Gilles Groulx at 90 | Curator’s Perspective

Gilles Groulx at 90 | Curator’s Perspective

Filmmaker Gilles Groulx was born in the Saint-Henri borough of Montreal in 1931 and would have turned 90 on August 30. He died prematurely in August 1994 at the age of 63, leaving behind a body of work that was socially engaged, militant, revolutionary, subversive and demanding, but always grounded in reality, attentive to the concerns and hopes of workers, ordinary folks, the people.

Groulx occupies a crucial place in the landscape of Quebec cinema. His films—each of which reveals a desire to revitalize forms and genres, and offers an ardent, sometimes radical, perspective—are at the very foundation of Quebec cinema. Groulx’s work paved the way, revealing a potential path for the filmmakers who followed. The anniversary of his birthday is an opportunity to reflect on the significance of this director and his work.

From painting to cinema

Groulx came from a modest background, as one might guess from the neighbourhood in which he was born. Because of his talent for drawing, his family decided that he would be the one to get a higher education and become a commercial artist. He attended Collège Notre-Dame but didn’t finish his studies, and enrolled instead at the École des beaux-arts, where he came to know the painters Ulysse Comtois, Rita Letendre and Françoise Sullivan. While accompanying them on a trip to Saint-Hilaire, he met Paul-Émile Borduas, Claude Gauvreau and the other members of the Automatist group, signatories of the famous Refus global manifesto (1948). Thanks to Gauvreau, a cinephile, Groulx began to work with images and make short films using a Bolex camera he’d borrowed from his brother. He filmed Les héritiers (1955), which, although unfinished, is considered to be his first film. It already explored themes that would remain close to his heart: everyday life, the relationship between the individual and society, social inequalities, the consumer society.

His beginnings at the NFB

Groulx worked as an editor at Radio-Canada’s news service, where he developed his keen eye for images and his editing skills and technique. Then in 1956 he was hired by the NFB as an editor. He primarily edited short fiction films for television, including Panoramique (1957–1959), a series of 30-minute episodes on various aspects of Quebec society from the 1930s to the late 1950s. There would be Les mains nettes (1958) by Claude Jutra, a four-part film about the world of white-collar workers, Les 90 jours (1959) by Louis Portugais, a five-part story about strikes and workers’ struggles, and Il était une guerre (1959), also by Portugais, a five-part story about French Canadians and the Second World War. It was at this time that he worked with Michel Brault, Claude Jutra, Jean Roy, Guy Dufaux, Marcel Carrière, comrades who, with him and others, formed the core of the NFB’s French Unit—and with whom he would forever change the way documentaries are made.

Les raquetteurs

In 1958, Michel Brault was assigned to shoot a short report on a snowshoeing convention in Sherbrooke, Quebec. This was an opportunity for Groulx and his colleague to experiment with new film techniques by using lighter equipment. Accompanied by sound recordist Marcel Carrière, the two filmmakers captured images of the celebration on Friday and the snowshoe race the next day. When Grant McLean, the production manager, saw the footage, he thought it was unusable. Shaky camerawork, reflections on the imagery—this wasn’t how things were done at the NFB. The images were barely good enough to serve as stock footage! But Groulx objected and took the film to his editing suite, working on it in his spare time. He produced a 15-minute film. Supported by producers Tom Daly and Louis Portugais, Les raquetteurs was released that same year. This short by Brault and Groulx marked the birth of direct cinema at the NFB and set the French Unit apart. It led the way for a group of filmmakers who were evolving and wanted to be independent of the English management that governed production.

The French Unit and direct cinema

From 1958 to 1962, the French Unit connected around producers Fernand Dansereau, Louis Portugais, Bernard Devlin and Léonard Forest. Groulx and the other filmmakers in the Unit took the techniques and methods of direct cinema further, producing a series of experimental shorts for television. They gradually eliminated voiceover, stopped preparing interviews in advance, and always used a handheld camera. At the heart of the action, they captured sound live, simultaneously with the imagery, by using a portable tape recorder, thus shattering the hierarchical method of directing in favour of a versatile team of filmmakers. Creativity, discussion and learning were at the heart of the work environment, and everyone contributed to this new way of making cinema as they went along. During this period, Groulx made several outstanding short documentaries, including Golden Gloves (1961), Voir Miami (1962) and Un jeu si simple (1964), but, surprisingly, all of his experimentation culminated in a feature film.

