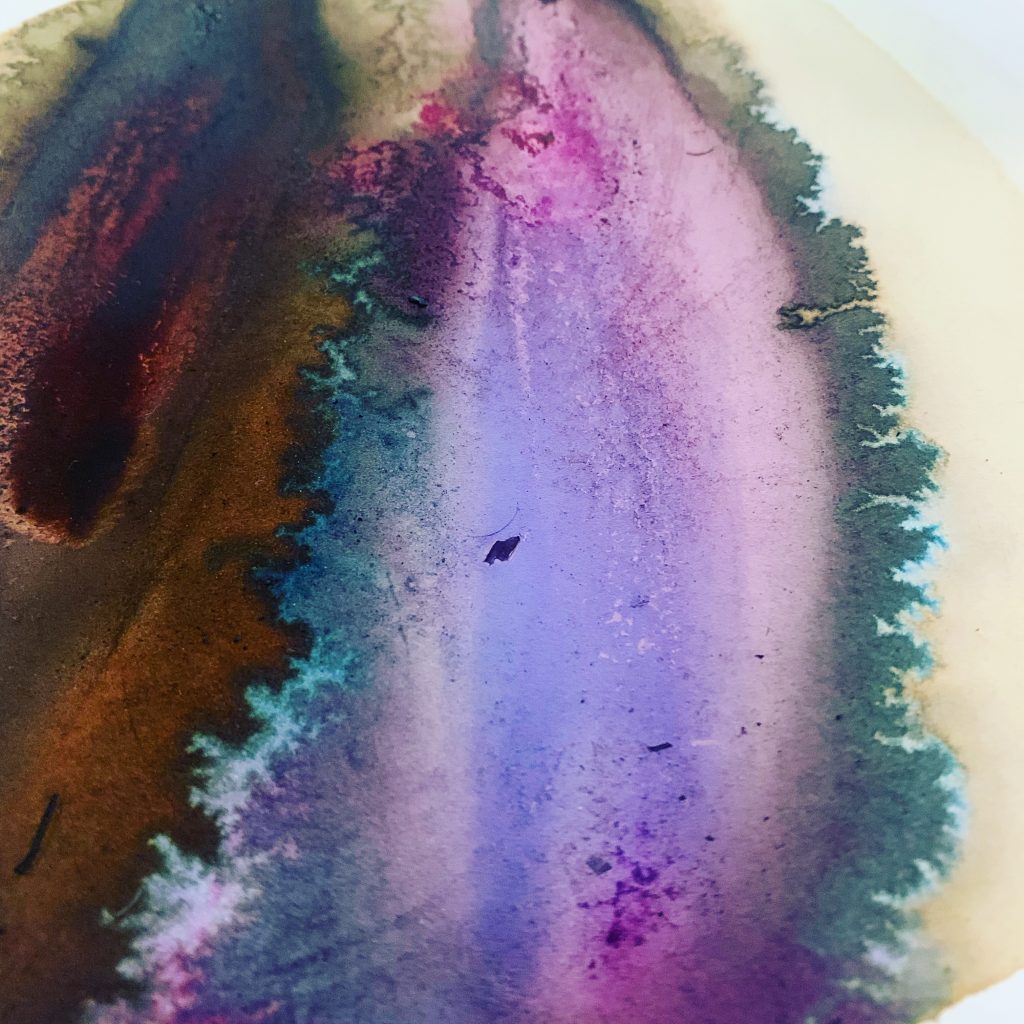

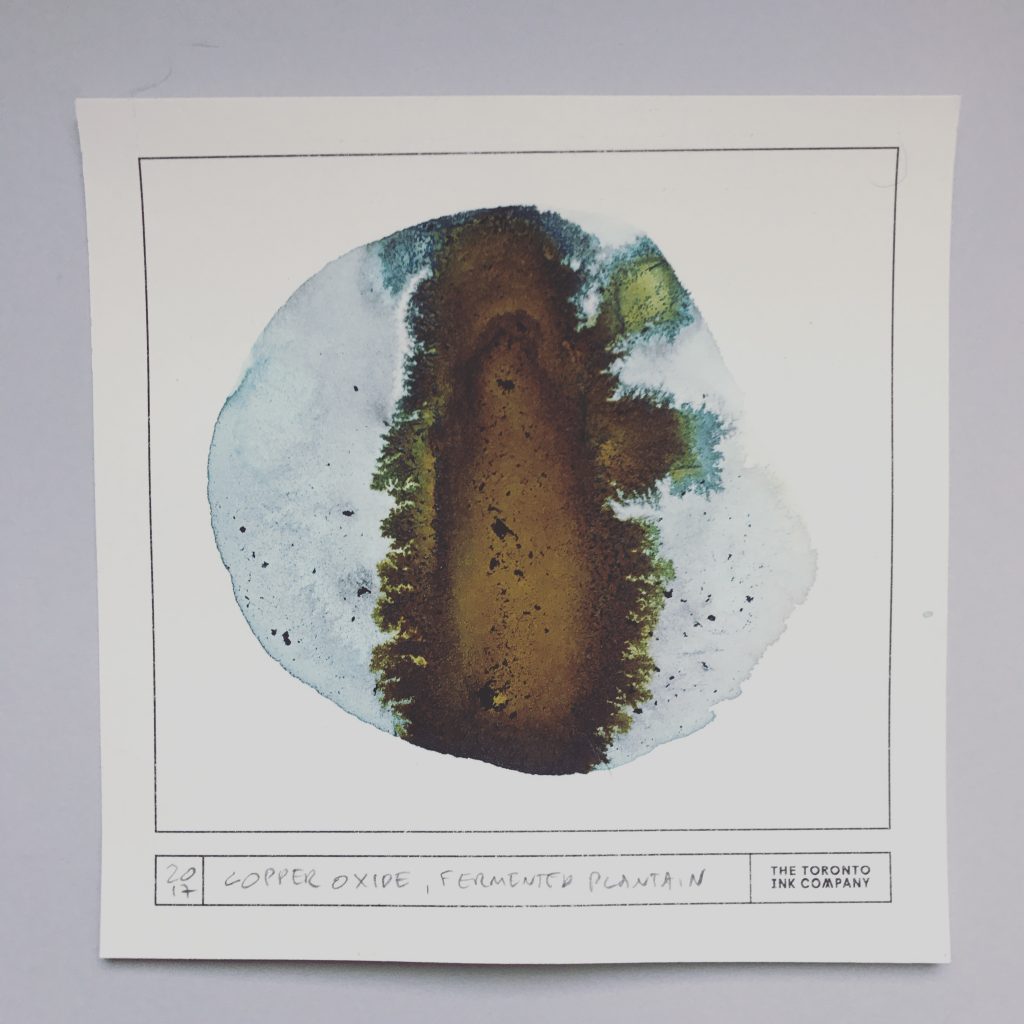

I branched out as a small-batch inkmaker into turmeric, wild grape, sumac and all kinds of other natural pigment materials I foraged from the streets. I love harvesting and experimenting with berries, leaves, roots, nuts and other overlooked sources of urban colour and making them into colourful, non-toxic inks for brush and dip pens.

Right from the beginning I sold my inks as living colours. Part of the charm of natural inks is their unpredictable nature. They can change hue, darken, lighten, crystalize and affect each other in all kinds of surprising ways. Similarly, each bottle of ink that I make expresses a particular terroir: the “when and where,” “how” and sometimes even “why” of its ingredients. I have found a real virtue in this ephemeral quality of natural inks, and the artists that I make ink for generally appreciate the element of surprise they embody.

It’s a theme that plays out in The Colour of Ink, whereyou get to see some incredible artists and illustrators experimenting with these inks and meet a whole range of natural colour experts and explorers from around the world. From a cochineal farmer in Oaxaca to a Japanese calligrapher making wall-sized single characters and a totem pole carver in the Haida Gwaii archipelago in British Columbia, we see hand-made colour coming to life in all kinds of traditional and futuristics ways. Ink is alive.

The Colour of Ink, Brian D. Johnson, provided by the National Film Board of Canada

But while many artists appreciate ephemeral, unpredictable inks, I have to say that the question I get asked more than any other is: How long does this ink last? For fountain-pen enthusiasts, calligraphers, professional artists, mapmakers and anyone concerned with archiving, the idea of an ink that might fade away or behave in unexpected ways is a bit unnerving.

