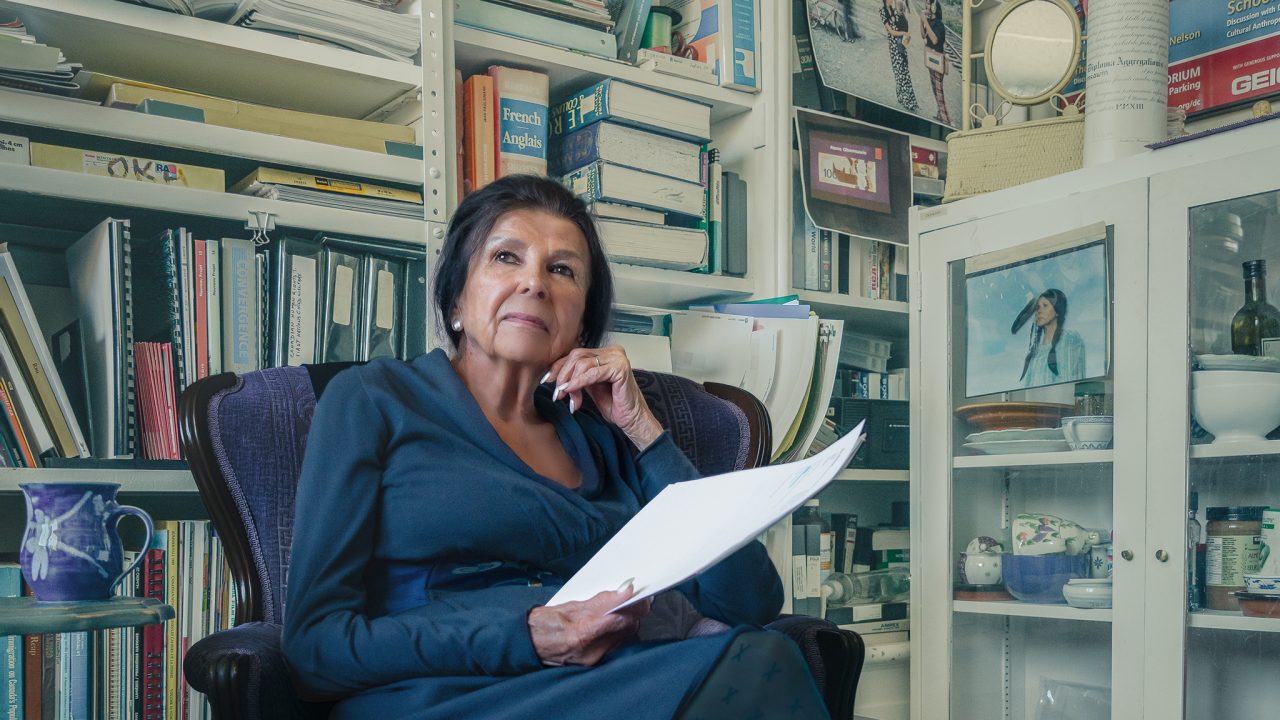

Where the Sun Rises: The Films of Alanis Obomsawin

Where the Sun Rises: The Films of Alanis Obomsawin

When asked about her creative process, Alanis Obomsawin, the renowned Abenaki filmmaker, always says that first she listens—without a camera in the room—to people share their stories. Throughout her remarkable documentary filmmaking career, Alanis has listened to the voices of thousands of individuals, each with a story to tell.

Many of these are voices of people who have been deliberately silenced and ignored, or of those too young to be heard. Very often, the voices belong to Indigenous people from across Canada, impacted by the generational effects of colonization, displacement, and assimilation, but who continue to fight to assert their rights and their dignity.

