Carlos Ferrand’s Cimarrones and the Peruvian New Wave at the NFB | Curator’s Perspective

Carlos Ferrand’s Cimarrones and the Peruvian New Wave at the NFB | Curator’s Perspective

To mark Latin American Heritage Month, this instalment of Curator’s Perspective will be devoted to the life and work of Carlos Ferrand, an important and prolific Latinx-Canadian filmmaker whose credits include roles on 22 NFB films.

A special focus will be placed on his film Cimarrones, in which several of Peru’s vanguard artists of the early 1980s participated. It was post-produced/completed at the NFB in 1982 thanks to Ferrand’s determination and perseverance.

For starters, I invite you to watch the most recent NFB film Ferrand directed, Greetings: Te’skennongweronne – Yves Sioui Durand (2017), a four-minute tribute to Indigenous playwright Yves Sioui Durand that brings to life the memory of the First Peoples of the Americas.

Greetings: Te’skennongweronne – Yves Sioui Durand, Carlos Ferrand, provided by the National Film Board of Canada

A Socially Engaged Peruvian Filmmaker in Exile

After completing high school in his native Lima, Peru, Ferrand moved to Syracuse, New York, and studied liberal arts. Afterwards, he returned to Lima to study cinematography with Armando Robles Godoy for a year, only to leave again to study cinema at INSAS in Brussels.

