Resurrecting Gertie the Dinosaur

Resurrecting Gertie the Dinosaur

Through the combined efforts of the Cinémathèque québécoise and the National Film Board of Canada (NFB), with support from the University of Notre Dame in the United States, an animated film once thought lost—Gertie, by Winsor McCay—has been brought back to life. Completed in the spring of 2018, this colossal undertaking spanned three years and has added a new page to the history of animation.

Gertie is the original film out of which McCay created his masterpiece, Gertie the Dinosaur, a few months later. That the latter film still exists is also thanks to the Cinémathèque québécoise, which acquired the invaluable footage in the 1960s. It was subsequently restored for the Cinémathèque in 2015 by Éléphant, mémoire du cinéma Québécois, a philanthropic organization dedicated to preserving Quebec’s cinematic heritage.

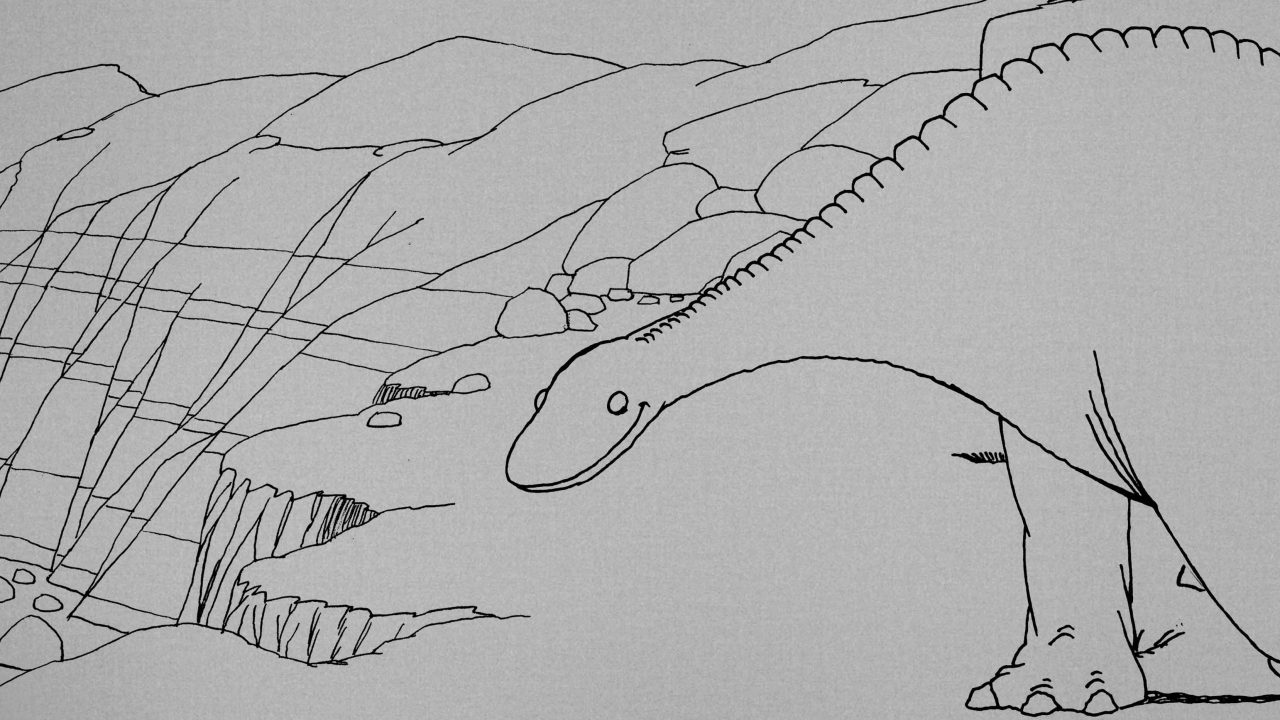

Today, Gertie the Dinosaur is considered a classic of animated cinema.[1] Made in 1914, the film is important not only for its unique qualities (realistic motion, in particular) but also for its protagonist, Gertie, who’s said to be the first character in the history of animation to have personality traits. Gertie the Dinosaur is in the public domain and can easily be found on the Internet.

As mentioned above, this film was based on an earlier version called Gertie, which McCay incorporated into his vaudeville act, announcing to the audience that he would bring a dinosaur back to life. A projection of the animated creature would then appear behind him. Gertie was an endearing female dinosaur who could be capricious at times. McCay interacted with her on stage, asking her to bow to the audience and do tricks, congratulating her, and lecturing her when she behaved badly. This entertaining, magical, and rather hilarious performance prefigured the use of projected moving images in the theatre.

McCay made Gertie the Dinosaur using excerpts from the original film, inserting intertitles (each of which involved removing several images) and deleting the final “encore” scene. McCay also added a live-action introduction so that the film could be screened without an actor on stage. Unfortunately, the original Gertie didn’t survive all these cuts and changes.

The project to reconstruct the original Gertie was driven by US psychiatrist David L. Nathan, a fervent proponent of McCay’s work, especially Gertie the Dinosaur. Having heard about Nathan’s efforts, animation historian Donald Crafton, working out of the University of Notre Dame, picked up the ball and tried to assemble the means to bring the project to fruition. The Cinémathèque québécoise immediately came to mind, as it had played such a vital role in preserving McCay’s works and archives. Soon after, the NFB’s resources and talents were also called upon to help reconstruct the film. Montreal had the intellectual, archival, and technical means to meet the challenge.

