The Man Who Wanted to Be an Animator: Claude Cloutier | Curator’s Perspective

The Man Who Wanted to Be an Animator: Claude Cloutier | Curator’s Perspective

To mark International Animation Day, October 28, nfb.ca is showcasing the latest film by Claude Cloutier, Bad Seeds (2020). The winner of the Audience Award in the international competition at the Sommets du cinéma d’animation de Montréal, as well as several other festival prizes in Calgary, New York and Los Angeles, this is the 14th short by the director, who first gained fame as a comic-strip artist and cartoonist in the early 1980s.

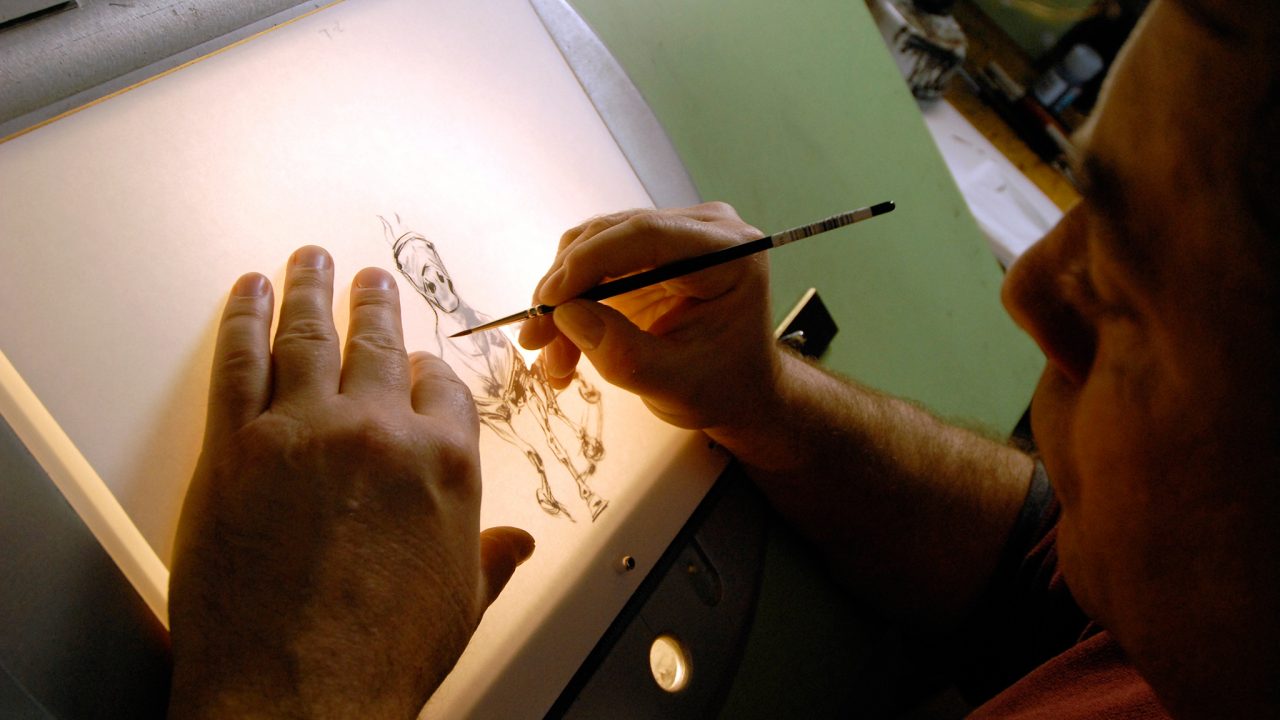

For this blog entry I’ll be looking back at the works of this hugely talented filmmaker, a virtuoso illustrator who uses a traditional animation technique—drawings on paper in India ink—but whose imagined worlds are anything but conventional. Cloutier is an exceptional artist, humble and reserved, who once told me he feels somewhat uncomfortable accepting accolades (regardless of the fact that they’re fully deserved!). He’s a man who, from a very early age, knew he wanted to be an animator.