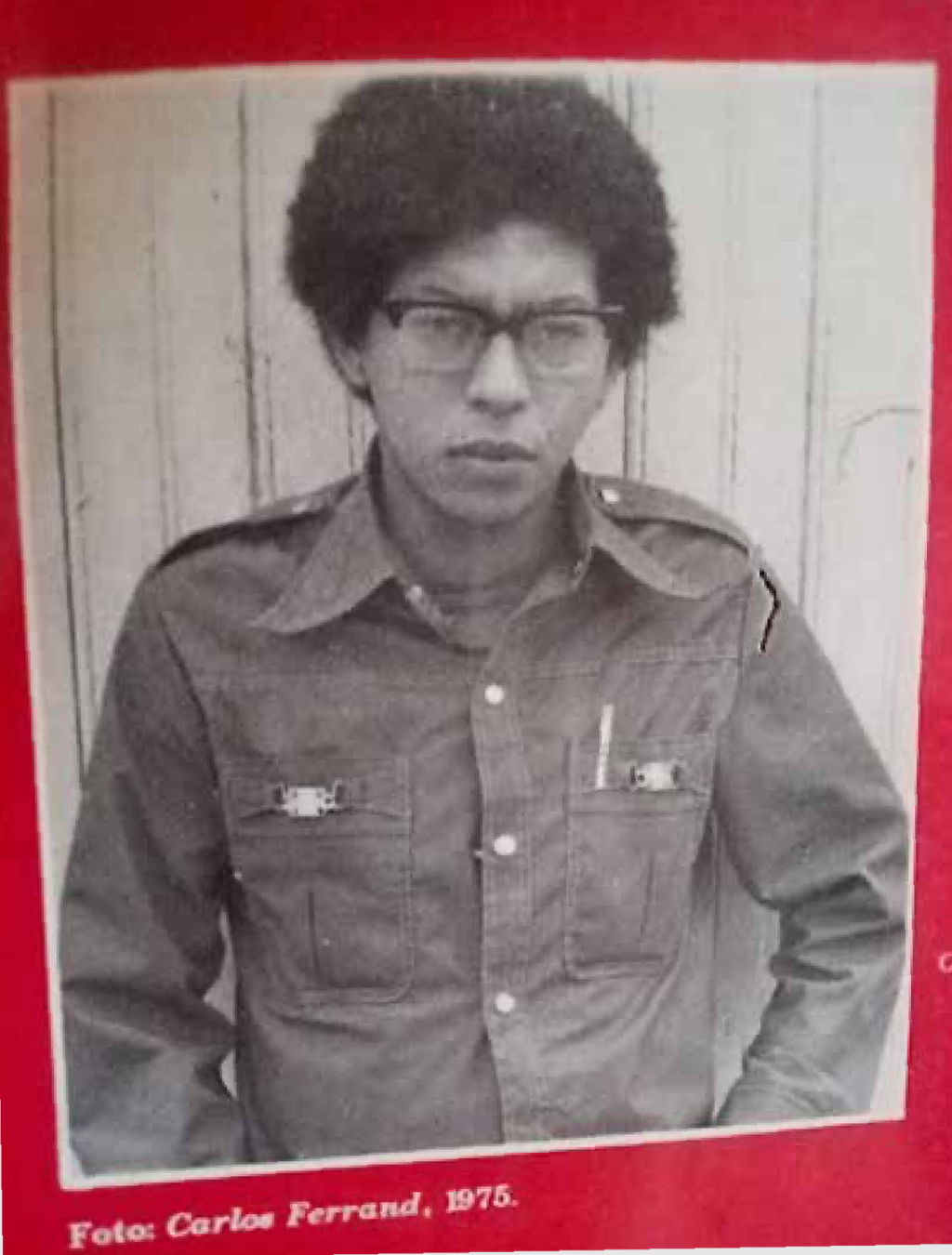

Upon completing his studies abroad, Ferrand returned home in 1970 and joined the Gobierno Revolucionario de la Fuerza Armada (Revolutionary Government of the Armed Forces), a military dictatorship (1968–1980) led by General Juan Velasco Alvarado whose radical reforms had a profound impact on Peruvian society. Ferrand directed several short films from 1971 to 1973[i] for the revolutionary government that depicted mainly the processes and results of its agrarian reform program.

