Treaty Education through NFB Films

Treaty Education through NFB Films

Treaty Education through NFB Films: “As Long as the Sun Shines, the Grass Grows, and the Waters Flow”

Strong friendships and relationships don’t just happen. They’re the result of building understanding over time, negotiating boundaries and coming to agreements. A Treaty is an example of this. Living on this land means we’re all connected to the layered Treaties and relationships of this place. We’re all Treaty people and we should take the time to think about our relationship and responsibilities to Treaties.

History of Treaties

Treaties and Treaty-making was and is an integral part of Indigenous culture. Treaties were mostly oral agreements made between sovereign nations. They centred on trade, passage through ancestral lands and peace, as well as familial and kinship relationships. Treaties were ratified with ceremony, feasting and protocols. They were renewed annually and viewed as sacred covenants.

Ratified by chiefs, headmen and Elders, Treaty-making was a community enterprise that included women, extended families and spiritual leaders. Treaties were viewed as tripartite agreements between the two Treaty-making partners and the Creator.

First Nations in eastern Canada recorded the terms of Treaty agreements on wampum belts. In western Canada, Elders and Knowledge Keepers were tasked with the venerable job of remembering the terms of Treaty. In some cases, Treaty-making was recorded by First Nations on paper. Examples of this are the Peguis Selkirk Treaty (1817), the Paypom Document (1873) and the pictograph of the Treaty 4 (1874) negotiations illustrated by Chief Paskwa.

Treaties with European Newcomers

When European newcomers came to what is now Canada, Treaty-making continued. Beginning in 1701, the British colonies of North America (which at that time included parts of what is now Canada and the United States), and the British Crown entered into Treaties with Indigenous nations. These agreements were centred on peace, economic relations and military alliances.

Prior to Confederation, several Treaties were made between the British Crown and First Nations. These include the Treaties of Peace and Neutrality (1701–1760), the Peace and Friendship Treaties (1725–1779), Upper Canada Land Surrenders and the Williams Treaties (1764–1862/1923), and the Robinson Treaties and Douglas Treaties (1850–1854).

Indigenous Perspectives

From an Indigenous perspective, Treaty-making with the Crown formalized and made sacred the relationship with European newcomers, set parameters for sharing and honouring the land and waters and enacted First Nations’ agency and foresight in regard to cultural and economic survival.

In many ways, the fur trade became an ad hoc Treaty relationship. Traders, trappers, Baymen, voyageurs and other fur traders interacted with First Nations based on reciprocity and good relations. There were many economic benefits that came to the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) and its employees through the several post-Confederation Treaties made at or near HBC forts.

Historical Context of Treaty-Making

The backdrop to these historical Treaties included the Seven Years War (1757–1763), fought in North America between the French and British, the American Revolution (1775–1783), the War of 1812 (1812–1815) and the American Civil War (1861–1865). These conflicts took place on traditional Indigenous territories across the continent, imposed colonial borders and restrictions on the land and affected the relationship among Indigenous people as well as between First Nations and the Crown—whether the Crown was represented by British colonial powers or the Canadian government.

First Nations acted as allies to the French, British, American and Canadian governments at different times and in varying capacities.

After the Seven Years War, the British passed the Royal Proclamation (1763). One-third of the proclamation’s text was dedicated to Indigenous peoples; notably, the Treaty-making process was formalized. Newcomers and settlers could not access Indigenous lands without a Treaty. A substantial part of the land west of the Appalachian Mountains was “reserved” for “Indians.”

Britain and the United States signed the Jay Treaty in 1794 to resolve tensions remaining following the American Revolution. The Treaty recognized that: “Indians dwelling on either side of the … boundary line … [shall have the right] freely to pass and repass by land or island navigation … and to navigate all the lakes, rivers and waters thereof, freely, to carry on trade and commerce with each other.” Canada and the United States have implemented (or not) the Jay Treaty to varying degrees.

During the War of 1812, the Dakota Nation pledged their allegiance to Britain, in return for oaths of perpetual obligation. After the war, the British issued “King George III medals” to Indigenous warriors as an act of gratitude and recognition of their support of the Crown during the war against the Americans.

After the Indian Wars in the United States and the Battle of Little Big Horn in 1876, many Dakota fled the United States for their northern territory in southern Manitoba and Saskatchewan. The promise of “perpetual obligation” was broken by the Crown. The Dakota did not enter into Treaty agreements with Canada.

The Numbered Treaties

Treaty-making continued in the west and north of Canada after Confederation in 1867, opening up large areas of land occupied by First Nations to the Crown in exchange for reserve lands and other provisions. The Numbered Treaties, consisting of eleven Treaties spanning western and northern Canada, were negotiated between 1871–1921.

By 1871, the Canadian government had purchased Rupert’s Land from the Hudson’s Bay Company, quelled the Red River Resistance and added Manitoba as the fifth province. It had convinced British Columbia to join Confederation with the promise of a transcontinental railway and began advertising “free land” for European immigrants, thus far preventing American “Manifest Destiny”—the unquestioned assumption that the United States would continue its territorial expansion—from annexing western Canada.

First Nations at the time saw the Numbered Treaties as their equitable entry into the new Confederation. Treaties were intended to secure a transition to new economies as well as safeguard culture, language and traditions. Treaties were meant to share the land with newcomers and set out rights and obligations for both Treaty partners.

