The Deeper They Bury Me | No Exit?

The Deeper They Bury Me | No Exit?

This post was written by The Centre of Research, Policy & Program Development at the John Howard Society of Ontario. The Centre engages in research which contributes to the evidence-based literature in the criminal and social justice fields, policy analysis and rigorous program evaluation.

No Exit?

Wait! You’ll see how simple it is. Childishly simple. Obviously there aren’t any physical torments-you agree don’t you? And yet we’re in hell. And no one else will come here […] In short, there’s someone absent here, the official torturer. – Inez in Jean-Paul Sartre’s play, No Exit.

In Sartre’s famous play No Exit, three souls condemned to hell unveil how anguish and torment can operate in mundane and subtle settings. Cruel and unusual punishment is not limited to a frightening torturer wielding grotesque instruments. The mind can be tormented through a simple combination of isolation and time.

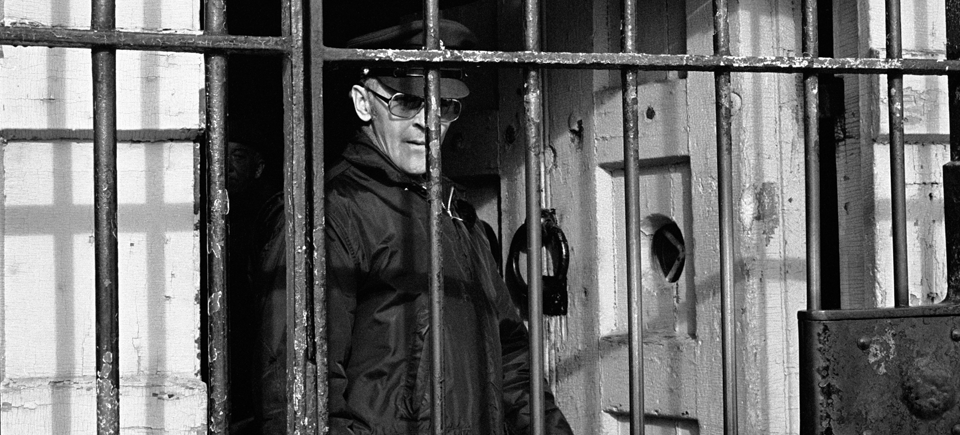

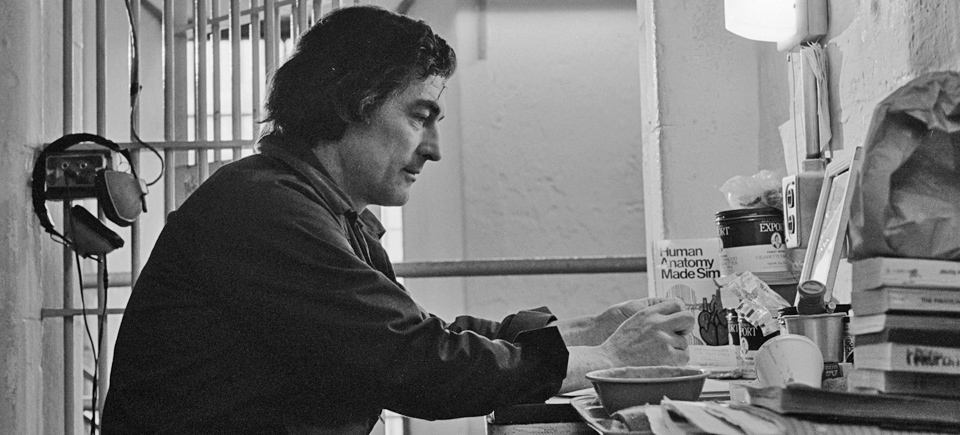

The story of Herman’s decades-long solitary confinement, powerfully displayed in The Deeper They Bury Me, is both shocking and moving. His ability to direct his focus on matters outside of his confinement, in spite of his surroundings, is a testament to his incredible strength.

The mental fortitude and clarity Herman displays is the exception rather than the rule for a prisoner who has endured prolonged periods of solitary confinement. For most prisoners, the experience of solitary confinement, or ‘segregation’ as it is typically referred to in correctional contexts, is psychologically and emotionally damaging even in short doses.

What does isolation in prison do to the mind?

Humans are social beings. Research has shown prolonged periods of isolation to cause a variety of negative physical and mental health effects. Hallucination, cognitive disabilities, insomnia, self-mutilation, paranoia, and suicidal tendencies are only some of the reported effects of prolonged segregation. Segregation is especially damaging for those with pre-existing mental health issues as it can aggravate or lead to other psychiatric symptoms.

Similar to Sartre’s hell, there is no official torturer in segregation. Instead, it is the absence of social contact and cognitive stimuli that tortures the mind.

What’s happening in Canada?

Over-relying on the use of segregation is a nationwide problem in Canada. To paint a more detailed picture of how segregation is used in Canada, this post will use provincial jails in Ontario as a case study.

Provincial jails house prisoners serving less than two years in custody or those on remand – that is, persons awaiting their bail hearing or trial and who are in large part still legally innocent.

Last year approximately 61,000 prisoners were admitted to provincial jails in Ontario. Over 60% of prisoners in our provincial jails are on remand, and in most instances (70%) the most serious charge they are facing is non-violent.

Studies suggest that the experience of segregation may be worse for remanded populations compared to sentenced populations, which is unsettling given Ontario’s high remand rate. The debilitating uncertainty around the outcome of one’s case; having to cope with the shock of transitioning from freedom to incarceration; these are but a few factors that contribute to the higher incidence of suicide and self-harm – almost always while in segregation – among remanded populations.

Segregation in jails is not experienced as a simple ‘timeout’ from the general population: prisoners are locked alone in their cells for 23 hours a day without programing or privileges. They are fed through a slot in their door.

Recently in Ontario, Jamie Simpson’s story details how segregation can be accompanied with other forms of punishment. Being withheld from showers and mattresses during the day, leaving only the metal bunk or cold concrete floor to sit on, are some of the punitive elements which can be combined with isolation. One of the most trying aspects of segregation, in both Jamie and Herman’s cases, is its at times indefinite nature – not knowing if or when you are getting out.

Why do we isolate?

Broadly speaking segregation is used to maintain the security of the institution or to discipline misconduct. However, recent trends in Ontario suggest there are other factors contributing to the use of segregation.

Currently a significant number of segregation admissions are due to overcrowding and population management efforts. Ontario is increasingly utilizing segregation as a means of managing a growing influx of prisoners with physical and mental health concerns.

The current situation in Ontario is predominantly a crisis of circumstance rather than choice. Appropriate physical and mental health facilities are often not available in provincial jails. A large number of individuals are remanded on non-violent charges leading to overcrowding. Overcrowding in turn escalates tensions both among prisoners and between prisoners and correctional officers, making the environment less safe for all. Correctional staff are often left with no options but to repurpose segregation units as auxiliary correctional beds.

Is there an exit?

Unlike Sartre’s hell, there is an exit in the form of promising policy options. Recently Ontario’s Ministry of Community Safety and Correctional Services announced it is launching a review of its policy on segregation. Reviewing the current policy around the use of segregation is a critical first step.

We would also suggest addressing the issues that give rise to the misuse of segregation in prison necessitates providing solutions outside of prison. Alternatives to pre-trial detention and a re-evaluation of our bail courts must be explored in Ontario to reduce overcrowding. Providing much needed stable housing and mental health treatment outside of jails would help stop the revolving door of marginalized individuals entering and exiting the criminal justice system.

If darkness cannot drive out darkness, then departing from our current segregation practices requires shifting towards more humane policies in the criminal justice system and corrections.