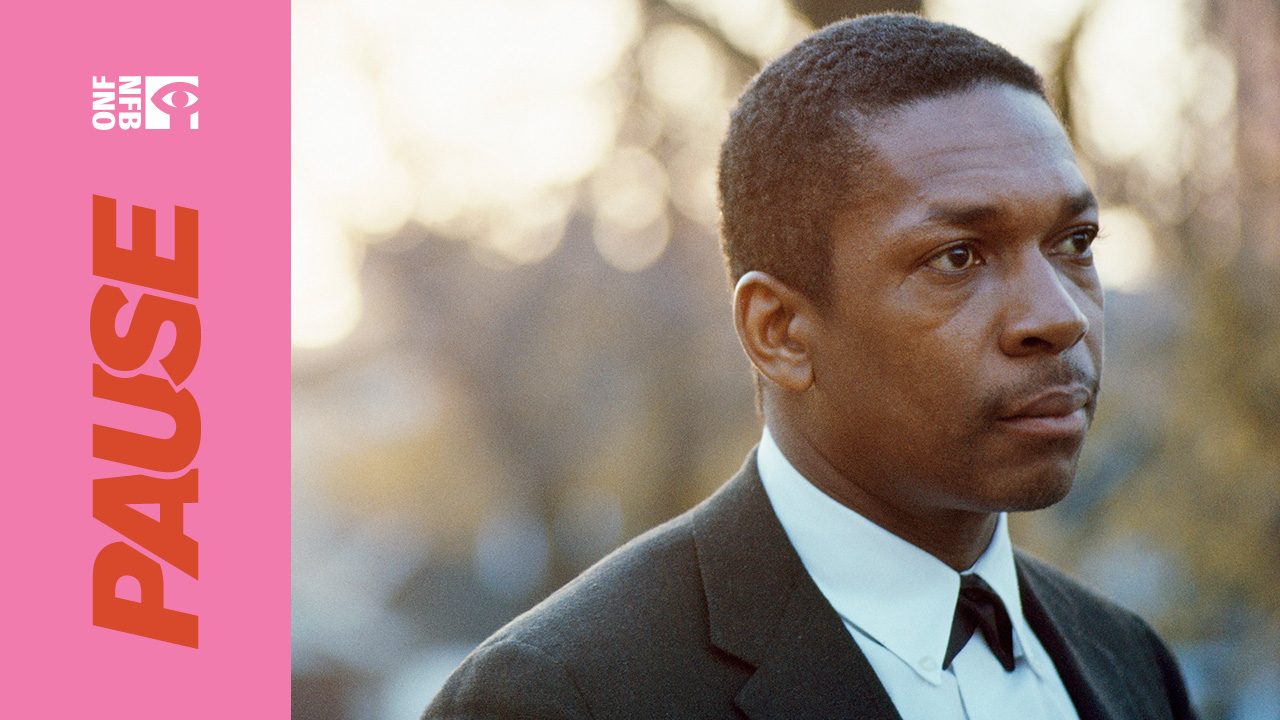

Golden Gloves, Gilles Groulx, provided by the National Film Board of Canada

Le chat dans le sac (The Cat in the Bag)