The comic book artist

At the dawn of the 1980s, Claude Cloutier saw his first strip published in the Quebec satirical magazine Croc, under the title La légende des Jean-Guy. From 1982 to 1987, the now-defunct magazine’s readers followed these serialized misadventures of the denizens of an enchanted kingdom, all imagined by the artist. That realm, known today as Longueuil, was inhabited by a horde of oddball creatures, the Jean-Guys, who fed on naturally grown Kraft Dinners and whose two main pursuits were culture and sex. Other characters included bad guy Maurice Papineau, an unscrupulous businessman (not to mention the king of the realm), Gino the Extraterrestrial, Dieu Ouelet and Lucifer Proulx. The strip was an immediate hit, owing to the quality of the artwork and the absurdist humour that the young creator wove into his texts. Cloutier quickly found himself at the forefront of the Quebec bande dessinée scene, and La légende des Jean-Guy—published in a graphic noval album format in 1995 and reissued in 2015[1]—is now viewed by many as a classic. Cloutier also gave us the adventures of Gilles la Jungle, which first appeared in 1984 in the pages of Titanic magazine, and were also anthologized in a graphic novel an album a few years later.[2]

The animation filmmaker

Despite that success in print, the comix artist had other ambitions: he had always dreamed of becoming an animation filmmaker. The call eventually came from producer Yves Leduc of the NFB Animation Studio in 1986, who offered Cloutier the chance to direct a film adaptation of La légende des Jean-Guy. Cloutier enthusiastically agreed and began work on the project. Released as The Persistent Peddler (1988), it featured the Jean-Guys, of course, but also Dieu Ouelet, and Maurice Papineau as the titular hawker of umbrellas. The artist kept the same drawing style for his characters, but expanded the visual universe of his comic strip thanks to the possibilities that cinema provided. His film also eschewed dialogue, a practice that wound up being a constant in his work. The Persistent Peddler was selected to compete at the prestigious Cannes Festival, in the short film category. Cloutier’s career as a filmmaker was off and running!

The Persistent Peddler, Claude Cloutier, provided by the National Film Board of Canada

Children’s rights

In the early 1990s, Cloutier directed one of five trailers for the Ottawa International Animation Film Festival, as well as animated sequences in films by fellow directors from the NFB Animation Studio, including Jean-Jacques Leduc’s Mirrors of Time (1990) and Francine Desbiens’ To See the World (1992), before tackling his second film, Overdose (1994). This short was commissioned as part of the series Rights from the Heart, inspired by Article 31 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child. Though the subject this time was more serious—Cloutier was tasked with illustrating children’s right to rest and leisure—the film is bright, with a playful side and a sense of humour. Above all, though, the filmmaker managed to say a great deal in a short time (the film runs barely more than five minutes), and masterfully called out the fact that children in the modern era are overworked.

Overdose, Claude Cloutier, provided by the National Film Board of Canada

Science

In the late 1990s, the French Program Animation/Youth Studio began producing Science Please! (1998–2001), a series of 26 vignettes that explained scientific phenomena and discoveries in 60 seconds. Funny, lively and educational, the series deftly blended archival footage with animated sequences, was a huge success and proved a perfect match for Cloutier’s style. He wrote and animated several of the vignettes and directed five of them, including Slippery Ice! (1999) and The Internal Combustion Engine (2000).

Slippery Ice!, Claude Cloutier, provided by the National Film Board of Canada

While contributing to that series, Cloutier also began work on a more personal film, From the Big Bang to Tuesday Morning (2000). Though very different both in its tone and the drawing technique employed (a style and colours that recalled aquatint, a complex printmaking technique very similar to etching), it was in continuity with the 26 vignettes mentioned above, because it had science as its central theme. Here, Cloutier travelled hundreds of millions of years back in time to show the earliest forms of life on Earth and tell the story of humanity’s grand biological adventure. He depicted the evolution of sea creatures into land dwellers, dinosaurs, birds and primates, culminating in modern man who, inescapably, winds up stuck in a Tuesday morning traffic jam. The way the animals morph into each other is not unlike the imagery in Bad Seeds, made 20 years later. The richly evocative drawings, little touches of humour and poignant, solemn musical score by Pierre Desrochers, performed by the Ensemble cinématique, made this film a true hit.

