Max Ward: The NFB Profiles a Canadian Aviation Legend

Max Ward: The NFB Profiles a Canadian Aviation Legend

Do you remember Wardair? It was a very prominent Canadian airline in the 1970s and 1980s. We have recently added a documentary about the airline’s founder, Max Ward, to NFB.ca, and I thought it would be a great time to write a post about it.

I’m going to do something a little different this time. Instead of only talking about the film’s production and distribution, I’m going to go full aviation geek on you and talk about the aviation side of things.

History of the airline

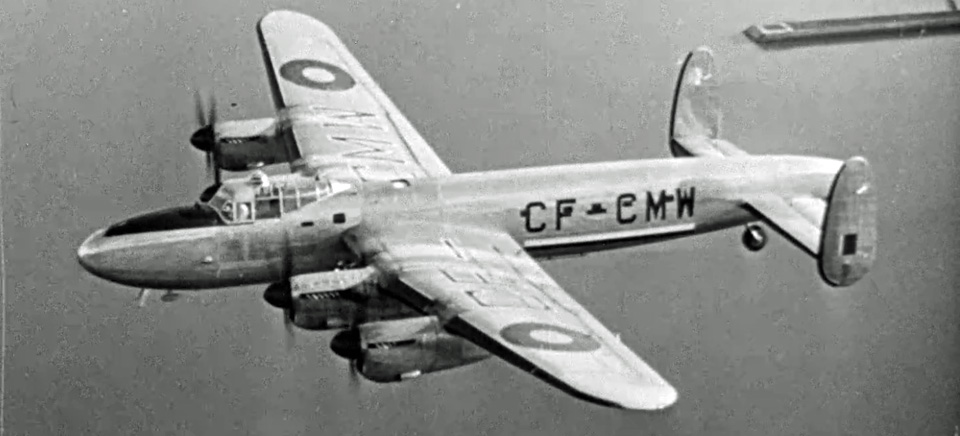

First, a little history: Wardair was founded by bush pilot Max Ward in 1953. The airline originally served the Canadian North as an air charter business but then expanded, becoming an air holiday charter operator in 1962. In the 1970s and 1980s it was (briefly) Canada’s third largest airline, despite the fact that it only operated seven jets. In the mid 1980s, the airline switched to scheduled services and never recovered. Ward eventually sold the company to Canadian Airlines in 1989, ending one of the most fascinating airline stories ever. (Fun fact: Wardair was the first airline in Canada to operate a Boeing jet, the 727, bought in 1966.)

The documentary

The documentary Max Ward was filmed in 1983–84, when Wardair was just about to make the leap into the big leagues. Sadly, this change also led to its demise. In the documentary, we are told that Wardair is a major player in the sun holiday charters to such places as Hawaii and Barbados, but is looking to take the step up to scheduled services. Max Ward is shown throughout the film managing his company with one basic philosophy: give the customer the best possible service for the best possible price. Ward is a hands-on type of president, personally inspecting all aspects of his operation. He is shown on board aircraft noting things that need to be corrected and fixed, no matter how small or insignificant they might seem.

It is fascinating to see the succulent meals served during the Wardair flights—on Royal Doulton china! Ward explains that he prefers to eat on good crockery and his passengers deserve the same. Serving meals on such good china also makes excellent business sense as they are much tougher to break and last a great deal longer. How times have changed!

Distributing the film

When the film was finished, it was sent to the CBC, who promptly rejected it. They felt it was a 50-minute commercial for Wardair and decided not to purchase it. CTV also rejected the film. The NFB had a hard time selling Max Ward but eventually did, to individual television stations CFPL London (Ontario), CKX Brandon (Manitoba) and CFCN Calgary. International sales were just as disappointing, with only an Australian distributor buying the rights for the educational market in that country.

The lack of sales is not surprising. The film was made at the wrong time (in my opinion). Wardair was about to become a major player in Canada’s aviation industry, albeit for a brief time only. At the time of filming it was just a small airline with a great deal of potential. The paradox is that the switch to scheduled services was what started the airline’s downfall. There is a telling moment in the film when the filmmakers ask some travellers why they chose Wardair. The answer is not surprising: Wardair offers the cheapest flights. Unfortunately, the bottom line is always what makes or breaks any business. Competing with the major airlines of the day, Air Canada and CP Air, was not going to be easy, even with meals served on Royal Doulton china.

The most interesting aspect of this film is Ward. I think the film should have focused more on his days as an aviation pioneer in Northern Canada and less on his appearance in front of a panel for airline de-regulation. His position is clear and does not need to be repeated. Even with these flaws, the film is still fascinating, especially when you realize just how much the airline industry has changed since then. It remains a time capsule of a different era in Canadian aviation.

I invite you to watch Max Ward even if you are not an aviation enthusiast. It chronicles the adventures of a small Canadian company that dared to dream big and its dedicated president, who wanted to give customers the best flying experience possible.

Aviation geeks please note that Wardair’s fleet of four Boeing 747s are prominently featured in the film, in flight and on the ground (especially C-GXRD). Throughout the film we also catch a quick glimpse of several other aircraft. I was pretty excited to see a Quebecair BAC-1-11 landing at Trudeau Airport (20 seconds into the film) as well as a CP Air DC-10, resplendent in its bright orange livery. Be sure to stay tuned until the end to see one of Wardair’s DC-10s taking off from Pearson.