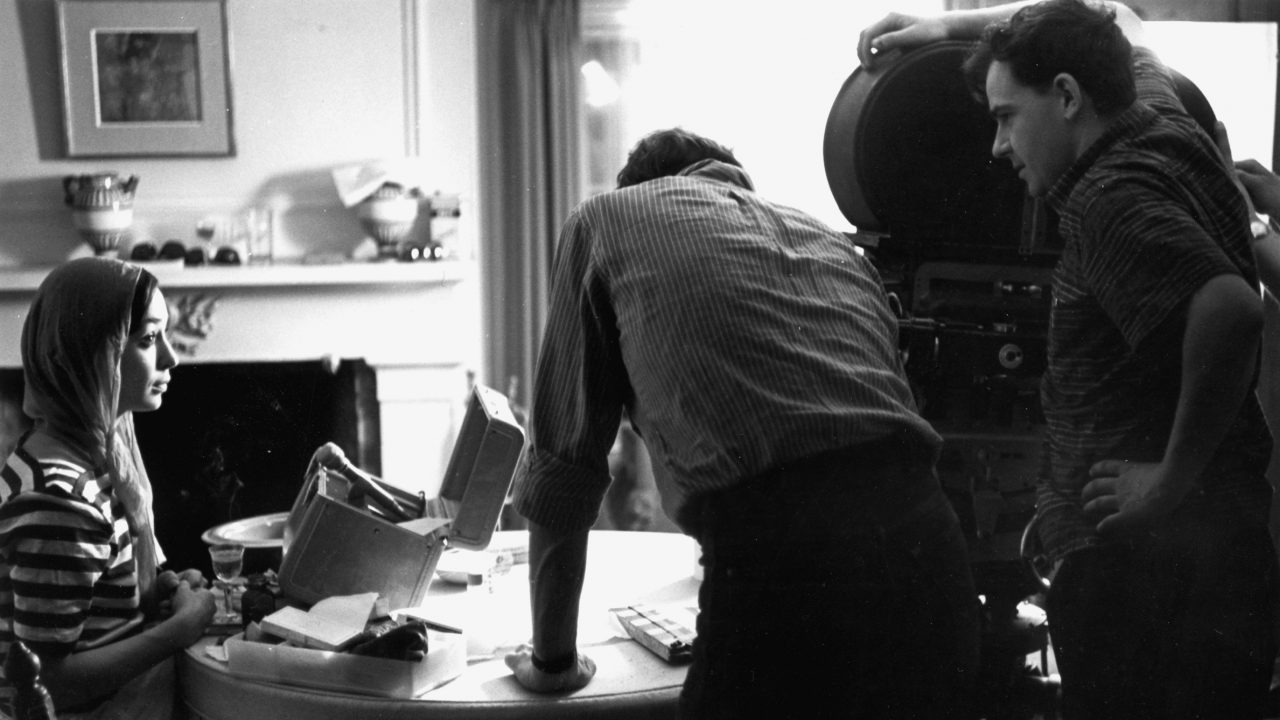

After making short documentaries, Groulx moved on to fiction. The film, which was originally intended to be part of a series of shorts about winter, was entitled Chronique d’une rupture. Backed by producer Jacques Bobet, Groulx made a feature instead and changed the title to Le chat dans le sac. Shot over 13 days on 35 mm, the film borrowed some direct cinema shooting methods and techniques, but Groulx had already rejected the direct cinema approach, which he found forced, preferring what he called spontaneous cinema. Although he worked from a script, he asked the actors to improvise their dialogue while shooting. He built the film around current events, used young, non-professional actors whose lives were similar to those of the characters, and developed a directing style that saw him sometimes intervening in scenes while the camera was still rolling.

Le chat dans le sac is a “film-miroir”—Groulx’s own term—an attempt to capture the lives of French Canadians, trapped in a society dominated by a mostly English-speaking ruling class, to spark an awakening and compel people to take action. With a couple’s breakup serving as metaphor for a future Quebec, Groulx’s first full-length film is thoroughly modern in its themes, its filming techniques and its soundtrack, which features pieces by American jazz legend John Coltrane. It’s unquestionably a seminal work of Quebec cinema.