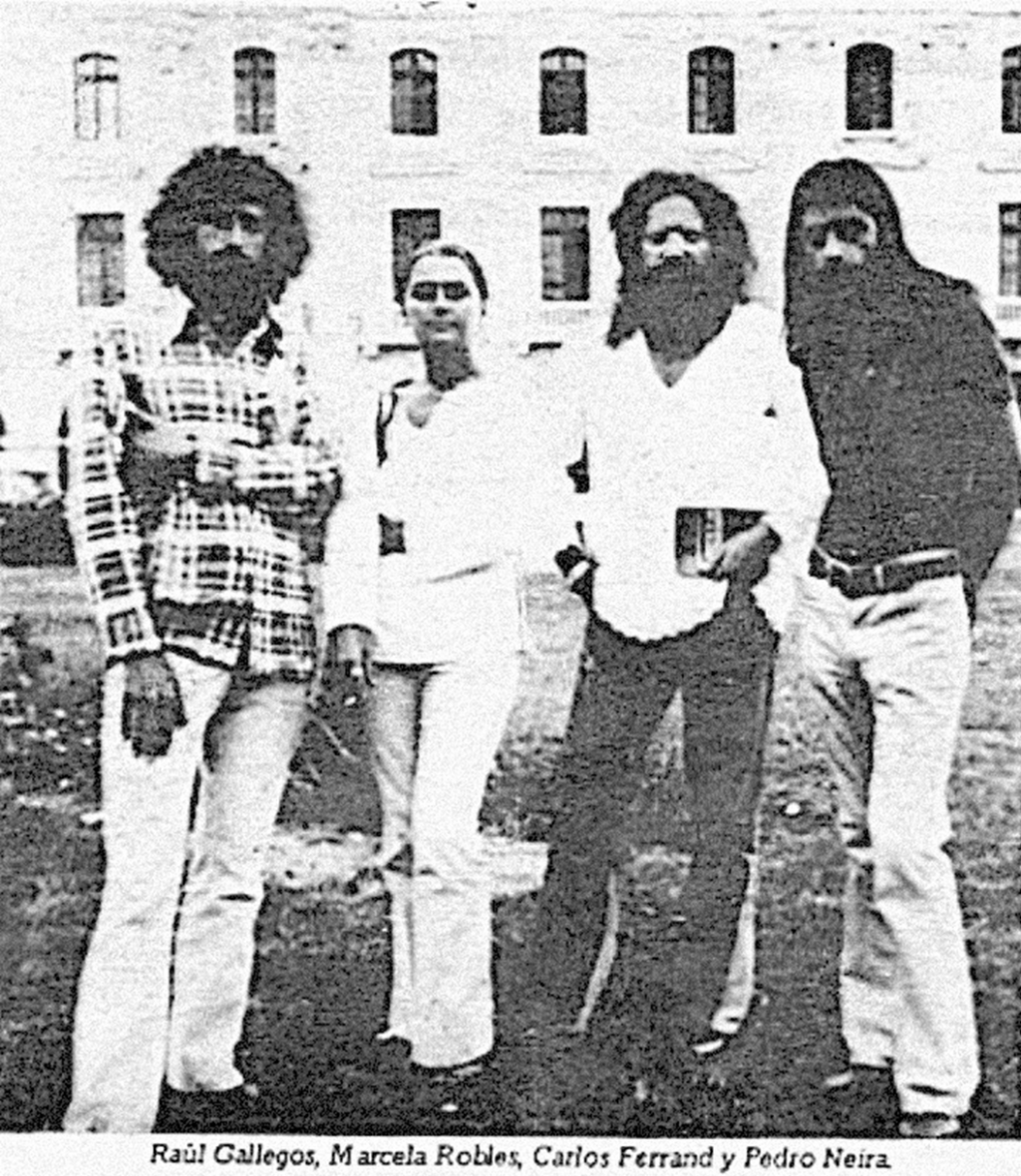

At about the same time, Ferrand, along with Marcela Robles, Raúl Gallegos and Pedro Neira, founded the Grupo cine Liberación sin Rodeos – CLSR (loosely translated as “Liberation without beating around the bush”), which became active in 1972.[ii] These four Peruvian artists made a series of about a dozen short films (1973–1976)[iii] on the life and experiences of the Andean, Amazonian and Afro-Peruvian peoples, focusing on the reforms of the early 1970s. Everything came to an end when a right-wing military coup d’état took place, and much of this film material was incinerated.

Ferrand was forced into exile, but he brought to Canada with him reels of the film he was working on at the time, Cimarrones, which would become his first Canadian film.

Cimarrones, Carlos Ferrand, provided by the National Film Board of Canada

Cimarrones and the Peruvian New Wave

Earlier this year, and thanks to a mutual friend (exiled Peruvian-Canadian poet and emeritus professor Lady Rojas Benavente), Carlos Ferrand wrote to me regarding Cimarrones: “I have tried a few times to have a short that I filmed in Peru in 1975, and which was completed at the NFB in 1982, to be included in the NFB’s catalogue and website; but nobody has ever been able to identify or locate the film within the NFB’s archives.”[iv]

It turned out that a print of the film did not exist in the NFB’s vault, but with the help of NFB’s Library and Archives, we found Cimarrones’ registry number and a production file that included two letters, one of which was internal correspondence dated April 24, 1981, confirming that the NFB was involved in the production of the film.

These documents provided the information needed for the NFB to acquire its own copies of the film, which had been recently restored and digitized by the Board with the support of an NFB colleague. Carlos Ferrand himself provided the NFB with copies in both English and French; the latter version features a French on-screen narrator (click in the image below to watch Cimarrones‘ French version).

Cimarrones is a powerful, short drama that recreates events that took place in Peru in the early 1800s, when a group of cimarrones—or runaway slaves—attacked a caravan to free friends who’d been sentenced to death. The Afro-Peruvian leader in the film is played by Amador Ballumbrosio, the elder patriarch of Los Ballumbrosio, a well-known Afro-Peruvian family from the Carmen District in the province of Chincha. The family have provided a nexus for different Afro-Peruvian artists and activists for decades, and have freely shared their knowledge to help preserve Afro-Peruvian music, cuisine, medicine and oral stories.[v]

