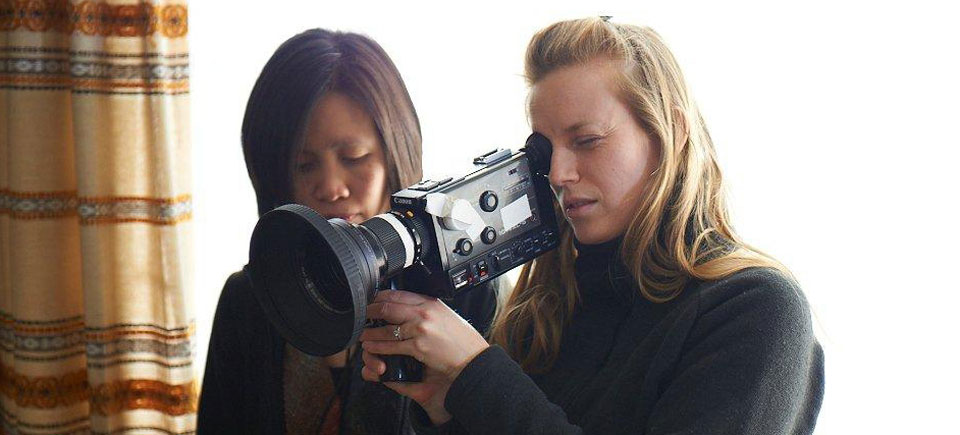

Q&A with Carrie Haber, Part 2

This is Part 2 of my interview with writer, filmmaker, editor and composer Carrie Haber. You can read Part 1 here.

Julie Matlin: On average, how many projects are you involved with each year?

Carrie Haber: Hard to think of this in terms of quantity, because of course it depends on the scale of the project. I can’t speak to averages, either.

This year I worked on over twenty projects. I directed a 22-minute documentary, composed a 17-minute score for CBC, recorded an album, edited three other short films, gave workshops, was editing consultant to a few projects and wrote about twenty magazine articles.

But when I was working on my feature, I spent the entire year on it. When the work is contractually binding, I’m not free to take on other projects, so it all depends. But I love the variety of the work, and I do as much as I can.

JM: When you work as an editor, do you often work closely with the director or do you do the bulk of the creative decision-making?

CH: This really depends on the relationship with the director, but after some initial work around the themes and goals of the project, I generally like to work as an autonomous editor until I have a first assembly, and have meted out what I see as the raw material and the other possible storylines.

I think it’s so important for directors to bring editors into the process early on, because the raw footage is so often different from what the director has taken away from the experience of ‘having been there’.

Memory corrupts. There is the emotional attachment to footage, which is why I think distance is important for a director to take between shooting and post. For instance, having felt anxious while shooting a particular scene can colour a director’s expectations of that footage. The editor only sees what has been captured, and can be more objective about the value of the footage to further the exploration of the film’s subject.

I love the collaborative nature of filmmaking, and all the delicious discussion that arises around arriving at an assembly, but I also appreciate the long periods of quiet, the almost subconscious act of cutting, of responding to rhythm and shot composition, eyelines, etc. That flow can be difficult to achieve while engaged in the more conscious act of conversational decision-making.

I had a great relationship with Shira Avni while working on Tying Your Own Shoes, in which there was a lot of mutual respect and plenty of space for each of us to work and make creative decisions.

JM: Can you elaborate a little on the workshops you give?

CH: I’ve given a few about editing and story structure, character development, and one about different narrative styles of documentary (e.g. cinema verité, docufiction, cinema direct, reflexive cinema, docudrama, etc.), their techniques and effectiveness in socio-political documentary filmmaking.

I have also given workshops in how to use Final Cut Pro for animators and emerging documentary filmmakers. Sometimes I talk about how the brain edits life, and how we model from this phenomenon in making film editing choices.

JM: Your bio also mentions some work in the non-profit sector. The NFB is all about social change through filmmaking. What is your take on this?

CH: I think it’s one of the most effective catalysts, because when well executed, a film is actually a tactile experience, and becomes internalized into the psyche. This is the place where change happens – those parts of the brain in which our belief systems are nurtured.

Film doesn’t make direct demands on behaviours, as do policy shifts or regulations. It doesn’t feed the poor. It is not the job of documentary to present solutions to the cases it studies, that’s more a lawyer’s job.

But cinema can host empathy and understanding, and connect populations that would otherwise be alienated from each another. Film accesses our attitudes, and transports us through an ever-evolving present moment, and this is a powerful transformative experience that we totally take for granted now, but in terms of human evolution is a unique experience.

JM: What advice do you have for people who are looking to get into the industry?

CH: Go make a film. Beg and barter, make expensive mistakes, embarrass yourself, find equipment, call in favours. It’s a totally foolish thing to do, but I still believe it’s way better than waiting for somebody else to give you opportunities. That’s even more foolish.