The Cat in the Bag, Gilles Groulx, provided by the National Film Board of Canada

Subversive and revolutionary cinema

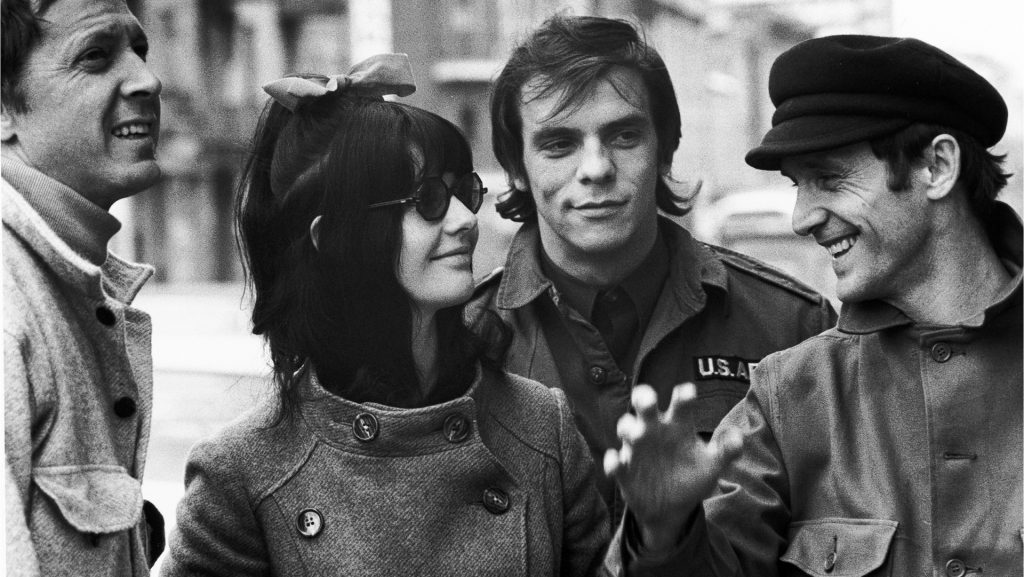

In April 1967, Groulx began shooting his second feature film, Où êtes-vous donc? (Where Are You?, 1969). What was to have been a reflection on singing performances in Quebec quickly became social criticism. The filmmaker condemns consumerism, which dehumanizes people and reduces their lives to three possibilities: to submit, like Mouffe’s character, to indulge, like Christian’s, or to resist, like Georges’. Où êtes-vous donc? offered viewers a new, fragmented form, combining intertitles, subtitles, narration, voiceovers, and images in both black and white and in colour.

In 1969, Groulx produced his third feature film, Entre tu et vous (Between You and You All), a sequence of seven tableaux depicting the breakup of a couple, victims of a consumer society and the channels used to convey its ideology: the media and advertising. If one hears “entretuez-vous” when pronouncing the title quickly, it’s because the “tu” and the “vous,” explained Groulx,[1] mean that the man in his film represses the woman, unconsciously or by abuse of power, just as Power oppresses the population, by abuse of trust or by abuse of power. The system promises us an extraordinary life, where to be happy is to consume. The guardian state pretends to protect its citizens, but in fact, it subjugates them by incarcerating them in a prison of consumption.

Between You and You All, Gilles Groulx, provided by the National Film Board of Canada

Like Groulx’s previous film, Entre tu et vous shatters the conventions of cinematic language. But it wasn’t simply about experimenting or doing something different. With these two films, Groulx wanted to challenge viewers, force them to react and wake them up from their state of lethargy and alienation, to awaken their conscience, to drive radical change, to overthrow the established order and reject conventional values.

24 heures ou plus (24 Hours or More)

In 1973, Groulx returned to documentaries with 24 heures ou plus. The title comes from the slogan adopted by the three major trade unions (CEQ, CSN, FTQ) during the 1972 general strike in Quebec. Filmed in November and December 1971, sometimes for 16 hours a day, it takes stock of the situation in Quebec to paint a portrait of daily life one year after the October Crisis. With the music of the Quebec rock band Offenbach playing in the background, Groulx and sociologist Jean-Marc Piotte comment on the film’s images, making a point of appearing on screen to show the viewer that the film’s perspective is subjective. Once again, Groulx wanted to make viewers question themselves. He wanted to raise awareness, to push for action, for revolution. The end of the film is unequivocal: the current system is incompatible with the essential needs of the population, and its makers call for the overthrow of the established order. NFB management saw this political denunciation as an act of sedition and asked Groulx to change the ending of the film. He refused. 24 heures ou plus was banned and not released until several years later.

24 Hours or More, Gilles Groulx, provided by the National Film Board of Canada

Au pays de Zom

After making Première question sur le bonheur (1977), a documentary about Mexican peasants struggling to reclaim their land, Groulx turned once more to fiction. The filmmaker again breathed new life into the form by making a film-opera, a story that was sung in its entirety by singer Joseph Rouleau, with music composed and directed by composer Jacques Hétu. Au pays de Zom (1982) features a rich, self-important and egocentric bourgeois financier who, in a long monologue, looks back on his life, successes and shortcomings, moving from his office overlooking the city to his luxurious home. A savage critique of the bourgeoisie and the powerful people all over this world who revel in wealth and their own self-satisfaction, Au pays de Zom would be Gilles Groulx’s last film.

He was seriously injured in a car accident, making it impossible for him to continue working. As Barbara Ulrich, his life partner and one of the actors in Le chat dans le sac, pointed out about his remaining years, “He’d spend 13 years of his life seeing everything he no longer was and everything he’d never be again…”[2]

The complete works of Gilles Groulx are now available free of charge on our site. I invite you to discover them by clicking here.

This post was originally written in French. Pour le lire en français, cliquez ici.

[1] See the article dated June 20, 1971, published in Québec-Presse (author is not credited).

[2] Voir Gilles Groulx (2002) by Denis Chouinard, National Board of Canada production.