WATCH: Alanis Obomsawin’s body of work is now available online

Alanis Obomsawin was born in Abenaki territory in New Hampshire during a total eclipse—an exceptionally fitting start to an exceptional life. She grew up in Odanak, Quebec, and moved as a young child with her family to the city of Trois Rivières. Hers was the only First Nations family in her neighbourhood, and Alanis was frequently bullied by other children at her school. Alanis’s early years were filled with stories of her ancestors and Abenaki histories and folklore. She listened intently to these stories and the manner in which they were told, a unique structure and cadence that would come to inform her filmmaking in later decades.

A celebrated singer in her early career, Alanis would visit classrooms to sing and tell stories to children across the country. A concern for children’s education has been central to Alanis’s life and career from the very beginning. In the 1960s, a CBC documentary about her campaign to build a swimming pool for the children of Odanak brought her to the attention of two producers working at the National Film Board of Canada. In 1967, she accepted her first contract at the NFB, working as a consultant on a documentary about a First Nations community. Not comfortable with that role, she would soon begin work on her first documentary, Christmas at Moose Factory (1971), and would embark on a prolific, extraordinary filmmaking career that would come to have a profound impact in Canada and around the world.

With Christmas at Moose Factory, Alanis brought to light the stories of Cree children held in a residential school in Moose Factory, Ontario. Rarely—if ever—had the voices and dreams of Indigenous children in these institutions been heard. In 2019, Alanis completed her 53rd film, Jordan River Anderson, The Messenger, part of a recent cycle of documentaries that examine the rights of Indigenous children and youth and their power in shaping current and future policies.

It’s no surprise her recent work has returned to her deep-rooted concern for the lives of children. A mother herself, Alanis has long championed the rights of the young, which is evident in her filmography, from the gentle portraits in Mount Currie Summer Camp (1975) to the heartbreaking Richard Cardinal: Cry from a Diary of a Métis Child (1986), and to Sigwan (2005), an experimental film and one of only two fiction works Alanis has created. The epic Our People Will Be Healed (2017) and the hopeful Jordan River Anderson, The Messenger demonstrate the injustices faced by Indigenous children and the urgent need to do what is right.

Our People Will Be Healed, Alanis Obomsawin, provided by the National Film Board of Canada

Alanis has often said that a picture may say a thousand words, but a voice is specific; it says precisely what is intended, with little room for interpretation. The manner in which she listens to the spoken word of Indigenous people is evident in the collections of short documentaries within the L’il’wata and Manawan series, made early in her career. These insightful (and often playful) documentaries depict the complexities, realities, and beauty of the Indigenous nations they reflect, and continue to have relevance in the present day as the quest for justice and protection of rights for Indigenous languages, cultures, and land goes on. In these works, one experiences Alanis’s powerful yet gentle cinematic voice exploring its range.

The same can be said of Amisk (1977) and Mother of Many Children (1977), the latter of which was a milestone in Alanis’s career as her first feature-length film and a classic of Canadian documentary. It explores significant themes of the matriarchy and the vital importance of women in Indigenous cultures, while reflecting on themes of mother and child, which resonate throughout Alanis’s works, including her printmaking.

To look at her body of work is to see a representation of a tremendous period of change for Indigenous people and nations in Canada. This cannot be overstated.

Throughout her life, well before taking up the camera, Alanis was an activist, taking a stand against injustices perpetrated against others. She witnessed a changing world that continues to evolve today; a world very different to the one she grew up in and to the one in which she began her film career.

An incident in the summer of 1981 would further galvanize the connection between her activism and her art. When the Quebec provincial police raided Listuguq, a Mi’gmaq community, in opposition to their inherent fishing rights, Alanis created her most searing and impassioned documentary to date. Incident at Restigouche (1984) is social-protest film at its most potent and features an unforgettable encounter between Alanis Obomsawin and Lucien Lessard, the Quebec Minister of Fisheries who ordered the raids. With Incident at Restigouche we witness a turning point in her work as she fully embraces the power of film as a tool for social justice.