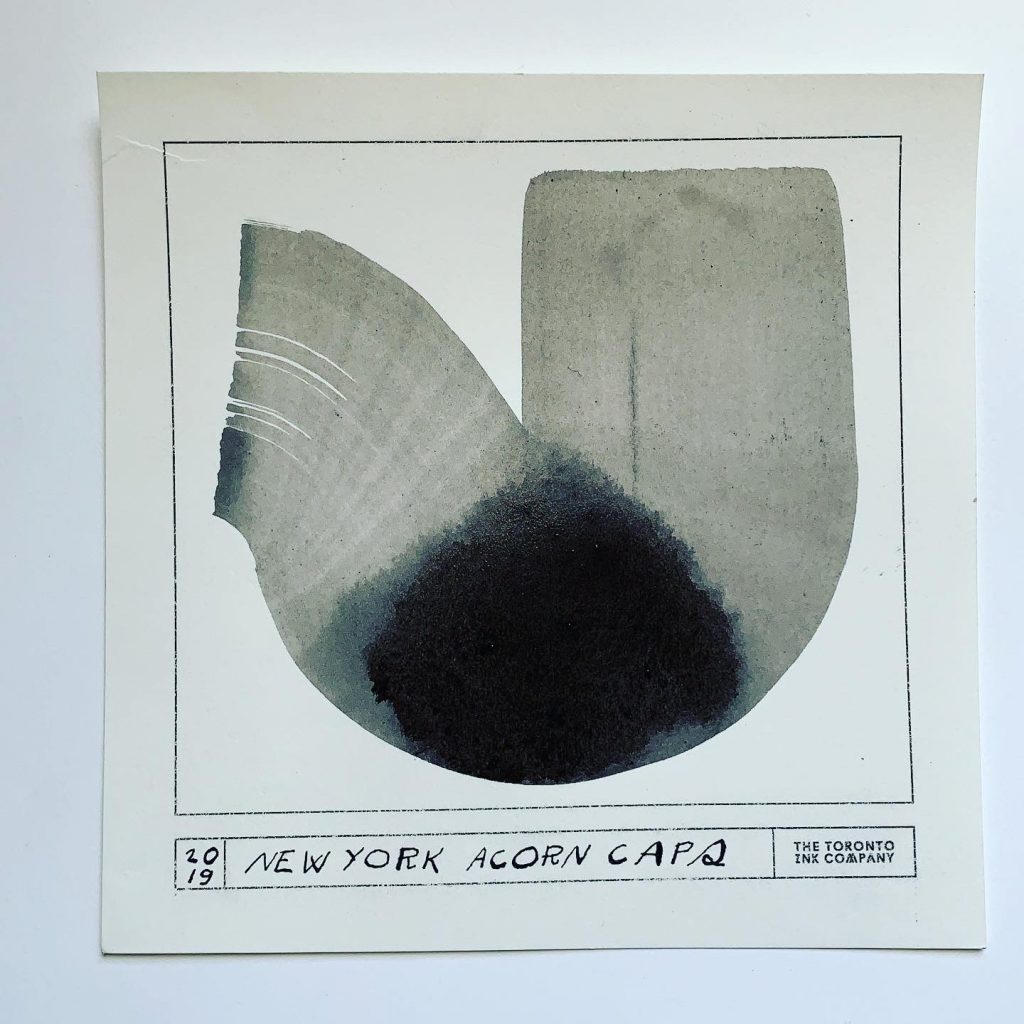

I have two responses to this. First: if you’re looking for an archival, stable, UV-proof ink that works the same every time, there are thousands of chemical options at your stationery or art supply store. My second answer, especially if you like black, is carbon ink. Carbon-based ink is totally natural and non-toxic and has been glistening beautifully and agelessly on parchment, papyrus and paper scrolls for a few thousand years. The very first inks of Egypt and China were carbon inks made from either charred wood, vine or bone, or soot from burning oil. Mix this carbon with water and a binder like fish glue or tree sap and you get an ink that’s perfect for making letterforms and linework that last forever. And while it’s true that carbon ink can be rubbed away, it doesn’t fade.

My personal favourite of the carbon inks is called Lamp Black. It’s a traditional recipe made by collecting the fine particles of soot that form on the inside of the glass of an old-fashioned hurricane lamp and mixing this fine dust with gum arabic and water. It’s a bit time consuming. Okay, quite time consuming, but because the soot is so fine, the resulting ink is silky smooth and jet black. It makes a fine, consistent, easy-flowing pen ink that I make for preferred customers like Robert Crumb and Kōji Kakinuma. When you use a carbon-based ink, you are using a material that shares the same chemistry as all plants and animals on Earth. When you make marks with a pen or marker, or brush with carbon black ink, you’re sharing a tradition that goes back to the beginning of the written record—and a method of memorializing that has the potential to be around for thousands of years after the pixels of cloud computing have fizzled out.

I’ve always loved this dual nature of ink. It’s a liquid that can form fine, crisp, contrasty lines aimed at bold, lasting unambiguous images and letterforms; but add a little water, and ink starts moving and changing, taking on a dreamy, mysterious life of its own as it moves across paper.

The Colour of Ink (which no inktoberist should miss) explores these two sides of ink. Both the dark line that lasts forever and the colour-filled wash that lives in the moment.