From the Big Bang to Tuesday Morning, Claude Cloutier, provided by the National Film Board of Canada

Sleeping Betty, and success

In 2007, the filmmaker returned with an utterly unhinged adaptation of the Perrault fairy tale La Belle au bois dormant (Sleeping Beauty), retitled Isabelle au bois dormant (Sleeping Betty). This film saw him revive the offbeat mood and absurd humour of his comic-strip days, to the delight of audiences. We clearly sense that the filmmaker is enjoying himself, rediscovering the spirit—not to say the madness—of his earliest drawings. He takes the universe of fables and fairy tales and transforms it, caricatures it, with supreme humour and wit: his prince works at SOS Prince Inc. and rides a horse that’s more intent on goofing around for the camera than on helping rescue his master’s beloved; the princess’s palace looks more like a Plateau-Mont-Royal duplex; and a witch’s broom is hooked up to a vacuum cleaner. Cloutier also includes several nods to well-known figures and art works: John Wayne, Sigmund Freud, Prince Charles (now King Charles III, of course), the Mona Lisa, Picasso paintings, the Easter Island statues and even Bonhomme Carnaval. And he embeds various amusing details into his drawings (frames on the walls, utility poles, road signs, trees). In short, everything is designed—in the sense of drawn—to make us laugh. Sleeping Betty was a massive success, garnering over 20 awards, including Best Animated Short Film at the 10th Jutra Awards in 2007, and remains one of the most-viewed films on nfb.ca and onf.ca.

Sleeping Betty, Claude Cloutier, provided by the National Film Board of Canada

In the trenches of the Great War

Cloutier’s next film would be in an entirely different register. The Trenches (2010) was a more sombre and serious work. Inspired by the experiences of his grandfather, who saw combat, he leads us into the trenches of World War I, from which, far too often, the only way out was death. Through the eyes of a young soldier, he brings us face to face with the pure horror of battle. To infuse his imagery with greater realism, Cloutier used rotoscoping, the animation technique that involves transforming previously shot live-action images into animation. To do so, the animator places a sheet of paper onto a projected frame of film and traces its outlines. For this film, Cloutier used archival footage of the Great War, shot between 1916 and 1918 and carefully preserved in the NFB’s conservation vaults. The result was striking. The Trenches is a powerful and unsettling film.

The Trenches, Claude Cloutier, provided by the National Film Board of Canada

Que sera, sera

Cloutier’s next film was Interférence (2014), a short made outside the NFB as part of the series Libérez Jafar Panahi, in support of the Iranian filmmaker imprisoned in his own country. He resumed his collaboration with the NFB with Carface (2015), a critique of all-powerful Big Oil, our fascination with gas-guzzling vehicles and our indifference to the dangers posed to our planet by automotive pollution. In a style that harks back to the golden age of Hollywood musicals, anthropomorphized massive American sedans of the 1950s sing “Que sera, sera / Whatever will be, will be / The future’s not ours to see / Que sera, sera.” Here, Cloutier uses satire to great effect to raise awareness.

Carface, Claude Cloutier, provided by the National Film Board of Canada

And what can I say about his latest film? For now, nothing! I don’t want to spoil your fun in discovering it on nfb.ca.

A leading light of Quebec comics and cartoons in the 1980s, Claude Cloutier rapidly became a key figure in animation in the ensuing years. His body of animated work comprises 14 films, if we include the trailer he made for the 1990 Ottawa International Animation Film Festival. He has worked at the French Program Animation Studio for more than 35 years, where he is also a mentor for young filmmakers.

You can explore almost all of his films here.

[1]. Cloutier, Claude. La légende des Jean-Guy, Montreal: La Pastèque, 2015.

[2]. Cloutier, Claude. Gilles la Jungle, Montreal: La Pastèque, 2014.