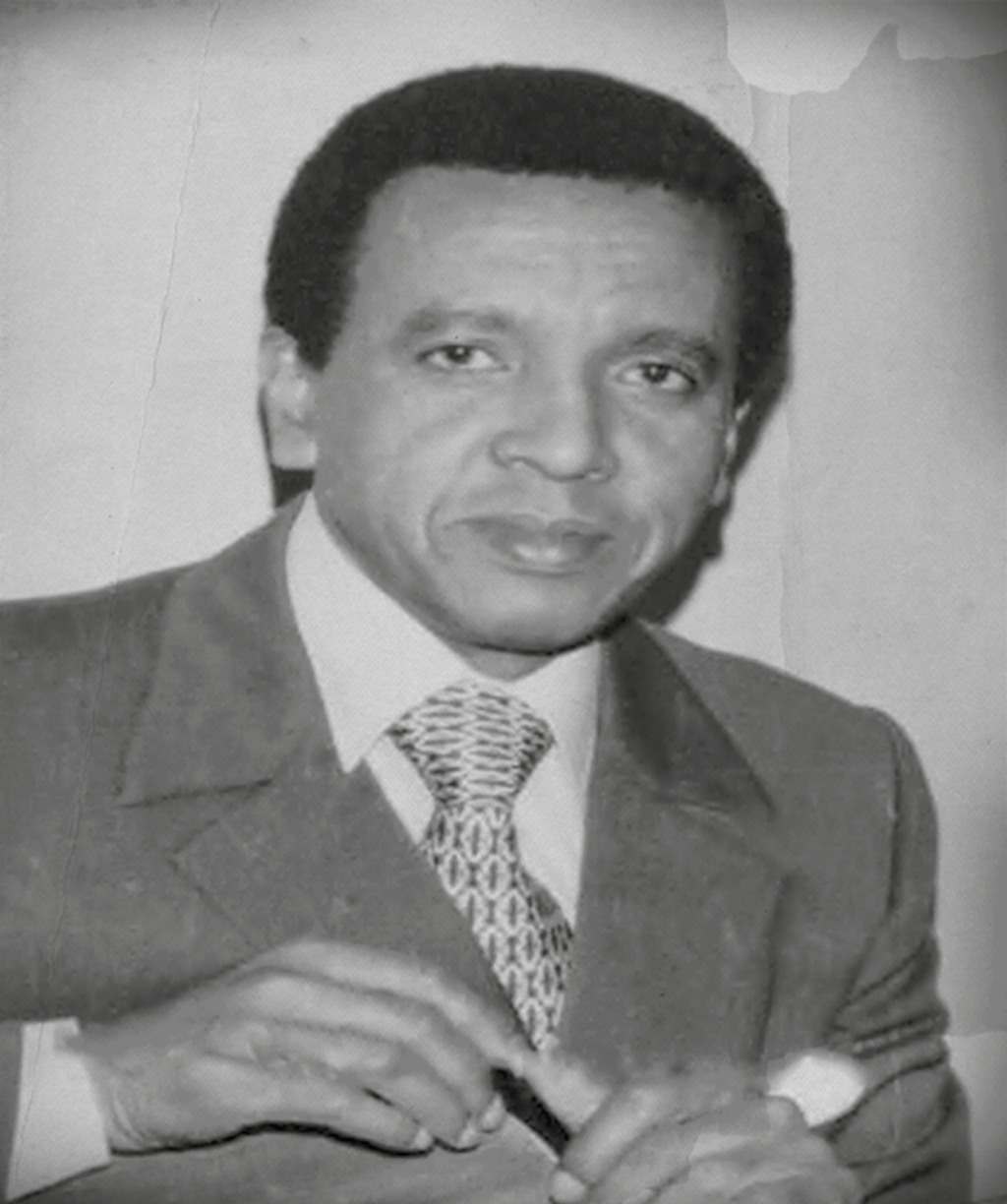

The key creatives behind the film were part of a Peruvian new wave of artists in the 1970s. Luciano Correa Pereyra is credited as researcher for Cimarrones, and the film was co-written by Ferrand and Enrique Verástegui, the iconic Peruvian (of African and Chinese descent) poet and writer of short stories, novels, essays, plays and screenplays. Verástegui also founded the Movimiento Hora Cero (Zero Hour Movement), which rejuvenated Peruvian literature, and is today considered one of the most important poets in Latin America.

The film’s music was composed by Carlos Hayre, one of the best Lima marinera (a Peruvian dance) guitarists of all time, and a great musicologist, who introduced the use of the cajón (box drum) in creole waltzes and Andean harmonies in modern jazz and bossa nova arrangements.[vi] The cajón was also used in Hayre’s soundtrack for the film.

About the soundtrack, Ferrand wrote that, “[t]he production was poor, and we couldn’t afford the instruments that Carlos Hayre needed. So, every day after midnight, we would knock on the service door of the National Symphony of Peru and, for a small fee, the guardian would let us take out the instruments with which Carlos Hayre and his musicians would play and record during the night.”[vii]

Directed and shot in 1975 by Carlos Ferrand, Cimarrones was not completed due to the coup d’état by Morales Bermudez, which put an end to the reforms launched by General Alvarado in 1968. As noted above, when Ferrand was forced into exile he brought reels of the film with him, and he was able to complete it in 1982 thanks to the support of Peter Katadotis, the English executive producer at the NFB at the time. Under the filmmaker assistance program that existed then (which predated the NFB’s official ACIC/FAP initiatives), the NFB furnished Ferrand with a studio to construct and shoot the opening scene of the film (in both English and French), and the set used for the professor’s scenes was constructed by the NFB’s art direction team in 1981.[viii] But the NFB also provided Ferrand with equipment and staff to complete the post-production activities for Cimarrones, including image correction, sound recording, sound editing and final cut editing.