Enjoy the film.

Max Ward, William Canning, provided by the National Film Board of Canada

Thanks for giving an Excellent Blog in Aviation, it’s very useful information to us, I learned new info about the aviation industry, keep on it doing like this, I waiting for your updates, Thank you So much…

I was hired to teach in Yellowknife in 1958 by the Catholic school board (I believe it was the only Board in the NWT at that time as all other schools were run by the federal government’s Northern and Indian Affairs Department). I was offered a room in the mine recorder’s office, the basement of which had been divided into smallish rooms to accommodate the pilots and prospectors hired by Max Ward to prospect for gold and uranium further north.

My room happened to be right next to Max Ward’s. Although Max lived in Edmonton, he occasionally bunked in next door when he was ferrying prospectors into the tundra.

At that time he was flying bush planes from the harbour in the old town. They were pontoon -equipped Beaver and Otter Dehavilland.

Often when Max was in town he would come into my room and sit on the edge of the bed (no chairs)

and tell me about some interesting venture he had just been on. He was a really easygoing I personable,modest character and very ready to listen to what it was like teaching in the north.

He told me of his plans to start a commercial passenger service as he didn’t need the hassle of being a bush pilot.

I don’t know what year Wardair was established but it was soon thereafter.

Greetings from Lahti. Finland. This video is an excellent introduction into apparently how to manage an airline cost effective for the operator and consumer by offering good quality in-depth service per air mile. An interesting account!

I hoped I might edit the date in the above as the time of this flight was early 1970’s (not 1960s). I stand corrected – I was still in school in the 60’s.

II agree with the above writer’s very astute statements.

On a personal note, I was an agent in Yellowknife in the 60’s, privileged to accompany Max on a beautiful May day, milk run, flight to Holman Island on a familiarization pass! As a young woman, it did not occur to me that it would one day be a somewhat historical day! As I recall, we made stops in Ft Resolute, Norman Wells (with a desperate runway where he needed to bank landing and taking off – with only about a quarter mile – to avoid the massive mountain & ice flows), Resolute Bay, Tuktoyuktuk.

Max showed me how to spot polar bears on the ice flows and would dip to lower altitudes for a closer look! We were greeted by the very gracious and energetic Inuit people, who looked forward to his arrival (weekly, I believe), and escorted to the main house for tea. I was struck by their height, which reached at best to my chest – I had some feelings of what Paul Bunyan may have had.

Max then left with several of the men to unload the supplies (including the beer keg), while I was surrounded by giggling, and industrious Innu women. They showed me around their crafts lodge and took time to help me choose several small items to purchase – very reasonably as I recall. Each time I stopped to admire their work, which was often, they would all stop what they were working on to prance around and admire it with me – applauding the creative woman responsible for the gorgeous item.

Soon it was time for the meal, which would consist of pork and beans, fresh from Max’s plane – a treat for the people – and my first taste of muktuk – not so bad! I was pleasantly surprised but have never had it again.

As we stepped out of the lodge, we were joined by the men, who were meandering over to where the sled dogs were tied on the ice flow – they had become separated by water and the ice around their ties had not yet melted. That would be a job later in the day, to go out and retrieve the dogs, if they weren’t freed by then. For the time being, several men tossed huge chunks of meat across to the dogs, who immediately quieted and got into the business of gorging themselves on the caribou.

Once inside the cozy house (which was actually more of a hut), which was crowded with furs, antlers, bones of different sizes, a wooden cook-stove and a huge table, we were offered very strong coffee, while the men enjoyed something a bit stronger.

It seemed we had only sat down and it was time to head back to Yellowknife with a couple of passengers and no freight. Everyone followed us to the twin otter and saw us off in grand style with giggles, waves and quite a lot of dancing around.

Glancing back we could see efforts beginning to kayak out and free the stranded dogs.

Max allowed me to take control of the plane for a few minutes and he landed us safely and very happily back into the Yellowknife sunset, around 10:30 PM.

Thanks for bringing that piece of documentary history back.

I am not in the slightest surprised that both CBC and CTV declined to broadcast it. It meets none of the required standards of either network, then and now, of fairness, balance, and accuracy.

Quite apart from a terrible lack of story focus the film makers made no attempt to balance Max Ward’s statements with comments from either of the two main airlines at the time, despite the fact that Ward and his executives were making constant references to them.

There was no outside comment, no analysis, and no context.

And the use of film clips from a Transport hearing, as well as a news conference, just drove a cinematic stake through the heart of the whole thing. What a boring technique to use endless stretches of talking head in front of a featureless background with no attempt at cover shots or B-roll.

What Max Ward achieved with Wardair was immensely important and although the airline was bought out his brief time in the airline industry changed that industry forever.

The film does a disservice to that story and stands as a terrible piece of documentary art and production far below the standards the NFB represents.

But let me end on a positive, and it is not a trivial positive. I remain greatly impressed by the quality of the audio recording and sound balance. Some of the locations, in particular the hangars and flightlines, are absolute horrors for sound engineers but the audio crew did an excellent job.