“The Misery of Others”: The Ethics of Filming People on the Edge

“The Misery of Others”: The Ethics of Filming People on the Edge

* This is a guest post by Oisin Curran, web writer for the web doc Here At Home. More on this topic on the Here At Home blog.

In a recent post we talked about the ethical questions raised by the At Home study. It seems only fair that we now turn the lens on ourselves and ask some of the same questions.

As Toronto filmmaker, Manfred Becker says, “there are moral questions raised at every point in this project, including the filmmaking process. What’s my moral position making money off of people who live in such precarious situations?”

The NFB has a general policy of not offering compensation to the subjects of their documentaries. For Becker, this presents a serious dilemma: “During filming, the project manager might be there and the case manager might be there and the sound person and the camera person and the director… the only person who’s not getting paid is the participant. I think that’s wrong. I think it’s just not on that I make a living off the misery of others. I’m not assuming a “holier than thou” position but that’s how I feel and I want to live by that.”

Working or giving?

“One way of looking at this,” says Barbara Russell, who works and teaches in the field of bioethics, “is to consider what it is the participants are doing when they’re being filmed. Are they offering up their story as a gift? Or are they taking part in the work of advocating for the Housing First program? If the former, then perhaps some kind of financial return is neither expected nor needed. If the latter, then perhaps one could say that they are at work and therefore should be compensated in some way.”

“The idea of compensating participants is an age old subject in documentary,” says Michelle van Beusekom, Assistant Director General of the NFB’s English Program. “Some people think that money complicates the documentary filmmaking relationship….that if doc subjects are paid, then the motivation for participating becomes murky and what results can start to become performative rather than authentic. At the NFB our practice is not to pay a fee to participants although we do compensate if shooting with us means someone has to take time off work. We may cover meals, babysitting, transportation or other costs incurred as a result of the filming.”

And just to be clear, documentary filmmaking is rarely profitable. When Becker talks about making a living “off the misery of others,” he means that he’s collecting a salary for his work. Same thing for the cameraman and sound person he mentions in his example. As for the program manager and case manager he refers to, they too would be collecting their salaries, not profiting from the documentary. As van Beusekom points out, “Here At Home will never make money. It’s an online project available for free. Making this project is not a matter of creating a product to sell to the marketplace; it’s an exercise in using documentary storytelling to promote reflection and dialogue around a social crisis.”

Raw material

But as van Beusekom notes, compensation is only one of the ethical questions that documentary filmmakers have to deal with. “There are fundamental dilemmas about using people’s lives as the raw material for a film. For Here At Home, we did a lot of front end work with producers, directors, the commission. We consulted with an ethicist on informed consent, we developed a protocol for how the project is explained, talking through the implications of being in a film to make sure people are comfortable sharing their story. And there’s a rough cut screening for participants. We tried to provide as many opportunities as possible to make sure people are comfortable sharing their stories.”

In the past, the ethical hurdles involved in documentary filmmaking have been too much for Vancouver filmmaker Lynne Stopkewich, “It’s been a long time since I worked in documentary format largely because it’s very daunting and it’s a huge responsibility. You don’t know how the participants are going to feel about the finished film now or 5 years from now when their lives may be very different. I mostly work in dramatic film and TV and that’s very different because it’s all manufactured. With documentaries, these are real people that I’m representing but, at the same time, it’s still a representation and audiences may choose to interpret that representation in ways I never intended. So worrying about all that can be overwhelming. Film is powerful. But that said, when this project came up I jumped in with both feet because the material was so challenging and different and because this project is very collaborative – we’re collaborating with the participants.”

The courage to be visible

For her part, van Beusekom believes that the moral dilemmas posed by documentary filmmaking raise the question of why people participate in them in the first place. “Ideally people participate out of a desire to share. For some it can be deeply affirming to be listened to. Others may be motivated by the wish that one’s story might help someone else.”

This is exactly what drew Mark Wroblewski, to take part in the Here At Home film, Honestly Painful. He remembers the moment he decided to participate in the documentary project. “I saw [Olympic gold medallist] Clara Hughes talking on TV about her problems with depression and I said to myself, if she can do it, why can’t I? I thought, if I can help people by telling my story, then I should do it. Especially young people out there with problems of addiction and mental illness – they need to be given some hope that things can get better. And also, to be very honest, I like being in front of the camera. I’m a people-person and I like sharing.”

Paula Goering, At Home lead researcher, thinks that the Here At Home participants are offering us a gift by telling their stories on camera. “Many of the participants have been, in a sense, invisible for a long time. For them to be willing to share their experiences with the world in this way – it’s very brave.”

What about you? How would you react if you were asked to participate in a documentary. Would you be willing to tell the world your story on camera? Would you do it for free?

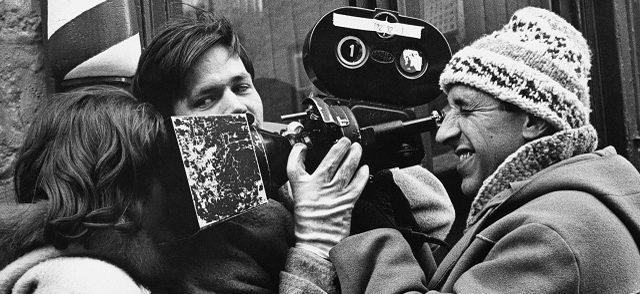

N.B. The photo at the top of the post is a production still from La Fleur de l’Age, a 1966 fiction film co-produced by the NFB. That’s the great Michel Brault getting very Cinéma Direct with a young Geneviève Bujold. The film has nothing whatsoever to do with the subject at hand; but the image was too good to resist.

You might be interested in this film and the discussion.

Love,

Judymom