Michaëlle Jean: A Woman of Purpose | Interview with Jean-Daniel Lafond

Michaëlle Jean: A Woman of Purpose | Interview with Jean-Daniel Lafond

We all know the Governor General of Canada’s role is to represent the Queen, but how well do we know the position really? What are the constitutional and ceremonial duties involved? Can the appointment have real impact for Canadians?

The NFB has just launched an intimate and sensitive doc that answers these questions and many more. Titled Michaëlle Jean: A Woman of Purpose, the film zooms in on former Governor General Michaëlle Jean, who held the position from 2005 to 2010.

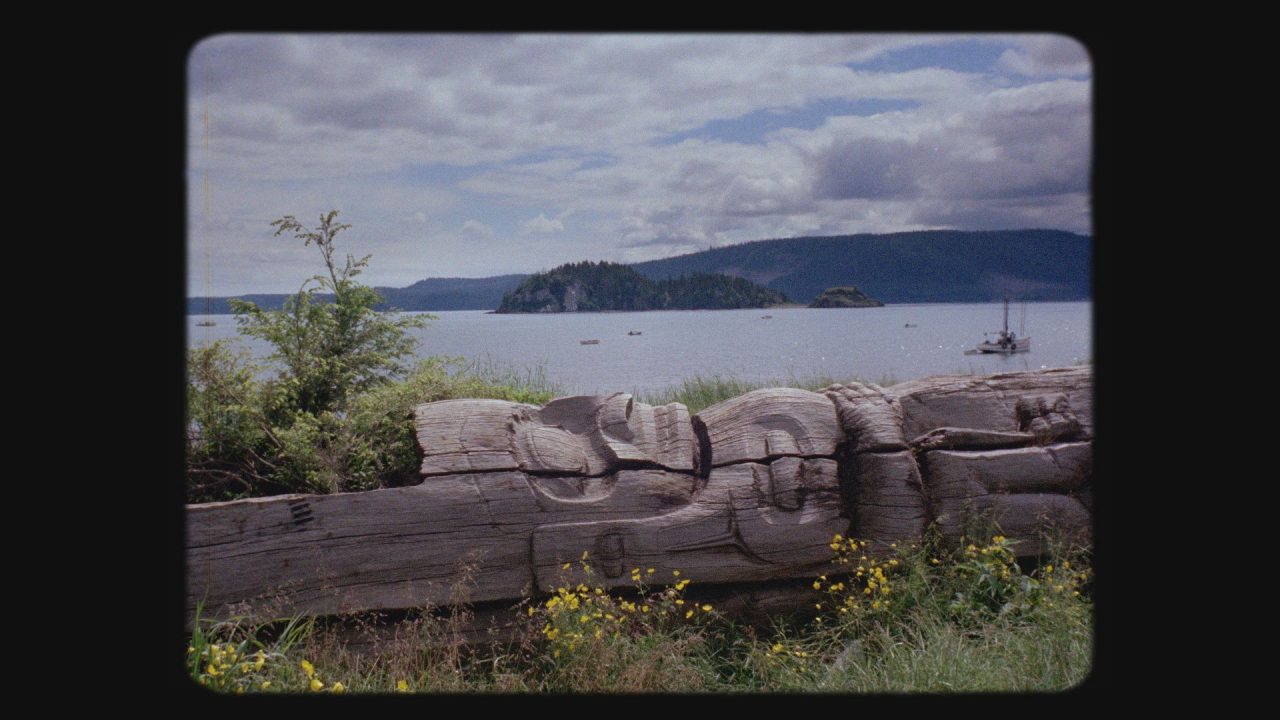

A social activist, global citizen, and black woman, she would redefine the possibilities of that office. While her national priorities were at-risk youth, women, and Indigenous peoples, her international success came from her cultural diplomacy.

She brought a message of hope to citizens in the 40 or so countries she visited during her mandate, and in regions as disparate as the Far North and Africa. Michaëlle Jean was also deeply affected on a personal level by the terrible earthquake that ravaged her native land of Haiti during the last moments of her term.

Below is an interview with Jean-Daniel Lafond, who is both the film’s director and Michaëlle Jean’s spouse. The interview was led by Helen Faradji, in collaboration with Catherine Perreault.

NFB: Can you tell us how the idea for the film originated?

