Gil’s Gift

Gil’s Gift

Gil Cardinal — fearless filmmaker and big-hearted mentor to generations of Indigenous artists — has left us.

He died in his hometown of Edmonton on November 21, and while scores of friends and admirers across Canada and around the world are mourning their loss, they are also celebrating his singular and enduring achievement.

“Gil’s legacy is huge,” says Jesse Wente — Ojibwe cultural critic and current Director of Film Programmes at the TIFF Bell Lightbox. “Gil was part of that very small group, along with Indigenous filmmakers like Alanis Obomsawin and Merata Mita, who really did break new ground. He was among the first filmmakers to put our stories onscreen, stories that came from and spoke to the Indigenous experience.”

Born to a Métis mother and raised by a non-Native foster family, Cardinal embodied the complicated history of Canada’s Indigenous peoples, and he would mine this terrain in both documentary and fiction, creating a vital and invaluable body of work. His impressive list of credits includes NFB releases like The Spirit Within, David with F.A.S. and Totem: The Return of the G’psgolox Pole, along with big budget TV projects like Big Bear and Indian Summer: The Oka Crisis, and numerous episodes of North of 60 and The Rez.

His 1987 auto-biographical film Foster Child, now recognized as a landmark Canadian documentary, would chart his efforts to renew contact with his original Métis family and culture. Tracking down hitherto unknown relatives across rural Alberta, “the places that I could have come from,” he tenderly and unflinchingly pieced together the fragmented story of his birth family.

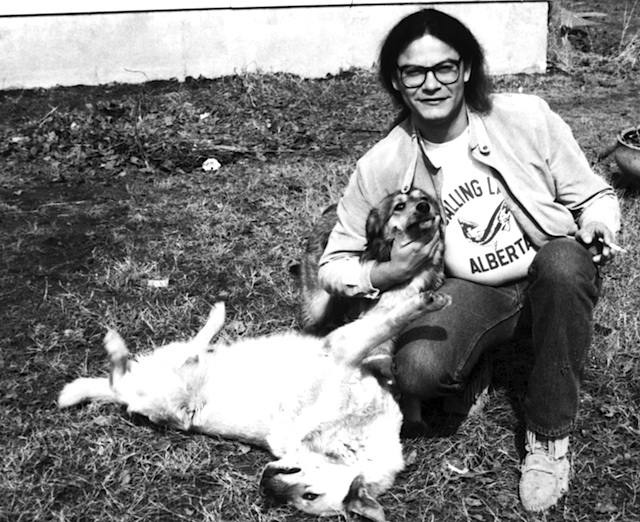

In one pivotal scene, exemplifying his unique blend of skill and courage as a filmmaker, Cardinal allows viewers to witness the moment he first sees an image of the late Lucy Cardinal, his birth mother. He opens a family album, and there it is: a simple black-and-white snapshot, modest but containing a universe of meaning, of a pretty young woman, basking in the glow of an Alberta summer, long before life dealt the hard blows it had in store for her. We watch the complex play of emotions on Cardinal’s face as he cradles the object like a tiny icon, gazing for the first time upon this image, this woman who brought him into the world. It is an intimate and powerful moment — an astute observation of the evocative power of photography, and a remarkable instance of documentary cinema.

Cardinal was awarded the 1988 Gemini for Best Direction for his work on the film, and Foster Child circulated to universal acclaim on the global festival circuit, winning over ten international awards, including a Special Jury Prize from the Banff Television Festival.

“Foster Child is one of the great docs to come out of Canada and nobody but Gil could have made it,” says Wente, who included the film among the titles he showcased in First People: 1500 Nations, One Tradition, a major retrospective of international Indigenous cinema presented by TIFF in 2012. “It was a deeply meaningful film, particularly for young Indigenous people like me, kids who loved movies but who saw no reflection of their lives in Hollywood films. Gil made it possible for us to think about putting our own stories on the screen, and that was something new and important.”

“Brave and beautiful and big”

The NFB provided Cardinal with a creative base throughout a prolific career that spanned three decades, and Bonnie Thompson, a producer at Edmonton’s North West Studio, was among over 100 film professionals who came together on November 7 when the Alberta Media Production Industries Association (AMPIA) honoured Cardinal with the 27th Annual David Billington Award.

“Gil’s work was brave and beautiful and big – and it touched many thousands of people,” she says. “In the years before the Royal Commission on Aboriginal People or the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, Gil was out there, challenging the ways that Indigenous people were misrepresented in mass media, creating ways for Aboriginal communities to see themselves in a new light and to reclaim their place within Canadian society.”

“He was a lovely guy, quiet and understated but with this big presence,” she recalls. “In the early days I used to envy my male colleagues when Gil would greet them with a ‘Hey Boss.’ It was a joke, because we all knew that nobody was Gil’s boss. Then one day, while we were working together on Totem (pictured above), he popped his head into my office and said, ‘Ready Boss?’ That small gesture meant a lot to me. I respected him so much: it felt like I’d somehow earned my stripes as a producer.”

A nurturing ethos

Cardinal will be fondly remembered as a generous mentor and teacher. “His whole ethos was embedded within the idea of community, and that showed not only in his films but in how he worked,” says Wente. “He was a genuinely nurturing figure in an industry where nurturing is not always the norm, and it’s been great to see the outpouring of gratitude from so many Indigenous film professionals, people who got their start in junior positions on Big Bear or Indian Summer. There’s a whole generation of Indigenous film people who owe him a debt.”

TIFF has presented a number of Cardinal’s films over the years: The Spirit Within, in 1990; Tikinagan, in 1991; Totem: The Return of the G’psgolox Pole, which got its world premiere at TIFF in 2003.

In a concrete gesture that honours Gil’s life work, the AMPIA has recently announced the establishment of the Gil Cardinal Legacy Fund, which will provide support to emerging Aboriginal filmmakers.

For those who have not yet seen the extraordinary Foster Child, and for those would like a second viewing, here it is:

Foster Child, Gil Cardinal, provided by the National Film Board of Canada

Photo portrait of Gil Cardinal: Debbie Boccabella