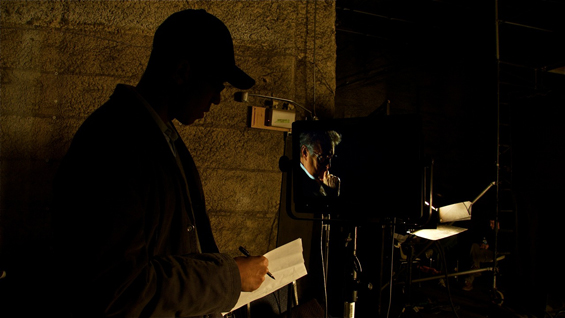

Filmmaker Hubert Davis talks about Robin Phillips and the making of Move Your Mind

Filmmaker Hubert Davis talks about Robin Phillips and the making of Move Your Mind

Move Your Mind, Hubert Davis, provided by the National Film Board of Canada

Hubert Davis is an Oscar-nominated filmmaker based in Toronto. He made his directorial debut with Hardwood, a tribute to his father, former Harlem Globetrotter Mel Davis. He went on to direct Invisible City, a coming-of-age story shot in Regent Park (Toronto’s inner-city housing project), which won Best Canadian Feature at Hot Docs.

Most recently, Davis made a short film about theatre director Robin Phillips as part of the NFB’s partnership with the Governor General’s Performing Arts Awards. Honouring the best in Canadian theatre, dance, classical music, popular music, film, radio and TV broadcasting, these awards have been accompanied, for the past several years, by short NFB films commemorating the winners.

Davis’ resulting film, Move Your Mind, is being launched on NFB.ca today. I recently spoke to Davis on the phone and asked him to tell me about making this short documentary, the creative process behind it, and whether he ever worries about losing his street cred. Here is some of what he answered.

Carolyne Weldon: To someone not familiar with Robin Phillips and his work, how would you describe him/introduce him?

Hubert Davis: Robin Phillips is a bit of a legend. Not only in Canadian theatre communities, but also in the international theatre community at large. He’s renowned for the outstanding work he’s done with some of the most famous and talented actors of our day. He’s also known for contributing to the arts, being a champion of the arts. He’s someone who’s always supported the work of artists and affirmed the necessity of art in society. And he’s a very forward thinker as well. He just received this Lifetime Artistic Achievement in theatre, but it doesn’t mean he will be folding his arms and calling it a day anytime soon. He keeps going.

CW: How did this film project come about?

HD: It was through the NFB in Toronto, Gerry Flahive and Lea Marin. Gerry had contacted me a few years ago for another similar Governor General film and I’d turned it down because I was crazy busy with other projects at the time. But I regretted it. It was something Gerry said that made me regret not doing it, actually. He said, “Don’t think about it as a profile, think about it as an opportunity to do whatever film you want.” Four minutes, total freedom.

CW: Did you have any awareness of Phillips’s work prior to being asked to make a film about him? Had you seen any of his plays?

HD: I hadn’t. I was totally fresh to it. But I was totally happy to have gotten him – it was a good fit. It was like a gift for me. He inspired me on many levels, like even professionally, in my own work as a filmmaker. You know he’s someone who’s known to do wonders with difficult actors. He gets flown into sets where nothing is working anymore and he comes in and saves the day…

CW: Like an “actor whisperer”…

HD: (Laughs) Yeah! I mean, talking to him made me feel like I was on the right path, in a way. It was really positive and affirming. Maybe it felt that way because of the contrast with a lot of the work I do, where a lot of times things are more negative… making films is hard, and being an independent filmmaker in Canada is hard, and so on and so forth….

We spoke on the phone, first, and then I sat down with him. It was a highlight of my year. Prior to meeting him, I’d read all kinds about him and didn’t know what to expect. Things about the eccentricities, the perfectionism…

CW: What do you mean?

HD: Well, he’s a perfectionist. He’s not a person to make everything easy. Which, in our day and age can be interpreted as somewhat of a diva thing. It was just the opposite of that when we met. He was so gracious. He said he trusted me for the film, that he was putting all of his faith in my hands.

CW: How did you come up with the creative concept for the film?

HD: Well what I wanted to was get the audio down first. I think as an editor. That’s my background. So we did this 2-hour interview, out of which I was supposed to extract 4 minutes. I ended up with 12 minutes. I thought, how am I going to boil that down to 4? All of it was so pertinent and on point. But it had to be done.

For the visuals I wanted to use this Phantom Camera, which shoots 1000 frames per second. I had the idea of showing all the objects associated to his art: the actors, the props, the sets, the words on the page, all in a very abstract way. To visually show people. And I wanted it to be in movement, because it is always in motion, in constant progress. His work never rests.

CW: This is a very different sort of topic for you, no? After Hardwood and Invisible City?

HD: Making Move Your Mind was really interesting for me. I enjoyed getting to deconstruct an artist’s work. I enjoy learning that sort of stuff for my own good, sort of. “How does it work?” “What is the artist’s process?” In a cliché way, it helps broaden my horizons, if you will. Same thing for this new project I’m working on with the NFB, about a man who’s been commissioned to paint a portrait of the Queen. I know nothing about that – painting I mean. But these projects enable me to understand art better. And that’s great.

CW: Are you ever concerned these more institutional sorts of projects diminish grit, your “streetness”?

HD: Nah. I’ve always hoped to be able to balance both, to fill the gaps between 2 things. You see the same time as I’m working on the Queen Jubilee project I’m also writing a screenplay based on some of the same characters from Invisible City. It’s a fiction project based in social housing projects in Toronto. I like being able to go back and forth.

Hubert – a very artful execution of thought provoking material. Nicely done!

I met Robin Phillips in summer 1971 in Chichester, where he was directing Caesar and Cleopatra with John Clement and Anna Calder-Marshall. I was visiting a friend who was working in wardrobe and Phillips came in asking us to sing him nursery rhymes; he wanted Cleopatra to be singing one when Caesar came upon her.

I re-met him in Vancouver in ’82 when Phillips was playing in The Dresser at the Vancouver Playhouse. I was the subject (with Phillips) of a newspaper interview; I had dressed Tom Courtney (who played The Dresser in film) when I had worked years before in London, and the writer saw synchronicity there and set up the article.

Three years later, I was the theatre critic at that same newspaper, The Province, yet I never forgot my initial meeting with Phillips, his lack of self-celebrity, his commitment to giving his actor every detail to create her character. I learned to look at a director’s work through that short but perfect experience.