Jean-Daniel Lafond: I didn’t know from the start that I was going to make this film. My wife was thrown into the role of Governor General without having considered herself a candidate—and her appointment was as unexpected for her as it was for me. When I heard the news, I was shooting Le Fugitif ou les vérités d’Hassan (American Fugitive: The Truth About Hassan) in Washington and developing my next film, Folle de Dieu (Madwoman of God). We spent eight days tucked away in our cottage thinking it over, and we were very much aware right from the start of the symbolic importance of this choice: she is a very socially engaged woman, she is black, and both of us were born outside the country. This would present a very encouraging image for people born outside of Canada. They would be able to tell themselves, for instance, that “Canada is a land where everything is possible.”

This powerful symbolic importance made the offer hard to resist—but it also made it hard to accept right away! Accepting meant changing our lives and our relationships with people, while remaining true to ourselves and not betraying our values and commitments.

When Michaëlle, and I, said yes it was because we were confident it was possible to fulfil the duties of the post in a particular way. Beyond presenting honours and awards, signing decrees, and swearing in governments—beyond formal ceremonies, welcoming visiting heads of state and making state visits to countries around the world, there is space for creating your own approach.

And when we said yes, we did it with a very clear moral compass, that we would be citizens among citizens. It was in that spirit that Michaëlle devoted a large part of her mandate to listening to citizens—to ensuring that the voices of those who are rarely or never heard are truly listened to: young people, Indigenous people, those who are generally excluded from the conversation.

For my part, over the five years I was able to organize more than 50 forums (called The Power of the Arts), across the country and abroad, bringing together filmmakers, writers, artists, thinkers, and other creators to bring to the fore the idea that the arts, culture, and education are our true (and peaceful) weapons of mass construction.

NFB: And how did the idea of collecting images during the mandate come about?

JDL: In the beginning, we were followed by Army photographers who took “beautiful” and carefully posed images. That really didn’t do justice to the great diversity of our interactions with Canadians. I decided to try doing some filming myself. But it was complicated being in the spotlight, among members of the public and journalists, and holding a camera at the same time. So we asked the photographers to transform themselves into videographers, but without completely abandoning photography. The idea was to keep a record and assemble audiovisual material for the archives.

At the same time, we created a website linked to the Governor General’s official site. It was called Citizen Voices (À l’écoute des citoyens in French), included video clips of all her events with citizens, and served to launch an interactive dialogue between the Governor General and members of the general public.

At this point, I had no intention of making a film. I wanted to bring together images for archival purposes that would capture the scope of the position and its functions. Although the quality of the visuals and audio varies quite a bit, this archival footage nevertheless represents a valuable—I would say unique—recollection that fills the gaps and omissions when it comes to media representations of the Governor General’s function. Some of this archival material is in my film and there is also a selection on the former Governor General’s website, which includes Citizen Voices.

NFB: What did your behind-the-scenes point of view allow you to capture?

JDL: My film is made up primarily of images I shot myself after the end of my wife’s term, between 2010 and 2015. I didn’t want to make a film about our private lives. Above all, what I wanted to do was return to my role as filmmaker and cast my eye back on what I had experienced while sharing the life and actions of the 27th Governor General of Canada: the tête-à-têtes, the solitary moments, moments of joy and of pain. Mostly, I wanted to understand this force that animates her, that makes her reach higher—her capacity to both bring together and resist. In short, underlying it all is a committed woman who I tried to understand. That’s what was important to me. I haven’t tried to present a chronological or exhaustive account. Beyond laughing or crying—unlike in my other films—I’m trying to understand and, further, to help others understand.

NFB: You lived through all this at your wife’s side. How do you find the necessary distance to approach a subject with whom you are so close? Were there any particular traps you needed to avoid?

JLB: I needed a certain amount of distance to make this film. It took me five years to reach what I call a good distance. The Haitian portion, for example, is shot between 2011 and 2015, which allowed me to put things in perspective and to tell a story—build a narrative. When we left Rideau Hall in 2010, the idea of making a film was there, but I couldn’t see what kind of shape it would take, or what its intention would be. For the next two years I put the idea aside while I was busy working on creating our legacy project, the Michaëlle Jean Foundation, which is devoted to helping young people in difficult circumstances. Little by little, I started looking at some of the archival material. But the archives are not the same as a film: there is no point of view and there is no narrative intent.

After Michaëlle’s term ended she was named—literally, the next day—UNESCO Special Envoy for Haiti. She was not in a position to quickly put into perspective her five years as a stateswoman. I accompanied her several times to Haiti, and without her really being fully aware of it, gradually started filming by myself, in dialogue with her, in the country that has led her to feel so much pain, but is also the source of her resistance and energy.

