Tulku, Gesar Mukpo’s feature doc about young people being recognized as the reincarnation of great Tibetan Buddhist masters, is now available for download. This is great news because the film offers one of the most fascinating and unusual tales around and I personally think more people need to see it. (For more on NFB downloads, see this post.)

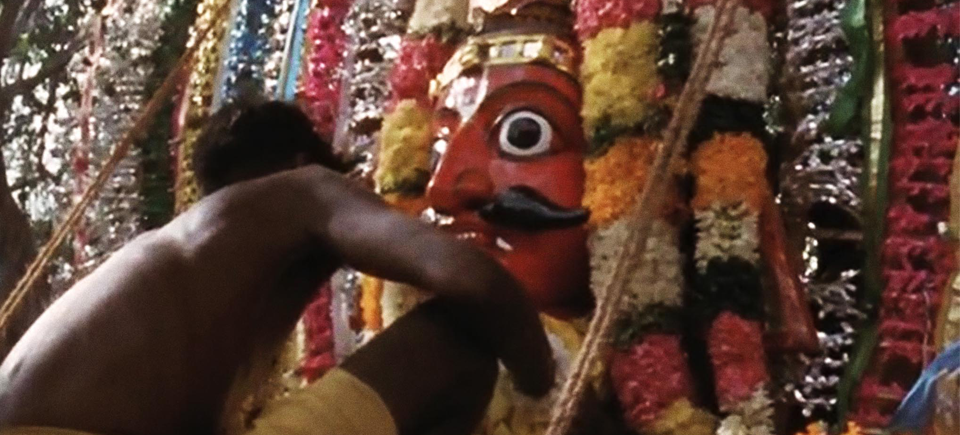

The story goes like this. Starting in the mid-1970s, Tibetan teachers began recognizing Western children as tulkus – the present-day reincarnation of a Buddhist master. Suddenly, a system that had ensured stable spiritual power and authority in Tibetan society for 800 years was transplanted into a completely different culture, i.e. ours.

Director Gesar Mukpo knows about this because he is one of them. When he was 3, he became one of the first people born in the West to be recognized as a tulku. For his entire life, he’s been trying to figure out what that actually means.

In Tulku, Gesar sets out to meet other tulkus to find out how they are making sense of this peculiar destiny. Traveling through Canada, the U.S., India and Nepal, he meets 4 other tulkus who struggle with the spiritual, social and personal implications of ‘tulku-hood’.

Regardless of where you stand on life after death, reincarnation, Buddhism, etc., this film is a fascinating inquiry into a largely uncharted zone of the where-does-religion-fit-in-the-modern-world question.

Check out the trailer below, and head to the digital boutique for a download of the film. (Starts from CAN $4.95)

For more on the film, here’s a re-run of an interview I did with Gesar Mukpo in August 2010. The filmmaker spoke to me on the phone from his home in Nova Scotia.

Carolyne Weldon: Where did this idea of turning your own story into a film come from?

Gesar Mukpo: There’s this program called Reel Diversity [Reel Diversity is an initiative of CBC Newsworld and the NFB to give emerging Canadian filmmakers of colour the opportunity to direct a feature documentary.] Well the first time I applied, I didn’t get it. So next time around, when the time came to apply again, I wasn’t sure what to pitch. The deadline was fast approaching. I wrote a paragraph, off the top of my head, about my own life. It took me 20 minutes. Afterwards, I looked at it and I thought, “Hey! That’s a pretty good story!” It was very spur of the moment. I had very little time to think of something. But it worked. The NFB loves personal narratives. Also, I would like to say I feel very fortunate to have obtained Reel Diversity’s mentorship and assistance. I heard it had been discontinued. It is a real shame it won’t be around anymore. So many talented filmmakers got their first film made through that program.

CW: Directing your own story meant being on screen. How comfortable are you with seeing yourself on film?

GM: (chuckles) When we started, I kept asking my producer: “Do I have to do it?” But if you set out to do it, you have to deal with it. There were lots of moments of hesitation. The story is very personal; it’s bound to feel embarrassing sometimes.

CW: How does it make you feel that you were chosen as a vehicle for rebirth by a great Buddhist master?

GM: Well first of all, the question is not whether this is real or not. It’s about how I dealt with it. The reality is that being recognized as a tulku had an impact on me. I try to understand the situation it created and continues to create.

CW: Do you know of any women tulkus. Did you interview some for your film?

GM: There are few in the West. In fact, there are very few female tulkus period. The Tibetan clergy is a very male clergy. But before and beyond gender, I was looking to let the story tell itself, for it to unfold naturally. Everyone featured in the film is related to me in some way – by either direct connection or karmic link.

CW: Other tulkus in your film discuss some of the darker aspects of the Tibetan clergy and tulku system, such as corruption. Do you fear alienating parts of your target (Buddhist) audience by voicing these?

GM: The film isn’t about taking sides. It isn’t about picking bones. It doesn’t strive to make a political argument. The idea was to take the system apart and go beyond it – from the systematic to the personal.

CW: How has the film been received so far?

GM: The film is being shown in festivals across Canada. It premiered in Vancouver last year, at DOXA. I think it’s the kind of movie that will have a much bigger life on DVD though, with the international audience and all that, as people review it on the internet. All in all, I feel like I achieved what I set out to do. I didn’t want it to be a “church” movie. I didn’t want to make a religious film, a Buddhist film or a political film. It’s a film about people growing up in peculiar circumstances. Something bigger and lighter than this “spiritual trip”. It’s still a relevant story, even if you don’t believe in reincarnation. Transformation of culture… dilution of culture, it’s everybody’s story.