The Numbered Treaties are recorded as written, legal documents that reflect the government’s understanding. However, it’s important to note that concepts such as “cede,” “surrender” and “yield up” are not part of Indigenous worldviews. First Nations’ perspectives on the spirit and intent of Treaties are revealed in oral histories, relationships with Creation, and First Nations’ languages.

Trick or Treaty?, Alanis Obomsawin, provided by the National Film Board of Canada

Modern-Day Treaties

Not all Treaties took place in the distant past. The 1975 James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement, the 1993 Nunavut Treaty and the 1998 British Columbia Nisga’a land-claim settlement are all examples of modern-day Treaties.

Modern-day Treaties came about in areas of Canada where Indigenous land rights had not been resolved by Treaty. They were negotiated between Indigenous nations, Canada and the province or territory in which they are located.

Like historic treaties, modern-day Treaties set out the rights and responsibilities of the Treaty partners, including provisions, and are part of Canadian law.

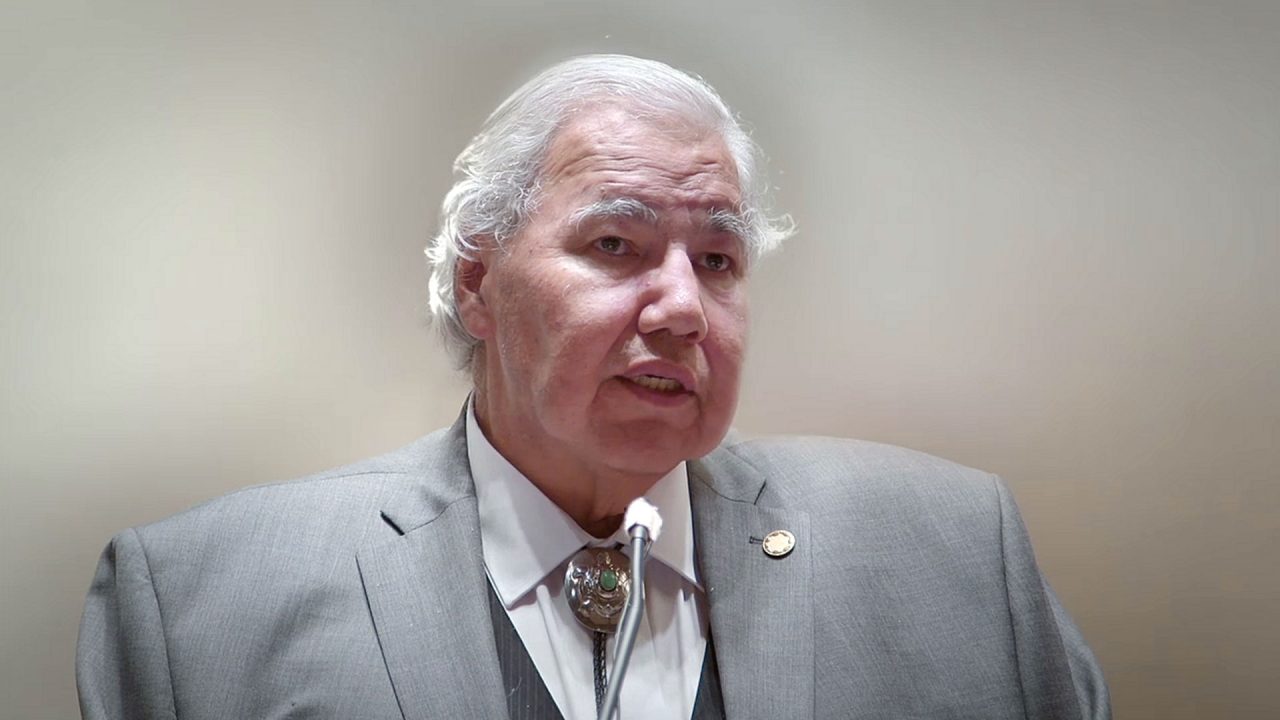

You Are on Indian Land, Michael Kanentakeron Mitchell, provided by the National Film Board of Canada

Treaty Relationships Today

The Crown/Canadian government has not always been a worthy Treaty partner. Treaty promises have been neglected, ignored and broken. Bilateral (or trilateral if the Creator is included) Treaty agreements have been usurped, waylaid and undone by the unilateral Indian Act.

Treaties are not a relic of Canada’s past. They remain a part of our contemporary society. They help define the relationship between First Nations and the Crown, and between First Nations and other Canadians, and act as a guidepost for current movements toward reconciliation. The Treaty relationship is evergreen: “as long as the sun shines, the grass grows, and the waters flow.”

Resources:

Learn more about the Indian Act

Connie Wyatt-Anderson is an educator from The Pas, Manitoba. She taught high school History and Geography on the adjacent Opaskwayak Cree Nation for 22 years, leaving in 2014 to focus on pedagogical writing. She has been involved in the creation of student learning materials and curricula at the provincial, national and international level, and has contributed to a number of textbooks, teacher support guides and school publications, including co-authorship of the Grade 11 Canadian history textbook currently used in Manitoba schools. Connie co-wrote and designed Manitoba’s Treaty Education Initiative and continues to train teachers and school leaders as Treaty Education Lead.

Pour lire cet article en français, cliquez ici.

Discover more Educational blog posts | Watch educational films on NFB Education | Watch educational playlists on NFB Education | Follow NFB Education on Facebook | Follow NFB Education on Pinterest | Subscribe to the NFB Education Newsletter