I had the vision of the film I wanted to make while I was there: in the ruins of Port-au-Prince, in the warmth of Jacmel, in the dazzling beauty of Ile à Vaches. And I started filming while her attention was absorbed by the reconstruction mission in her country of origin. The contrast between beautiful Haiti and suffering Haiti, between life and death, between Eros and Thanatos created the right distance for this film to happen… with her.

I remember that near the end of her term as Governor General, a well-intentioned producer approached me about making a “funny and entertaining” film on the role of the Governor General. But I’m not Infoman! [A Quebec TV show satirizing current events.] I preferred to work alone, freely, without any constraints on the production until my long-time collaborator Babalou Hamelin and I had the first cut. What really interested me was not the clichés, but what is left unsaid. Caricature is definitely easier. It’s much simpler to make just an image than to make the right image. But it’s that endless quest for the right image that makes the art of documentary great, and that reveals truths—if not the truth. That’s what drives me.

NFB: Can you talk about the main values that Michaëlle Jean succeeded in promoting over the course of her term?

JDL: Michaëlle in real life is as she appears in the film. She does not take her commitment or her determination lightly. Besides, she isn’t a politician—she’s a diplomat. She really is there to bring people together and not to divide them. That’s what really impressed me as I looked over the archival footage and remembered those five years. I saw someone in search of fraternity, solidarity, and freedom; a woman who advocates for the idea that exclusion is not a solution and that it is always possible to rehabilitate and reintegrate into society those who have been excluded.

Yes, there was symbolic importance in naming a black woman to the post. But she had never been nor was going to be a token black woman, and she quickly transcended the symbolism. When she spoke in 2005 of “breaking down solitudes,” she was raising a question that remains crucial in our society and in the world at large: How do we succeed in creating a harmonious and peaceful way of living together? She brings these same values and the same question to her work today as Secretary General of the Francophonie, which brings together 80 countries.

NFB: Your film also highlights her rather remarkable level of personal integrity…

JDL: Yes! I never had any doubts about her integrity, even when I questioned her on it. To what point can you maintain your integrity in a public post? During over 40 state visits I crossed paths with liars, manipulators, and arrogant politicians—but I also met many genuine men and women in politics, who were truly upstanding and devoted to public service. And along the way I watched this woman in an environment in which being a woman comes with its share of difficulties. I saw how she stood tall and succeeded in gaining respect simply by being herself. Yes, she could be very emotional and had difficulty holding back tears during a press conference after the Haiti earthquake—but that’s not a weakness. It’s a natural expression of her character that some would have preferred to not see. Her integrity rests on the sincerity of her relationships with others, and her respect for herself and for the Other.

NFB: On the subject of Haiti, you already directed La manière nègre ou Aimé Césaire, chemin faisant (A State of Blackness: Aimé Césaire’s Way) and Haïti dans tous nos rêves (Haiti in All Our Dreams), in which Michaëlle Jean is present. But where, in the past, you presented her in the context of literary figures who left their mark on her, this time the connection to Haiti is much more organic. Can you tell us about both your and Michaëlle Jean’s relationship to the country?

JDL: I’ve often said I have three loves: Quebec, Haiti and France. Haiti is a difficult and painful love. I’ve followed and lived through all the dramatic events that have taken place since Duvalier, the son, left in 1986. But it’s also through Haiti that I met Michaëlle. In 1990, when I was a journalist, I asked her to accompany me there as a collaborator to work on a film. And we’ve been together ever since. I feel a kind of solar, sensual love for this fragile and elusive country that may bend, but does not break—that refuses to get on its knees and submit.

This sense of resistance is really evident among Haitian women. In a scene shot in Port-au-Prince during a massive rally on March 8, 2010, Michaëlle spoke in Creole and addressed the women, saying, “I am very proud to have been born from the womb of a Haitian mother.” And she paid tribute to women’s resistance and their ability to carry the country on their backs and its future in their bellies. She added that when Haiti emerges slowly, bit by bit, it will be because of the women.

Having lived through those moments and then looking back at this scene, I grasped Michaëlle’s secret: her service as Governor General was rooted in her experience as a Haitian woman—with a capacity to resist ill winds and to advance the issue most fundamental to her (which I share as well): making humanity a little more human.