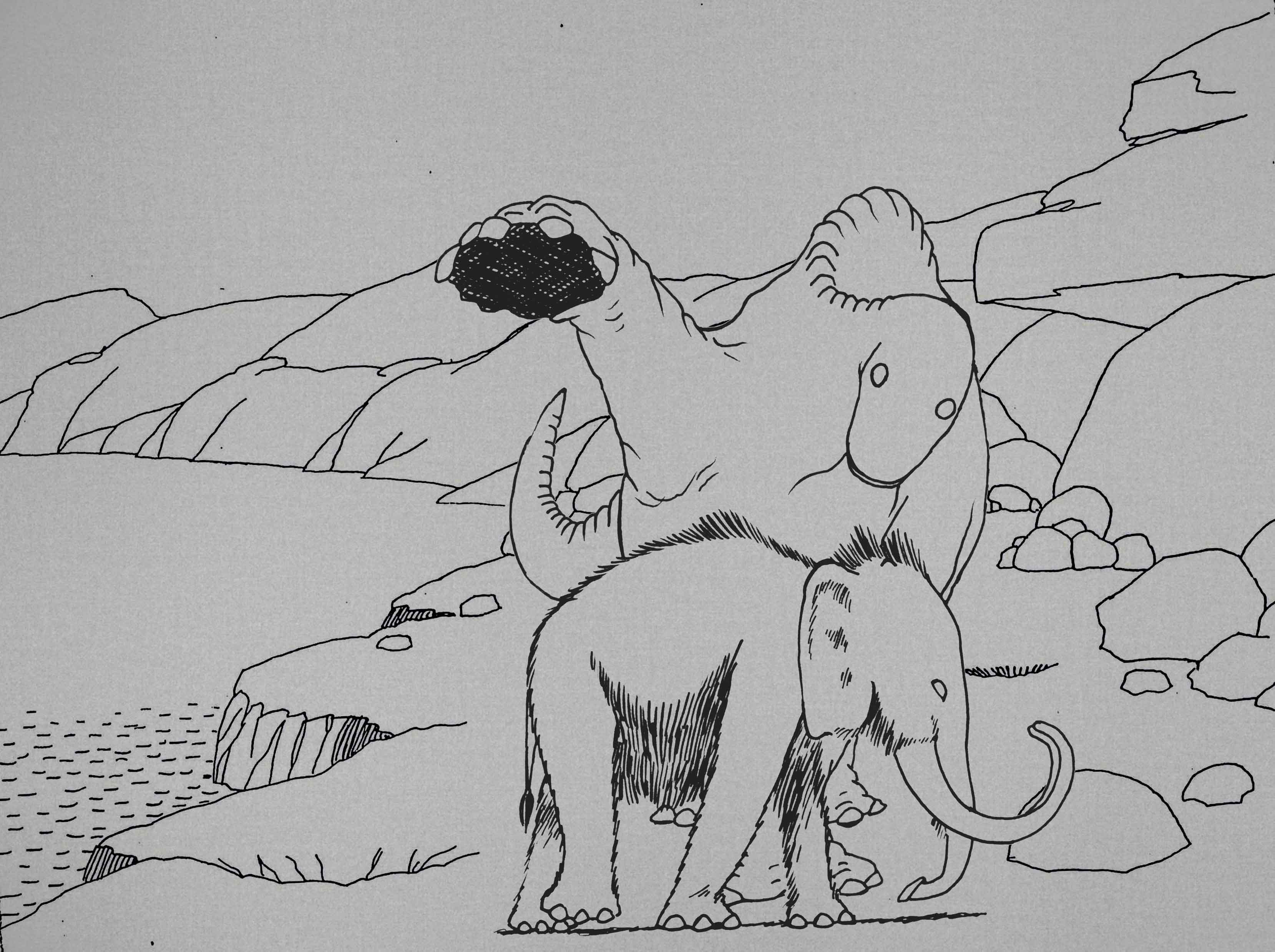

A Canada-US committee consisting of three people (Donald Crafton, David L. Nathan and me) was formed in 2015 to oversee the project. The work involved creating a 2K digital version of the film acquired by the Cinémathèque québécoise (and stored at Library and Archives Canada) and removing the intertitles and live-action prologue. The first stage (cleaning and colour correction) was done by Eloi Champagne and Sylvie Marie Fortier at the NFB. The missing drawings (about 200, including the encore scene) were then created by hand by animator Luc Chamberland, who tried to reproduce McCay’s sense of style and motion, to restore the fluid movement seen in the original. Several digital copies of existing drawings were used, including some from the Cinémathèque’s archives.

Based on research by Nathan and Crafton, and on documents from the Cinémathèque’s archives, we were able to determine, with a reasonable amount of certainty, how many drawings were missing. These drawings were necessary to restore Gertie’s fluid motion and recreate the final encore scene, where Gertie comes out of her cave and bows to the audience.

As a result of all this work, audiences now have the opportunity to rediscover this amusing short film and dazzling piece of early 20th-century stagecraft. As Crafton wrote, “In 1914, no entertainment attraction was as uniquely spectacular as Gertie, the creation of famed newspaper cartoonist Winsor McCay.” A score written by composer and pianist Gabriel Thibaudeau accompanies the show, which runs 12 minutes. Crafton also wrote a one-hour comedy about Winsor McCay’s life, which ends with the showing of Gertie.

Since the premiere of the reconstructed film, which closed the 2018 Annecy festival, McCay has been played by US actor Anthony Lawton (Annecy and Pordenone), Dutchman Eli Thorne (Amsterdam and Brussels), German Eftychia Charalampidou (Tübingen), and Quebecois Stéphane Crête (Montreal). Before long, it will be young Gabriel Krut’s turn to incarnate McCay at the Linwood-Dunn Theatre at Hollywood’s Academy Film Archive as part of The Reel Thing‘s 2019 program.

Here’s to Gertie’s resurrection!

[1] Proof of the film’s importance: it has been listed in the Library of Congress National Film Registry since 1991.