This Latinx-Canadian gem has been now digitized, restored and preserved, and is being made available for free across the globe on nfb.ca!

One of the Founders of Latinx-Canadian Cinema: Ferrand and the NFB

The quality and substance of Cimarrones opened the NFB’s doors to Carlos Ferrand, who has since worked on 22 NFB films,[ix] including six as director: Greetings: Te’skennongweronne – Yves Sioui Durand (see above); People of the Ice (2003, co-director), a feature-length documentary that explores the threats of global warming to the Arctic, which has been home to Inuit for 4,000 years; Shadow Chasers (2000, co-director), a feature doc on people who are obsessed with solar eclipses; Kwekànamad: The Wind Is Changing (1999), about Annie Smith St-Georges, an Algonquin mother and wife who wants to restore her people’s ancestral pride and dignity by building a 10-storey glass teepee to house the National Aboriginal Arts and Performance Centre in Ottawa; Cuervo (1990), about a woman who hires a private detective to track down her long-lost twin sister, leading her to the Amazon forest and strange phenomena; and The Man Who Talks with Wolves (2001), which takes us into a mysterious world where the line between human and beast becomes blurred.

The Man Who Talks with Wolves, Carlos Ferrand, provided by the National Film Board of Canada

Ferrand has been the subject of many recent tributes and honours around the world, including a permanent exhibition of some of his photography work at the prestigious Reina Sofia Museum in Madrid; a retrospective curated by the Lima Film Festival in 2018 that screened restored versions of the films he made with Grupo cine Liberación; and the inclusion of a restored version of his film Niños in a retrospective on the roots of Latinx-Canadian filmmakers, presented at a National Gathering of Latin Canadian Filmmakers, organized by Cecilia Araneda and Zaira Zarza in Montreal earlier this year.

The NFB has joined these celebrations of Ferrand’s work by acquiring, restoring and making some of his films available during Latin American Heritage month, and we invite the public to get to know more about the life and work of this seminal Latinx-Canadian filmmaker. Stay tuned for other blog posts about Latinx-Canadian artists at the NFB; for now, you can visit Latinx-Canadian Cinema and NFB Abroad: Latin America on Screen, two channels we’ve curated to mark this month, where you’ll find even more films offering unique Latin American perspectives and experiences.

¡Salúd!

[i] As screenwriter, director, cameraman and editor (1971–1973): Trabajo voluntario (35mm, 20 min., B&W); Voto del Analfabeto (35mm, 15 min., B&W); Con la reforma Agraria (16mm, 9 min., B&W); and, Casa de Madera (16mm, 17 min., B&W); while the film Niños was a collective work of the group “Liberation without beating around the bush”, shot in 35mm, 18 min., B&W, fiction).

[ii] https://ata.org.pe/persona/grupo_de_cine_liberacion_sin_rodeos/ (Picture Ferrand, Carlos. Cimarrones (film book). Produced for a public screening of the film at SBC galerie d’art contemporain in Montreal in 2021.)

[iii] As co-director and cameraman, with the Grupo de cine Liberacion sin Rodeos (1973-1976): No Alineados (35mm, 12 min., colour); Javier Heraud (35mm, 19 min., colour); Somos mas de lo que se piensa (35mm, 12 min., B&W, fiction); Delfin (35mm, 17 min., B&W); Vision de la Selva (16mm, 20 min., B&W); and Racrachacra (16mm, 18 min., B&W).

[iv] Personal email, November 5, 2023.

[v] Di Laura, Giancarla. “La casa de Adelina y Amador,” Sudaca: Periodismo libre y en profundidad, May 4, 2024.

[vi] Ferrand, Carlos. Cimarrones (film book). Produced for a public screening of the film at SBC galerie d’art contemporain in Montreal in 2021.

[vii] Ibid (Picture IBIDEM).

[viii] Ibid

[ix] Carlos Ferrand’s cinematographer, image and other credits at the NFB: Malartic (2024, credited as “conseil à la réalisation”); Michaelle Jean: A Woman of Purpose (2016, credited for additional images); A Monk’s Secret (2009); Leonard Forest, Filmmaker and Poet (2006, credited for additional images); Encounter with an Algonquin Sage (2000); Dark Intent (2000); La loi et l’ordure (2000); Rupture (1998); Père pour la vie (1998); Les désoccupés (1997); Baby Business (1995); Un léger vertige (1991); The Impossible Takes a Little Longer (1986); Doctor, Lawyer, Indian Chief (1986); Les Filles aux allumettes (1986).