Throughout her career to this point, Alanis had to fight to claim space. It was not always easy. The success of Incident at Restigouche was a pivot point in her career from which she was given greater means to make the films she chose. It was a hard-fought battle and one from which we have all benefited. In the 1980s, Alanis continued to make socially relevant and highly impactful work, including Richard Cardinal, which led to legislative change in Alberta, Poundmaker’s Lodge: A Healing Place (1987), one of the first documentaries to examine how systemic racism can lead to addiction, and No Address (1988), which presented humanistic portraits of homeless Indigenous people in Montreal.

But it was the events of the summer of 1990 in Oka, Quebec, that would ultimately give Alanis’s work a heightened international profile and cement her status as one of the world’s foremost activist filmmakers. The Kanienʼkehá꞉ka (Mohawk) resistance in Oka would come to define contemporary relations between Indigenous people and the rest of Canada, and would inspire a new generation of Indigenous activists who have come to shape our present-day politics. Alanis created four films on this remarkable time in Canadian history, including the now-seminal Kanehsatake: 270 Years of Resistance (1993), a true classic of documentary cinema and a vital work in international Indigenous cinema.

Alanis has an intense drive and passion to tell these stories because there is so much to tell, so much to correct, and so much to bring to light. She is as tireless, passionate, and driven now as she was at the outset of her career. Her recent work—beginning with The People of the Kattawapiskak River (2012)—recounts present-day injustices faced by Indigenous people. The feature Trick or Treaty? (2014) examines significant discrepancies in how First Nations and the government of Canada see treaty obligations, and provides a remarkably clear overview of contemporary Indigenous social, cultural, and political aspirations.

Alanis Obomsawin’s body of work is more than a noteworthy set of numbers. To say she’s prolific is an understatement, in that it’s not quite an accurate way to characterize the fact that she’s created over 50 films, a rare feat for any filmmaker. What this body of work represents is a profound legacy, and one not unlike a prism. When one contemplates the entirety of her work, one can see how her films refract and reflect on so many aspects of our lives, our histories, and our aspirations. For more than five decades, Alanis Obomsawin has asserted an uncompromising, fierce, and unprecedented cinematic space for Indigenous perspectives, faces, and places.

Her voice—an essential part of her work—reverberates beyond her signature narration and takes root in your heart, mind, and spirit. Yes, she is a remarkable filmmaker with multiple honours and awards, each one richly deserved, and deserving of many more. Yes, she is one of Canada’s greatest filmmakers, and one of the world’s great documentarians. And yes, she is certainly La Grande Dame of global Indigenous cinema, beloved by the many she continues to inspire.

The term “living legend” fails to give her proper credit. She is a living embodiment of the truth that colonization has not beaten us, that the genocide Indigenous children endured did not eradicate our cultures, and that the hopes and dreams of Indigenous people can be realized.

And the truly astonishing thing is that she is still at it. She’s still making films, she’s still fighting, and she’s still inspiring—as any true force of nature does—fuelled by a determination to see a better world where Indigenous lives are respected. Through her activism, courage, and strength, her legacy continues to grow. Alanis Obomsawin, through her work, is a champion of justice. As an Indigenous person, one feels a deep sense of pride and affection for Alanis, but one also feels a great sense of protection from her. Her tireless fight, her endless passion, and her deep wells of love have protected us all. She may listen intently, but she also protects us.

The majority of the 50+ films directed by Alanis over a career spanning more than five decades at the NFB can be seen and explored here.

Jason Ryle is Anishinaabe from the Lake St. Martin First Nation in Manitoba, and currently lives in Toronto where he is the Executive Director of imagineNATIVE, an Indigenous-run media arts organisation. In addition to Jason’s work at imagineNATIVE, he is an independent programmer, writer, and producer. Since 2006, Jason has been a script reader for the Harold Greenberg Fund, which provides financial assistance to Canadian screenwriters. He also has several film projects in development including two narrative features, a dramatic series, and a documentary feature.

Featured image by Stephan Ballard